BOFA International, a developer of fume and particle extraction technology, has published a research paper reviewing the impact of particulates and gases emitted by 3D printing processes.

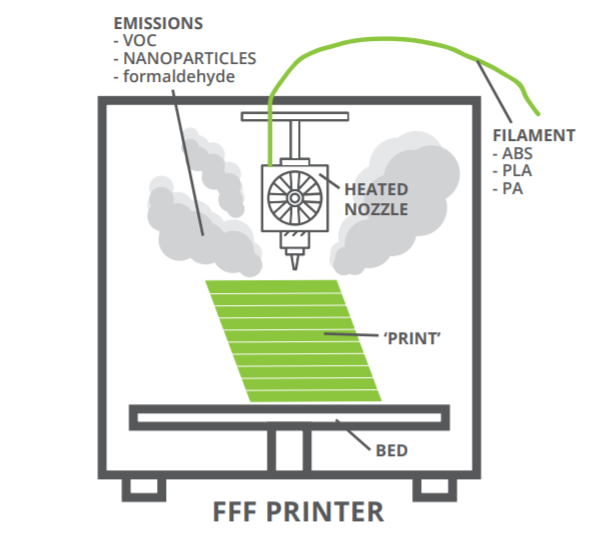

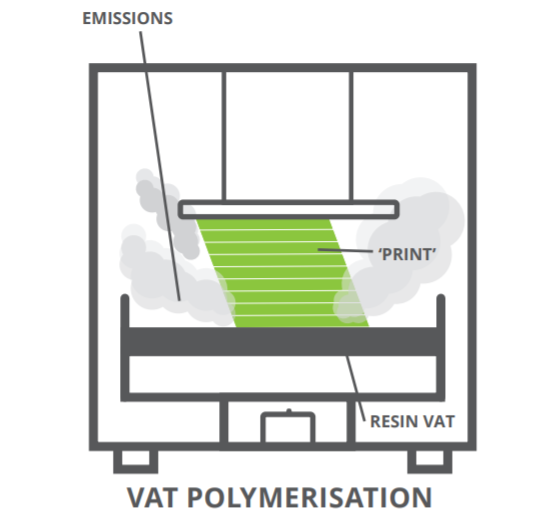

The study looks at the presence of harmful airborne contaminants produced by 3D printing processes like fused filament fabrication (FFF) and vat polymerization, and how printer manufacturers can protect the health of employees and product quality through integrating effective filtration systems.

“The report highlights the importance of installing effective filtration solutions that can help capture and remove any potentially harmful emissions,” said Ross Stoneham, Product Manager – 3DP & Growth Markets at BOFA. “This will not only help protect operatives from potentially harmful airborne contaminants, but will also ensure that resulting product and the machines remain free from contamination.”

Addressing the hidden dangers of AM

Since 3D printing often involves melting and sintering, one particular health and safety concern is the emission of airborne contaminants, which can come in all shapes, sizes, and smells.

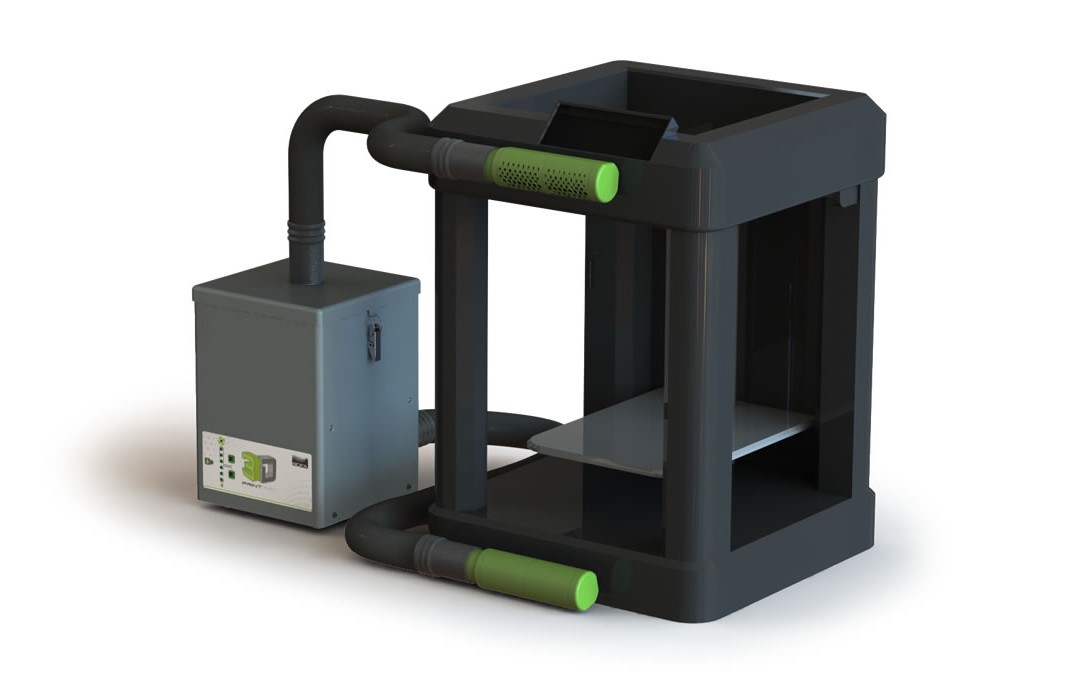

A leader in portable fume extraction technology, BOFA has been developing a portfolio of products specifically for the additive manufacturing industry that can help reduce the risks associated with airborne emissions produced by 3D printers.

In July, BOFA signed a distribution partnership with France-based 3D printer supplier Atome3D to offer its 3D PrintPRO air filtration products. The devices can be integrated into third-party 3D printers in order to capture any harmful fumes and particles emitted during the printing process.

Such airborne contaminants include ultra-fine particles (UFPs) which are often in the nanoparticle size range, while volatile organic compounds (VOCs) have distinctly unpleasant odours.

The detrimental effects of both types of emissions have been well-documented before, with organizations such as the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) publishing health and safety posters specifically targeted at 3D printing.

Elsewhere, researchers from Seoul National University have previously investigated the effect of nozzle temperature on the emission rates of hazardous particles during FFF 3D printing, and scientists from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have also studied VOC emissions during FFF 3D printing, this time looking at composites such as carbon fiber-reinforced ABS.

BOFA’s 3D printing emissions report

BOFA’s research paper focuses on two 3D printing processes in particular: FFF and vat polymerization techniques such as stereolithography digital light processing (DLP). The study aims to better educate the 3D printing market on the impact of 3D printer emissions for them to be used in a more informed and safe way.

Both FFF and vat polymerization processes are popular with entry-level users, however their design often requires frequent manual loading, handling and process optimization which all occur in close proximity to the printing chamber. This means there is a greater potential for exposure to airborne emissions to the operator.

Among other findings, the report outlines how the temperature of 3D printer nozzles dramatically influences the volume of particles generated by FFF processes. An increase in nozzle temperature decreases the average particle size generated during printing, which means they are able to more easily penetrate the human body and subsequently impact negatively on an individual’s health.

The research paper also found that gases emitted by FFF printers also include VOCs, which can potentially cause users to experience headaches, eye irritation, skin irritation, and even occupational asthma.

Various filaments were also identified as giving off different levels of emissions. For instance, ABS filaments gave off styrene, acrylonitrile and butadiene, while PLA filaments released lactide and organic acids. However, as the odor generated by printing with PLA is much lower than with ABS, many believe the risk to be much lower or even non-existent, but the data shows there are VOCs being generated for both materials, regardless of whether a person is able to detect with their senses or not. This is why ventilating a room by opening a window is standard practice for most users.

Moving on to vat polymerization, and the photoreaction caused by heating the liquid material in its natural state has also been proven to emit airborne matter. As the printing process converts the resin into solid material, not all of it ends up in the finished part and subsequently nanoparticles are generated. BOFA’s report also focuses on the emission generated during post-processing through acts like sanding, gluing, and solvent-based finishing.

How harmful are 3D printing emissions?

Understanding the health hazards associated with the air you are breathing while operating your 3D printer is important. However, while it is useful to divide these 3D printing emissions into VOCs and particles, the compounding effect of both particles and gases should also be taken into account.

According to BOFA, users have the right to understand the emissions from their 3D printers, and at the same time, employers should be helped in complying with their legislative responsibility to protect their employees.

The report states that particle size is particularly important to this understanding, as the size of the particles emitted during printing affect where in a person’s respiratory system they are deposited. The smaller a particle is, the further into the respiratory system it is able to penetrate and the more harm it can do. BOFA states the interaction of gases with the respiratory system must also be considered, as chemicals are able to be absorbed through both a user’s lungs and skin.

Mitigating the impact of emissions

In addition to educating readers on the hazards of 3D printing emissions, BOFA’s report also sets out a number of mitigation strategies to protect users.

One of the most effective protection strategies is the use of engineering controls such as fixed ventilation systems and direct extraction technologies. However, while both techniques are reasonably effective in separator the user from the hazard, they aren’t always able to completely contain the emissions produced during the process, and these can be released at the end of a build when the operator retrieves the printed part.

Administrative controls and personal protective equipment (PPE) are also ways of protecting against emissions hazards, however these simply limit an individual’s exposure rather than controlling the hazard itself. In the report, BOFA believes the greatest level of protection offered against the risk of 3D printing emissions is a specialist direct extraction (LEV) system.

Looking to the future, BOFA foresees a direct correlation between the increasing productivity of 3D printers to the amount of material printed, and in turn the amount of emissions being produced. The research paper suggests that greater adoption and maturation of additive manufacturing in the future is likely to bring greater focus on making sure the technology is safe. With this, machine and material manufacturers have a responsibility to ensure they carry out adequate testing to ensure their products are safe.

BOFA will be presenting the full findings of the research paper at its stand at Formnext next week, and those wishing to find out more can download the paper here.

Subscribe to the 3D Printing Industry newsletter for the latest news in additive manufacturing. You can also stay connected by following us on Twitter and liking us on Facebook.

Looking for a career in additive manufacturing? Visit 3D Printing Jobs for a selection of roles in the industry.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel for the latest 3D printing video shorts, reviews and webinar replays.

Featured image shows how the 3D PrintPRO 3 integrates with 3D printers. Image via BOFA International.