Defense companies are already well involved in the world of industrial 3D printing. Just take a look at the latest America Makes project awardees to see some of their latest research. But many of them have been essential in fueling the tech almost since the beginning, with Lockheed Martin helping to cultivate Sciaky’s large-scale 3D printing technology, GE partnering with metal 3D printing firm Morris Technologies long before its eventual acquisition, and almost all of them using 3D printers for rapid prototyping. Raytheon is no stranger to the technology, previously using the technology to study warhead fragmentation in addition to prototyping parts. They even helped a team of University of Arizona students to launch their own rocket system. It should come as no surprise, then ,that the weapons manufacturer is considering the use of 3D printing to produce complete missiles.

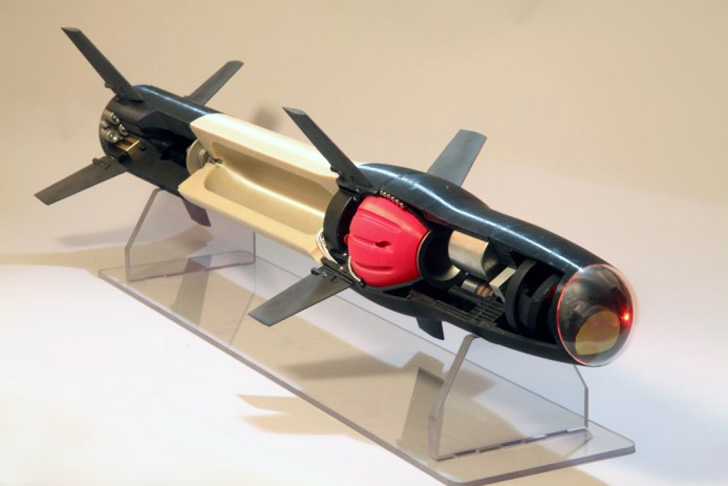

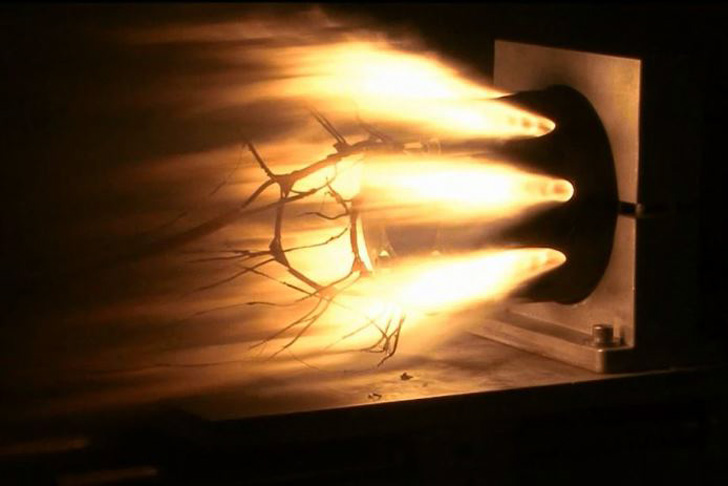

According to a post on the company’s website, Raytheon is in the process of increasing the use of 3D printing extensively and their Missile Systems division has already 3D printed almost every part of a guided weapon, including rocket engines, guidance and control systems components, fins, and more. They are now proceeding to look at the possibility of 3D printing conductive circuits (Voxel8, anyone?), as well as housings for their gallium nitride transmitters and fins for guided artillery shells. Not only would 3D printing help reduce costs, by eliminating the need to machine parts, but it might help them print missile components in the field of war. Raytheon engineer Jeremy Danforth has successfully printed working rocket motors and says, “You could potentially have these in the field. Machines making machines. The user could [print on demand]. That’s the vision.”

Naturally, the technology also enables the ability to 3D print intricate designs. Another engineer, Travis Mayberry, explains that this opens up new possibilities for modifying the thermal capabilities of a part, “You can design internal features that might be impossible to machine. We’re trying new designs for thermal improvements and lightweight structures, things we couldn’t achieve with any other manufacturing method.”

To help drive the improvement in 3D printing technology, Raytheon is also a part of the USA’s pioneer 3D printing institute, America Makes, where Raytheon materials expert, Dr. Teresa Clement, serves as the chair of the executive committee. In the latest round of awards from the institute, Raytheon stands to benefit directly from at least two projects meant to streamline both the design and printing processes. Dr. Clement says, “Ensuring consistent production integrity will be part of the next steps to realize this vision.”

Further to that point, Leah Hull, who manages the company’s 3D printing, describes how the technology improves the supply chain. “When we print something, we have fewer piece parts, so your supply chain becomes simpler,” she says, “Your development cycles are shorter; you’re getting parts much faster. You can get a lot more complex with your design because [you can design] angles you can’t machine into metal.”

But their research into 3D printing isn’t limited to improving the process itself. The company wants to push the technology into new directions via their use of academia at U Mass. The Raytheon University of Massachusetts Lowell Research Institute (RURI) is currently working to 3D print circuits and microwave components, which could be used to improve their Patriot missile systems, previously implemented somewhat unsuccessfully in the first Gulf War. This would not only lower costs, by reducing material waste, but also allow for more complex geometries with high-resolution and high-performance silicon.

Raytheon’s director for the institute, Chris McCarroll explains, “The word ‘printing’ implies lower cost. It’s additive manufacturing. When we make integrated circuits [now], it’s all subtractive. We put down very expensive materials and wash away everything we don’t need.” He continues, “There’s currently a hierarchy in our manufacturing. We make the structures, the housings, the circuit cards, with the right materials, and then we integrate them into a system. What we see in the near future is printing the electronics and printing the structures, but still integrating. Eventually, we want to print everything together. An integrated system.”

McCarroll says that Raytheon’s institute at U Mass has made progress in printing conductors and dielectrics, as well as carbon nanotubes for printing future missiles. Though he suggests that that would be a long-term goal, he believes that there is still a lot of work yet to be done before weapons will be instantly produced in armed conflict, “Before a warfighter can print a missile in the field, you need quality, controlled processes to fabricate all the component materials: the metallic strongbacks, and the plastic connectors, the semiconductors for processors, and the energetics and propulsion systems. The hard part is then making the connections between these components, as an example, the integrated control circuit that receives the command to light the fuse. At some relatively near-term point you may have to place chips down and interconnect them with printing. Or, in the future, maybe you’ll just print them.”

But engineer Jeremy Danfoth says that they’ve made significant progress in printing parts that would account for nearly a complete missile, “We are printing demos of many of the seeker components. And we demonstrated a printed rocket motor. We’ve already printed 80 percent of what would go into a missile.” So, when will the day come that such weapons will be printed by military manufacturers? Well, Danforth says, “There are folks in industry printing warheads.”