A new 3D printing method from the Langer Lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has developed a way of making vaccines that releases multiple doses of a drug over a controlled period of time.

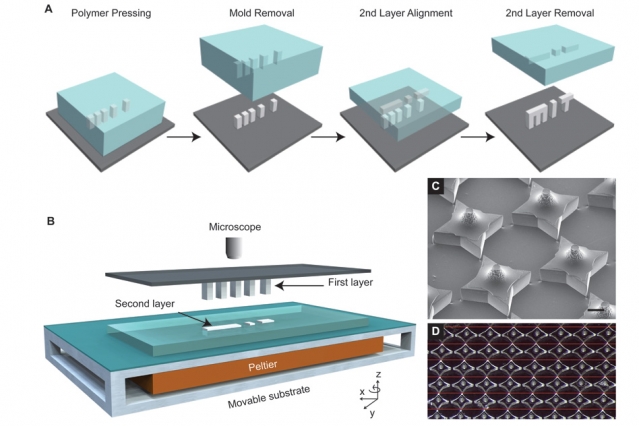

Termed StampEd Assembly of polymer Layers (SEAL), the process harnesses photolithography to 3D print and seal microscopic wells, or “cups”, containing acute doses of selected liquid drugs.

The technique has the potential to transform the vaccination for children and those most in need around the world, presenting “unprecedented opportunities” manufacturing for medicine and more.

Animation of MIT’s SEAL process. Clip via Science Magazine Supplementary Materials.

Medical solutions for those in need

The research is supported by funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation that aims to solve “global health and development problems for those most in need.”

Project lead Robert Langer explains the concept saying “…people could potentially receive a single injection that, in effect, would have multiple boosters already built into it.”

Langer adds, “This could have a significant impact on patients everywhere, especially in the developing world where patient compliance is particularly poor.”

Another 3D printing project to funded by the foundation is the development of a new contraceptive paradigm that uses Aether 3D bioprinters to create Fallopian tube models.

Every cup has a lid

MIT’s SEAL method uses photolithographic 3D printing to cure silicon molds of microscopic square cups and lids. Under 400 mm in size, a total of 2,000 molds can fit onto a single glass slide.

The method differs from other nanolithographic methods of 3D printing as it doesn’t require the use of a photoactived additives that are largely harmful to humans.

The SEAL 3D printed molds are used to shape structures from FDA approved PLGA – a copolymer that is biocompatible, degradable and used for controlled drug delivery in cancer treatment and post brain surgery.

Each cup is filled with a liquid drug by an automated dispensing system. Afterwards, the lids are added and heated slightly to fuse together.

Over one month of controlled drug delivery

In the Langer Lab study, the micromolded particles (cups) are tested in-vitro, and added to a syringe for administering in-vivo to living animal models. Of three different PLGA samples tested, one sample in particular proved capable of gradual drug release over a period of 56 days. Whereas others released over 20 and 30.

An exciting discovery

A report on the SEAL process was published in September’s Science magazine.

The paper is co-authored by Allison Linehan, David Yang, Adam Behrens, Sviatlana Rose, Zachary Tochka, Stephanie Tzeng, James Norman, Aaron Anselmo, Xian Xu, Stephanie Tomasic, Matthew Taylor, Jennifer Lu, and Rohiverth Guarecuco.

In closing comments on the technique Langer says, “We are very excited about this work because, for the first time, we can create a library of tiny, encased vaccine particles, each programmed to release at a precise, predictable time”.

He adds, “The SEAL technique could provide a new platform that can create nearly any tiny, fillable object with nearly any material, which could provide unprecedented opportunities in manufacturing in medicine and other areas.”

For 3D printing research, news and more sign up to our free newsletter and find us on Facebook/Twitter.

Check out 3D printing events near you here.

Featured image shows an MIT logo 3D printed by the new photolithographic method developed by the Langer Lab. SEM image via the Langer Lab/MIT.