The ongoing conflict taking place in the Middle East between Israel and Palestine is among the most distressing in modern history. In addition to regular civilian causalities and the widespread destruction of homes and infrastructure, rendering the water undrinkable and making electricity a rare commodity, the siege of Gaza and maintains a blockade that prevents basic goods from entering the area. Until the humanitarian crisis is resolved, the people of Gaza have been forced to find new methods for bringing in such supplies as food, water, and medical items. In this last category, one doctor based in the area, named Tarek Loubani, has turned to 3D printing to create low-cost medical devices to help his Gazan patients. Among these devices is a $0.30 cent stethoscope that works better than its traditionally-manufactured, $200 equivalent.

Loubani launched the Gila project in 2012, after the destruction of numerous public and NGO buildings, resulting in civilian deaths and injuries, brought the doctor in contact with numerous Gazan patients, but without the necessary medical supplies to treat them. According to The Register, Loubani told the Chaos Communications Camp in Zehdenick, Germany, “I had to hold my ear to the chests of victims because there were no good stethoscopes, and that was a tragedy, a travesty, and unacceptable.” At one Gazan hospital, taking care of more than a million patients, Loubani suggests that there was only one otoscope, for examining ears, and several stethoscopes.

Loubani continues, “We made a list of these things that if I could bring them into Gaza, into the third world in which I work and live, then I felt like I could change the lives of my patients. I wanted the people I work with to take it, and to print it, and to improve it because I knew all I wanted to do was bring the idea.” The result was the Gila project.

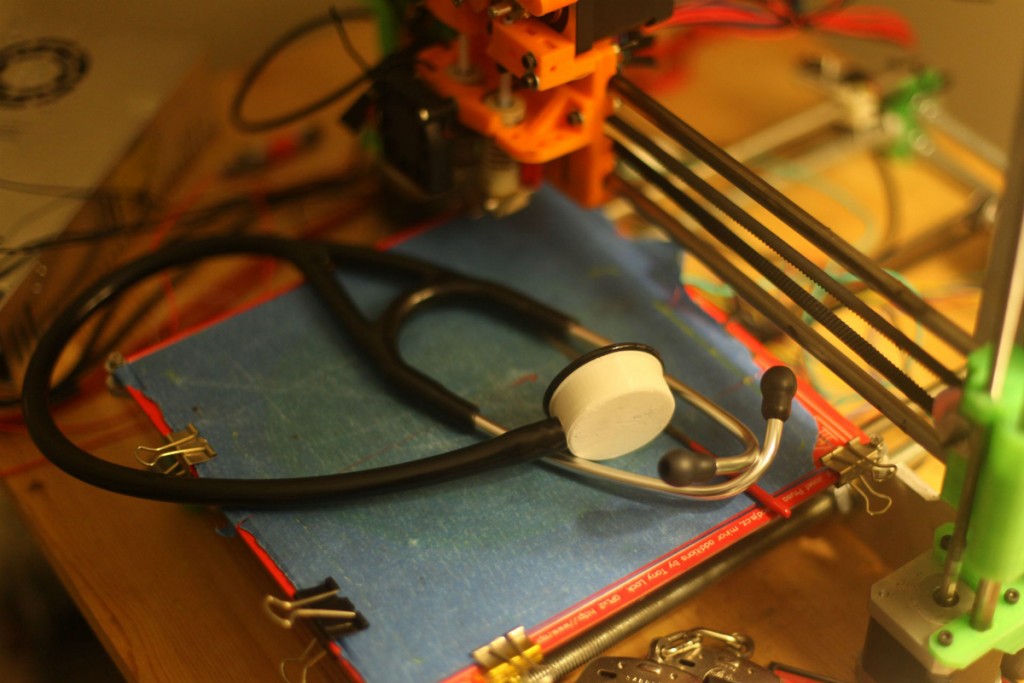

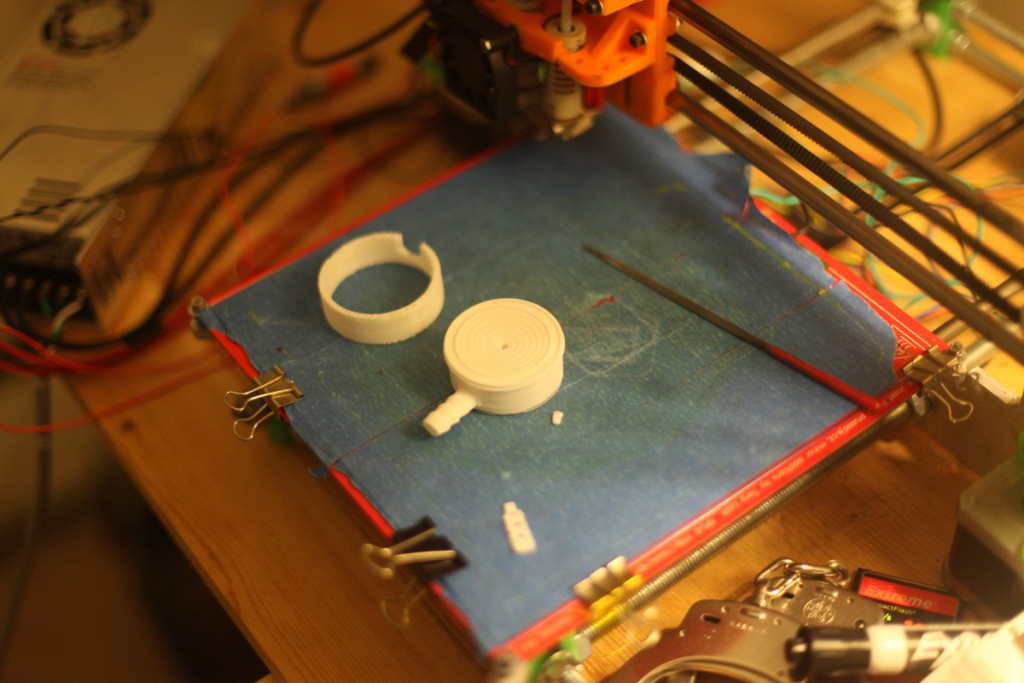

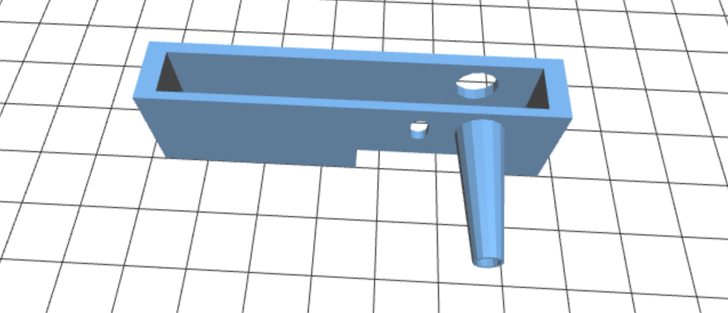

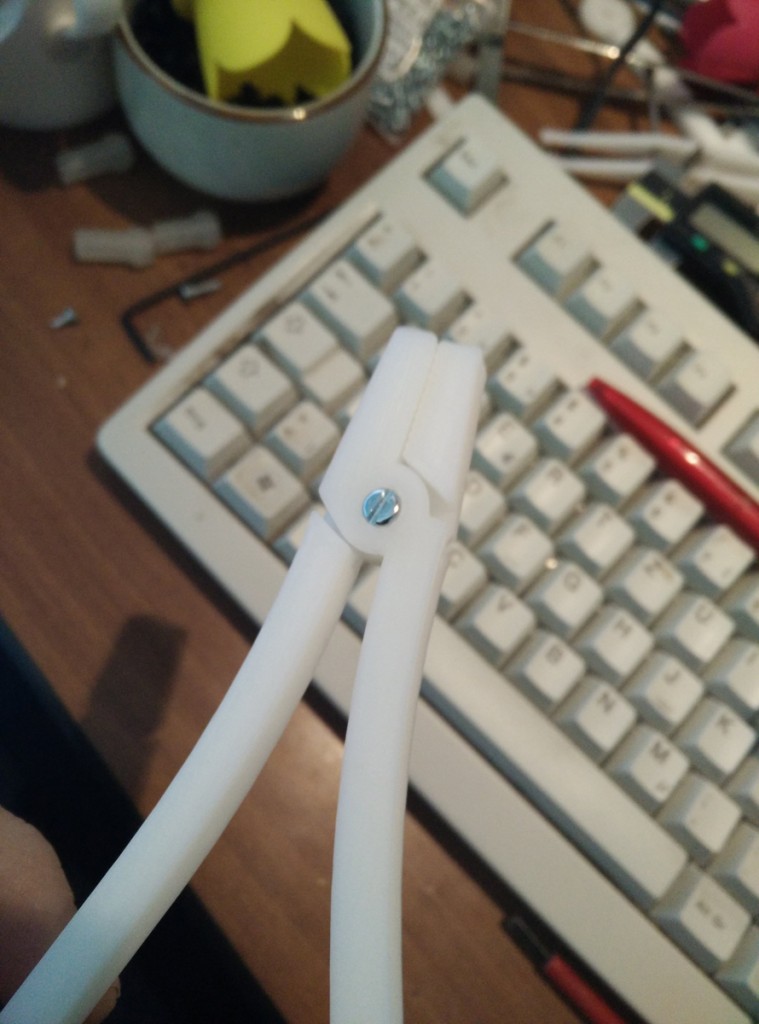

With the Gila project, then, the doctor began designing devices essential in the field, but that could be made at a fraction of the cost. On Github, he has posted a number of open source designs, including a small loom for weaving gauze, an otoscope, 3D printable surgical tools, and a stethoscope that Loubani and his team have demonstrated to work better than the global standard version currently on the market, the Littmann Cardiology 3. Using audio-frequency response curve tests, the team show that their 3D printable device, which can be printed for about $0.30 in material, has even better sound quality than the $200 Littmann device. The rest of the parts needed, however, could cost a bit more, but they are trying to bring those costs down to $4-6. These parts include: “20cm UPVC 6mm OD, 4mm ID; silicone for ear plugs; diaphragm: cut from a report cover with approx 0.35mm plastic sheet, we used a Staples 21639 (UPC 718103160223); and silicone / rubber ring for diaphram mount.”

The makeshift stethoscope wasn’t cheap to produce, though. Working with a team of experts and hackers, the R&D costs to create it total somewhere around $10,000, including the construction of the low-cost RepRap Prusa i3. The stethoscope designs, however, are now free to the world. And Loubani is confident that it works, saying, “This stethoscope is as good as any stethoscope out there in the world and we have the data to prove it.” As Loubani and the Gila project seek independent reviewers to build and use the device, the doctor believes that the peer-review process will be a “cake walk”. The hard part will be developing more advanced equipment.

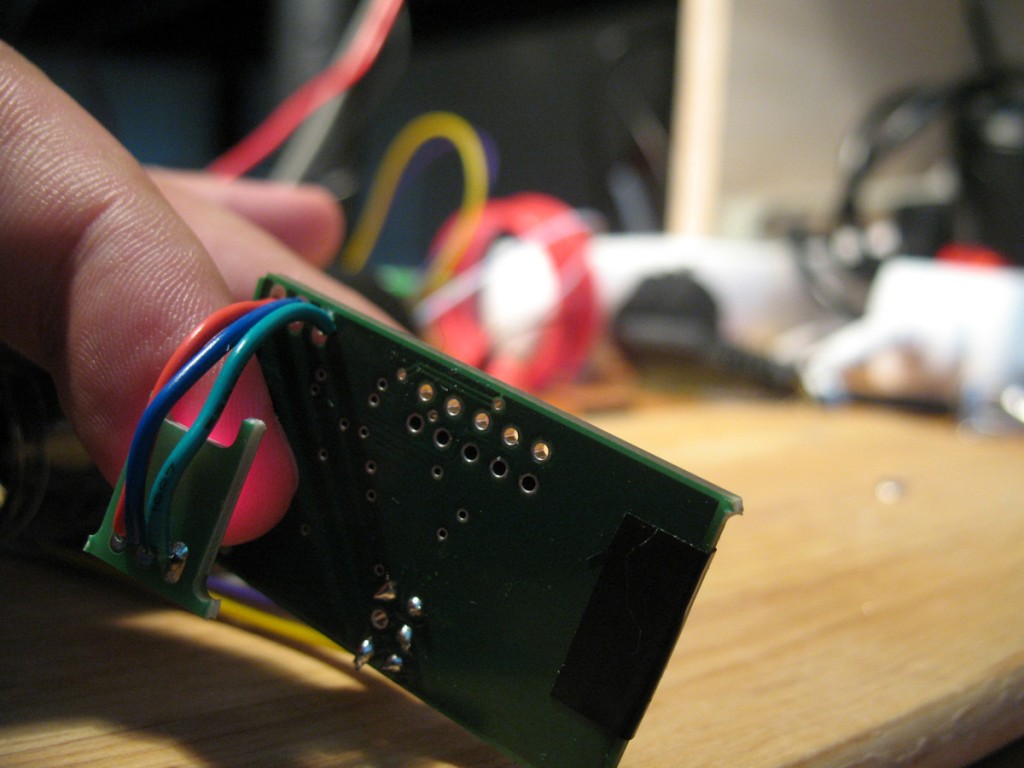

Next, the Gila project is working on a 3D printable pulse oximeter, for monitoring oxygen in the blood, which they believe is in the final stages of development. Dr. Loubani tells Wired, “The technology in the Pulse Ox is trivially simple for anybody with a high school-level knowledge of electronics: print, screen, etch, solder, test. I learned to assemble a pulse oximeter in an afternoon, and I could teach you to do the same even if you’ve never soldered before. The main challenges to all of these are making devices that work, and providing scientifically proven ways to test and validate the devices.”

Even more impressive, they’re tackling an electrocardiogram and even a haemodialysis machines. According to the doctor, these are the three most expensive, but essential medical devices for saving lives in the field. And, in a separate project called EmpowerGAZA, funded on Indiegogo, the doctor is hoping to bring self-sustainable, solar energy to Gaza that can keep hospitals up and running, despite any attacks. Of EmpowerGAZA, Loubani says to Wired, “The United Nations Development Programme is now coordinating with the various stakeholders to ensure a successful deployment. The next step is to engineer the system that will be used; then to request permission from the Israelis to import solar panels and batteries (both are currently banned); then to bring in the materials; then to build out; then to test.”

Despite the blocking of humanitarian flotillas as recently as this past June, the doctor hopes to be able to get the materials into the under siege region. While EmpowerGAZA could become a testament to what sustainable energy can mean for third world countries, the Gila project is a symbol of the possibilities for low-cost medical equipment. If powerful nations and medical manufacturers throw their weight behind both endeavors, Loubani’s work could spread to countries in need the world over.