There is a constant to mass that is difficult to acknowledge when considering the personal. With most physics concepts, the proofs are understood in the realm of the abstract, and if it is true that matter in a closed system is never lost, merely altered, maybe artist Lee Wagstaff’s 3D printed skull will help materialize the idea. As an artist known for dissolving boundaries between private and public, Wagstaff will create a unique 3DP sculpture that dissolves one being and forms a new. He has taken the axiom concerning an artist’s awakening as only occurring when we “kill our fathers” to another level. The artist will crush the skull of his father and use the powder as filament to form a model of his own skull. In essence, the father will dissipate and manifest the son who could not exist without the father, but could not take form while the father’s form remained intact.

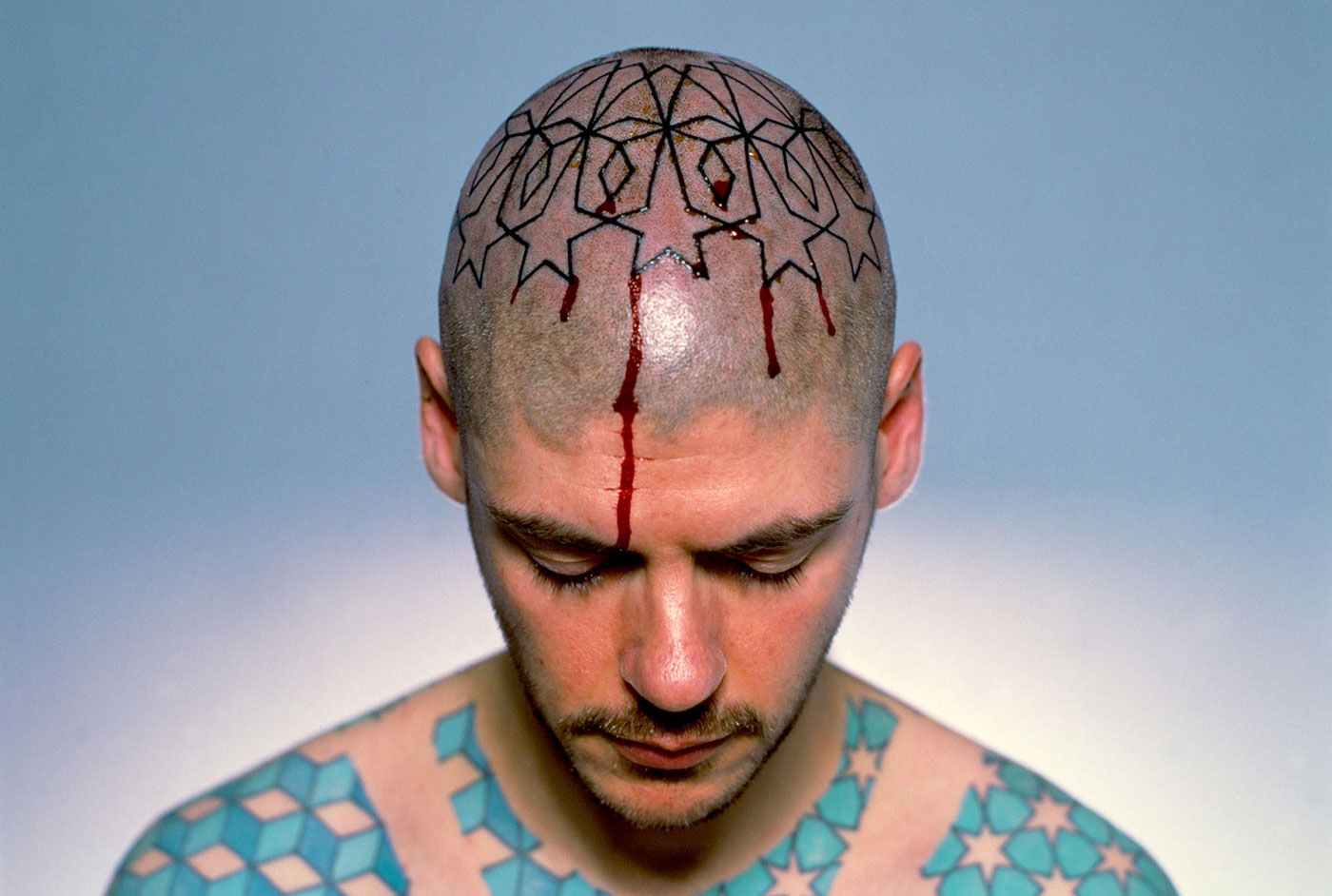

Born in London, the 45 year-old artist studied at Central Saint Martins and the Royal College of Art before establishing his international exhibitions, including the controversial and intriguing works “Shroud” and “100 Nights of Solitude”. Both involved personal markings of t-shirts, the former with blood, the latter with ejaculate. His own body is marked with copious tattoos, which often feature in his work. In fact, he plans to engrave the 3D printed skull with replicas of his own head tattoos.

Estranged from his father, Wagstaff revealed to Vice.com the purpose of the project. He hopes to explore their “difficult” and “weird” relationship as a vehicle to address the concept of transference and religion. “I immediately thought about how you could replace the powders you’d use for a typical 3D print,” he told Vice. “For me, bodily materials are the same as other art materials, like ink, or paint, or plaster.”

With a skull, the form defines an individual, the existence of a life no longer alive. Does the destruction of the skull mean in some way the destruction of that former identity? It certainly proves the law of the conservation of mass, the transfer of matter from one form to another with nothing supposedly lost. In a way, the powder turned filament turned to new skull holds the essence of the former in a return to the familiar form of a skull, yet it is new.

The act performed by Wagstaff mimics the transfer occurring infinitely in nature, infinitely in our own bodies like one cell splitting into two. It holds the old, the former, yet can never return to its previous state, the act is irreversible, irrevocable. Inevitable loss breeds the promise of new life, of new form. We ask as Hamlet with York’s skull in hand provoked, “Why, e’en so: and now my Lady Worm’s; chapless, and knocked about the mazzard with a sexton’s spade: here’s fine revolution, an we had the trick to see’t. Did these bones cost no more the breeding, but to play at loggats with ‘em? Mine ache to think on’t.”