A couple of studies have so far been performed to determine the potential dangers of 3D printing plastic, both involving the inhalation of particles of ABS and PLA. Researchers at the University of California, Riverside have added to the research, getting into the toxicity of the material on actual organic cells, using zebrafish embryos.

When graduate student Shirin Mesbah Oskui began studying zebrafish embryos with a 3D printer in UC assistant professor William Grover’s lab, she saw that the embryos were dying off at rapid rates when exposed to 3D printed parts, leading her and Grover to studying the potential toxicity of 3D printed parts. Examining parts made from FDM with a Stratasys Dimension Elite 3D printer and parts made from photopolymer resins, using a Form1+ SLA system from Formlabs, the UC Riverside team studied the survival rates of zebrafish embryos.

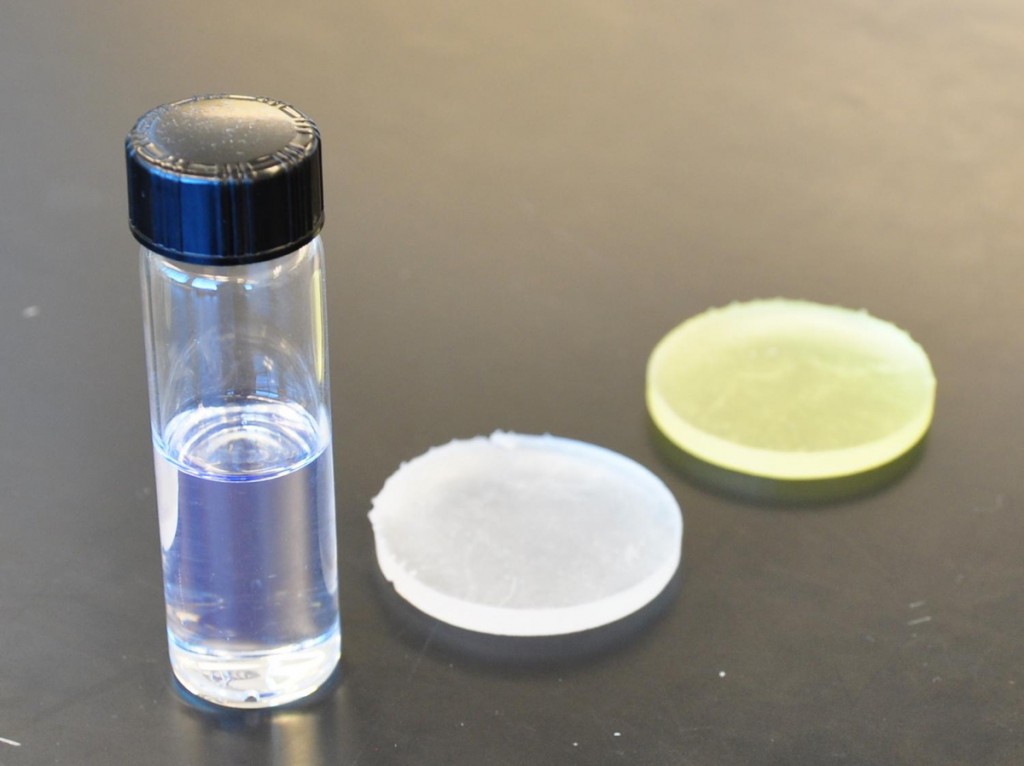

The team created disc-shaped components, one inch in diameter, which were then placed into petri dishes the embryos. In both cases, they saw decreased survival rates of embryos exposed to 3D printed parts than those in the control group. I can’t access the article, published in Environmental Science & Technology Letters because, as important as it is to know the dangers of printed plastic, it’s more important to charge people for information.

What has been made publicly available is that FDM embryos had a “slightly decreased” survival rate compared to controls, but that more than half of the SLA embryos were dead by day three and all were dead by day seven. Additionally, all 100% of the embryos that hatched, which were few, had developmental abnormalities. Post-processing of SLA parts with UV light, which can be required for SLA prints regardless, was shown to decrease the toxicity when pats were exposed for one hour, something that UC Riverside has filed a patent for, but that 3D Systems already has a patent for.

The research could raise issues related to regulating 3D printing technology, through the Toxic Substances Control Act administered by the EPA. The materials used in 3D printing are already regulated by the EPA, like ABS and plastic resins, and most companies seeking legitimacy provide the safety data sheets for their materials, without revealing the exact proprietary make up of their substances. For this reason, I believe that the only new contribution this line of research could make is about the reaction between UV light and photopolymers or a heating element and plastic filament because the toxicity of ABS and many photopolymers is already known.

I’m always one for regulation, specifically when it comes to hazardous materials, and I’m also one for warning labels so that consumers can make informed decisions when messing around with the stuff. Here, however, I don’t think that 3D printer manufacturers and material suppliers should have to go to extra lengths when compared to those producing chemicals for use outside of 3D printing simply because it’s a hyped technology. This is the same way I feel about 3D printed guns, in which the hyped topic is used to invent some new form of regulation, when, really the same regulation could be applied to all gun manufacturing.

In other words, I personally believe that Formlabs and Stratasys, as well as every business dealing with hazardous chemicals, should have to apply warning labels to their products and that the EPA should regulate their products, but that so should every other company using toxic chemicals on a regular basis. In the United States, chemical products are subject to an innocent until proven guilty policy, in which these goods can be released into the market and will only be removed if sufficient evidence is supplied, by third parties unrelated to the manufacturers of those goods, to force their removal.

Unfortunately, there aren’t many powerful enough to conduct the necessary research to get them taken off of shelves, including the EPA which is overburdened, underfunded, and not sufficiently empowered. As a result, Johnson & Johnson No Tears Baby Shampoo was sold with formaldehyde (you know, for preserving dead bodies?) and 1,4-dioxane until LAST YEAR, when it finally revised its formula in response to demands from consumer and environmental advocacy groups. Even more depressing is the fact that the US was one of the few developed countries where selling this product was allowed, as not other developed nations, like those in the EU, prevented Johnson & Johnson to sell the stuff and forced them to sell a safer formula in their countries.

We’re living in a post-industrial revolution era, in which the pollution and toxicity of revolutionary new manufacturing processes is being discovered on a regular basis, so it makes sense to change the way we make things and what we make them out of. To go back and find all of the toxic chemicals that made it onto the market during previous eras of lax regulation, the EU has implemented their REACH policy, in which they slowly test each product being sold on the market for potential negative effects and force the removal of any that don’t comply. It won’t be until the US enacts similar regulations that our products will be somewhat safe. Until then, if you’re in the US, you can trust that your filament, resin, and pretty much everything around you is potentially dangerous because there’s no regulation to tell you otherwise.