Sascha Dickel and Jan-Felix Schrape are two of the contributors for a collaboration of writing on 3D printing collected in The Decentralized and Networked Future of Value Creation. The collection, edited by Jan-Peter Ferdinand, Ulrich Petschow and Sascha Dickel aims to grasp the current rise of 3D printing and discuss the technology’s impact on the future of value creation. This article is part of a series where we will focus on each chapter of the book. Let’s have a look!

Materializing Digital Futures

The contribution is penned by Sascha Dickel and Jan-Felix Schrape, and explores the idea of content creation on the internet paving the way for 3D printing.

“Based on two paradigmatic case studies—Web 2.0 and 3D printing— this chapter explores the semantic patterns of popular media utopias and unfolds the thesis that their continuing success is based on their multireferencial connectability and compatibility to a broad variety of sociocultural and socioeconomical discourses. Further, we discuss the ambivalences and social functions of utopian concepts in the digital realm.”

This article shows that with the case of 3D printing, already existing expectations surrounding the Web 2.0 are being updated. The expectations in question relate to the idea of the roles of producer and consumer, and the fusion of the two (prosumers). Dickel and Schrape also suggest that the continued success of media-utopian ideas is based on their ease of integration into a number of area-specific and fundamental societal discourses as well as on their instantaneous compatibility with a number of social references. And finally they talk about the nature of the utopias, and how they shouldn’t be seen as predictions for future developments, but viewed as social narratives that provide a starting point concerning the uncertainties and difficulties in shaping current social communication.

So let’s break that down a bit.

The beginnings of the Prosumer and its transition to 3D printing

The term prosumer derives itself from the roles of producers and consumers.

“As “prosumers”, individuals are expected to transcend the boundaries of the production and consumption sphere, overcome associated role descriptions and serve as a counterweight to the centralisation of production in many sectors of the economy.”

Dickel and Schrape theorise that the utopias built around “Web 2.0”, a synonym for a second wave of Internet optimism in the mid 2000’s, and 3D printing strive to convince their audience that new technologies will transform our society into one of prosumers. This is characterised by a “democratisation of social decision-making processes, a decentralisation of the production and distribution of media content and material goods, and an emancipation of once passive media users, consumers, and citizens.”

By holding onto the idea of the adaptable era of the prosumer, they can orient themselves directly on “social reality”, and have real world impact unlike previous “media utopias”. The underlying problem with media utopias is that they only really existed to change superficial aspects of society as they had no materiality. In the early days of the internet, “cyberspace” was interpreted as a different realm, “detached from capitalistic constraints and political power structures”. The concept of the internet being an online shelter became weaker when it was adopted into mainstream society;

“Media utopias today no longer focus on the idea of cyberspace as an independent and progressive niche, but instead foresee an online-induced transformation of the society as a whole. Indeed, online technologies have become not only a significant economic factor, but also a central aspect of everyday life. Thus, it is not surprising that leading news providers regularly offer media-induced visions of a nearby future and that these expectation horizons are constantly expanding. This is true for the Web as a traditional media technology, but also and especially for 3D printing, which has most clearly freed the modern media utopia from its stigma of immateriality.”

Dickel and Schrape then talk about the rise of Web 2.0 and its impact on “commons-based peer production” as voluntary and self-directed “collaboration among large groups of individuals without relying on either market pricing or managerial hierarchies to coordinate their common enterprise”. This created an immaterial precursor for 3D printing to become the real world counter part.

Kevin Kelly, founder of the Wired magazine first applied the term prosumer to “the new web” in 2005, when he characterised Web 2.0 as “the […] most surprising event on the planet” and accused the technology experts of his time of underestimating the disruptive force of online technologies. He predicted that the classic consumer by 2015 would be a relic of the past:

“[…] in the near future, everyone alive will (on average) write a song, author a book, make a video, craft a weblog, and code a program. […] What happens when everyone is uploading far more than they download? […] Who will be a consumer? No one. […] The producers are the audience, the act of making is the act of watching, and every link is both a point of departure and a destination”

The dissolution of well-established social roles of consumer and producer ultimately led to an acceptance of the idea of a technologically driven democratisation of the production and distribution of consumer and media goods.

Prosumers in a physical space

Dickel and Schrape go on to talk about the importance of open source 3D printing projects like RepRap and Fab Labs in the widespread adoption of material prosumers.

With Web 2.0 paving the way for immaterial creation and consumption housing itself in the same individual, 3D printing has allowed consumers to become material manufacturers in their own homes.

“Much as with the visions surrounding Web 2.0, future concepts of 3D printing can be seen as a renaissance of utopian beliefs and ideas that were first articulated decades ago but lacked a technological foundation that would have provided them with sufficient plausibility.”

The authors then talk about the importance of RepRap, an open-source development project created by Adrian Boyer with the goal of producing 3D printers assembled largely from parts that in turn could be produced by 3D printers. His intention for the technology is to break up capitalist economic structures: “If each of us only had a 3D printer by which we could produce many everyday objects ourselves, the need to purchase products would lessen.”

The rise of Fab Labs in 2005 from MIT also contributed to the notion that anyone could create anything, regardless of gender, age, origin or status. The ease of which this technology can now be accessed means that more and more people are becoming prosumers in the physical sense.

Established manufacturers are integrating digital production technologies to supplement their pre-existing methods in order to meet a rising industry demand.

“The “next industrial revolution,” in which an emancipation of the prosumer in the area of material production will merge the utopias of Web 2.0 has not yet happened. Now that the hype of 3D printing appears to have reached its peak, the realisation of a dedifferentiated “prosumer society” seems once more to be only a distant prospect. This is increasingly acknowledged in academic circles, where only recently “shared machine shops” were still being positioned as a force to transform society. “Despite the marketing clangor of the ‘maker movement’, shared machine shops are currently ‘fringe phenomena’ since they play a minor role in the production of wealth, knowledge, political consensus and the social organisation of life”

It’s an interesting section with some intriguing ideas.

Architectures of digital futures: complexity reduction

The start of this section points out that it is safe to assume that the media technologies of Web 2.0 and 3D printing will not be the last to employ the concepts of decentralisation, democratisation and emancipation. Dickel and Schrape then go on to explain different forms of utopian communication as it relates to new media technologies.

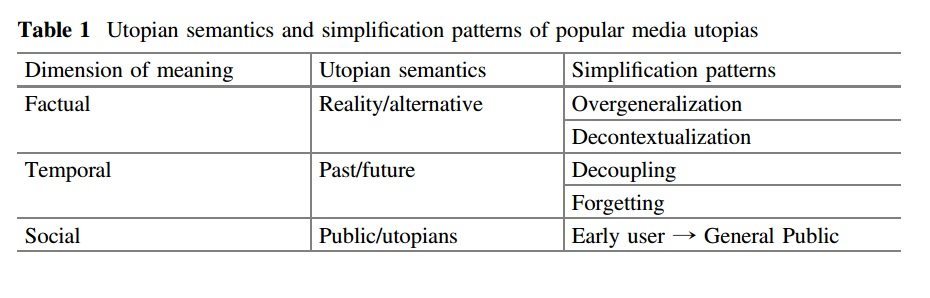

“These visions are not primarily technical roadmaps awaiting realisation, but rather an expression of a type of public communication that perpetuates the fundamental semantic structures of modern utopianism under the banner of new media technologies. Drawing on the dimensions of meaning in social communication, these structures can be characterised as follows:

Factual dimension—Utopias consider a given situation in the light of possible alternatives; as result, observed reality first is subjected to an explicit or implicit critique and secondly depicted as contingent and modifiable. Each respective reality is compared to an envisioned alternative viewed as being an improvement on the status quo.

Temporal dimension—The difference between critique and alternative is carried over to the temporal difference between past and future, with the present represented as a transitional turning point in which existing structures can be overcome in order to realise the alternative possibilities of the future.

Social dimension—In their appeal for the realisation of future possibilities, utopians position themselves as visionary speakers addressing a public implicitly or explicitly alleged to be trapped in a mindset that views the “here and now” as being without any alternative.”

They point out that in contrast to social utopias, most media utopias believe that behavioural changes or new political orders are not enough to bring radical social change. They believe that new media technologies are needed as conduits for bringing about a real transition. Each new technology serves as a stepping stone to more universal hopes for the future.

The universal compatibility of media utopias is also touched upon in this section, raising questions on how successful they can be in different areas. Wikipedia is raised as an example, stating how successful and effective it is as an application for user-centred knowledge production, but how that concept can be difficult to transfer to other fields, such as the production of daily news reports (WikiNews is not such a success). Secondly, Dickel and Shrape talk about the idea of new media becoming disconnected from what came before it, before moving onto the problems of the behaviour and usage preferences of early users of new technology.

“As a result, these fundamental semantic structures and simplification patterns (Table 1) give rise to highly distinctive narratives of a near future whose origins are already inherent in our present. As seizable discursive points of reference among early users, they facilitate differentiation from other social groups, contribute to the motivation and coordination of the mostly young and well-educated early users and participants, and supply a readily utilised basis for legitimisation in decision-making processes (e.g., in political or economic contexts). Social sciences, in many cases, also gratefully make use of media-utopian ideas, as such references to popular visions and narratives do not only lead to an easier acquisition of research funds; they also offer the opportunity of revitalise long-cherished normative ideals—for example, the hope for a fundamental societal democratisation or the dissolution of power asymmetries.”

Dickel and Shrape point out that the dissolution between the usual roles of consumers and producers have both a negative and positive impact. On one hand, they lack the expertise of qualified professionals, but at the same time they bring about a new way of thinking.

“Media utopias thus can be regarded as productive types of communication. They serve to direct a specific technological innovation into a new context or along an unconventional path of development. They generate attention for respective potentials of certain technologies, provoke the need for follow-up communication, and thus channel the discourse in a particular direction—and for this reason, they are constantly being reformulated.”

The technopolitics of digital futures: putting utopias into context

“In the visions outlined, technology is assigned a prominent role as it promises control over space and matter. Through technology, society conceives itself as the creator of its own future.”

Dickel and Schrape talk about positioning technology as an open object, and goes on to explain that the idea of the open object refers to network-like technological devices designed for never ending connectivity, extension, and modification. The openness of such objects is expedited by the separation of hardware and software, like smartphones for example. In the course of digitisation, we as a society are being inundated with open technical objects and their (more or less well-functioning) interfaces. “The heart of media utopias is the conception of new interfaces between technology and society—as based on current and foreseeable processes of technological mechanisation.”

They raise the notion that the media utopias surrounding the Web 2.0 and 3D printing hold out the prospect of a technologically mediated decentralisation and democratisation of social relationships and an emancipation of previously passive media users and consumers.

“The apparent “neutrality” of technology supports the conformability of technocentric visions to already existing social narratives and role models. Thus, the utopias outlined here are able to tap into hopes for (political) democratisation, (individual) emancipation, (economic) decentralisation, and (environmental) transformation.”

They finish their entry in the book by talking about the discord that arses by everyone becoming both producer and consumer. Amateurs are raised to the level of professional.

“In order to go beyond the analytic capacities of genuine utopian discourses, however, an understanding of long-term social transformation processes and a socio-structural contextualisation becomes indispensable. The omnipresent prosumers in media utopias, for instance, can be described as holders of “secondary performance roles”, selectively rendering contributions and services that were previously reserved to specific professions or members of professional organisations. Active media users (e.g., bloggers, makers) clearly differ from passive consumers; at the same time, they can be differentiated from professionals in primary performance roles (e.g., journalists, industrial manufacturers), as their voluntary efforts are not tied to an organisational setting and they usually are motivated by short-term incentives or personal interests.”

The entire piece takes an interesting look at how the introduction of widespread internet use allowed users to create their own content, whether it be blogs, music, films, etc. The consumers turn into producers, and the addition of 3D printing allows us to bring that into a more physical world. The ability to create tangible objects with our own machines is an amazing innovation, and could lead to the next industrial revolution.

Dickel and Shrape have delved into thought provoking ideas, saying that the present roles of consumer and producer are in place purely through our own societal structures, and that the merging of the two will help us all shape our own futures.