Adrian Sugar and his team at the maxillofacial unit at Morriston Hospital in Wales have long known that 3D printing would change the field of plastic surgery forever. For the past ten years, they’ve been watching the technology mature so that it might be incorporated into his practice, performing reconstructive head and neck surgery. In aiding Stephen Power, the victim of a traumatic motorcycle crash, with a recent facial reconstructive surgery, Morriston Hospital Center for Applied Reconstructive Technologies in Surgery (CARTIS) was able to demonstrate the extent that 3D printing can be used in such procedures, using the technology to rebuild his face at every stage of the process.

Sugar explains the maxillofacial unit’s initial interest in 3D design in the mid 90s, “We started out with this interest in 3D software to see what we could do with greater precision – partly in making implants to put in patients that were custom-made, partly to do trial surgery on physical models.” Up until the software was capable for their work, Sugar and his team would send CT scans of patients to the National Centre for Product Design + Development Research at Cardiff Metropolitan University, the other half of the CARTIS team. Product Design + Development would then make a physical model that would allow the nine CARTIS surgeons to rehearse surgeries for cleft palates, deformities, and head and neck cancers.

Since then, they’ve been moving away from physical models, in favour of the virtual, thanks to improvements in 3D software, with Sugar saying, “We’ve now spent the last eight or nine years trying to get rid of the models and to focus on virtual models and virtual planning. The only time we get into the physical side of things ideally is when we have something that we either put in the patient on a permanent basis or we use as a guide to the surgery during the operations. It’s completely changed the focus of what we do.”

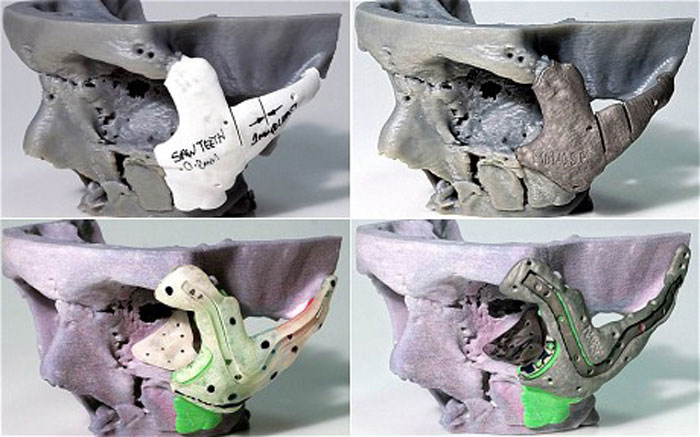

Such surgeries include that of their recent patient, Stephen Power. Power, 29, received multiple trauma injuries in his 2012 accident, breaking his top jaw, nose and cheekbones and fracturing his skull. Improvements in 3D printing have made it possible for Sugar to have custom prints made from Power’s CT scan, both for implant and to create surgical guides. By scanning their patient’s skull, they were able to reestablish the symmetry Power lost after the accident, printing a symmetrical 3D model of his skull.

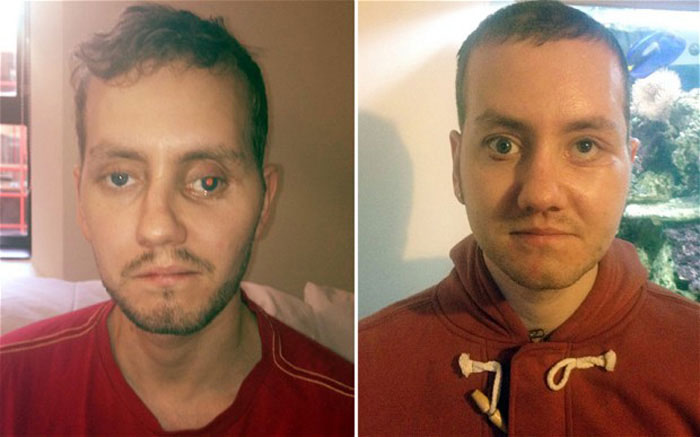

With a set of cutting guides and printed plates matching Power’s CT scan, The CARTIS team performed their surgery, first re-fracturing his cheekbones along the guides and, then, implanting a 3D-printed titanium piece to hold his bones in place. Previously, in order to hide his injuries, Power wore a hat and glasses, concealing his face in public. After the surgery was complete, Power felt as though it was “totally life changing”, adding, “I could see the difference straight away the day I woke up. I’m hoping I won’t have to disguise myself — I won’t have to hide away. I’ll be able to do day-to-day things, go and see people, walk in the street, even go to any public areas.”

Sugar says that the new technology has changed the way he creates custom implants, calling Power’s surgery “incomparable” to anything his team had performed in the past. “Without this advanced technology, it’s freehand. You have to guess where everything goes. The technology allows us to be far more precise and get a better result for the patient.” It’s hoped that Power’s surgery will encourage the use of 3D printing in the medical field more quickly and, in order to further educate the community on the technology’s benefits, Power’s operation will be part of the Science Museum in London’s “3D Printing: The Future” exhibit, previously covered on 3DPI.

Source: Yahoo!, British Council