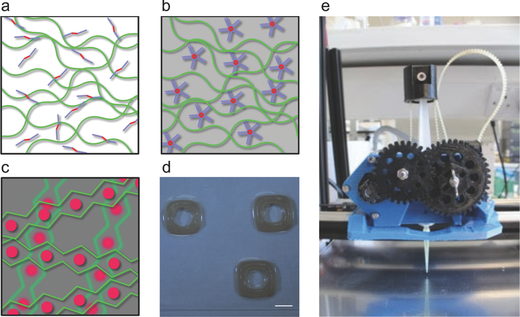

One challenge facing the wider use of 3D bioprinting, is the range of inks available for 3D printing structures. Alginates, extracted from types of brown seaweed or algae, make up a sizebale base of materials used in the development of bioinks. When combined with other materials, alginate properties can be improved for example, to become more sturdy or more attractive to cells. Recent research from the University of Bristol combines alginate with the synthetic polymer Pluronic to make a new bioink that ‘offers a multitude of advantages for bioprinting, compared to single-component gel systems’. Namely the high-resolution of the print and its resulting ability to produce a naturally faithful cell structure.

A closer look at the materials

Pluronic is a BASF brand name for a type of block copolymers, based on a combination of ethylene oxide gas, and propylene oxide liquid. There are many different types of Pluronic and these materials are commonly used as agents within other products to thicken, and disperse molecules, amongst other things. In this research, Pluronic was used due to its ability to form a gel when heated for extrusion. BASF are also developing materials for HP’s Multi Jet Fusion 3D printer.

The researchers were able to 3D print a sacrificial structure in the Pluronic/alginate hybrid polymer that saw the Pluronic dissolve from the structure, as Adam W. Perriman, the corresponding author of the paper says:

What was really astonishing for us was when the cell nutrients were introduced, the synthetic polymer was completely expelled from the 3D structure, leaving only the stem cells and the natural seaweed polymer. This, in turn, created microscopic pores in the structure, which provided more effective nutrient access for the stem cells.

Alginate is used frequently in bioengineering for ‘several essential properties’ as outlined by Albert Ryszard Liberski, in a review of alginate for QScienceConnect. These properties include ‘its ability, when dissolved, to increase the viscosity of aqueous solutions’ which is especially important for 3D printing extrusion, and that an alginate requires no heat to form a gel.

Other 3D bioprinting applications

Previously, we have seen the University of Florida combine alginates with silk proteins to 3D print veins. Other inks created at Harvard University add plastics and glucose into the bioink mix. Ultimately, the goal of these mixtures is to create structures suitable for replacing living tissue and organs for both testing and transplant purposes.

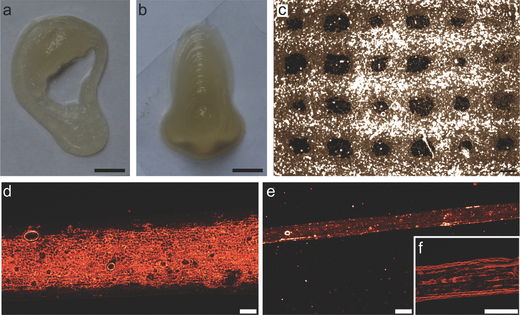

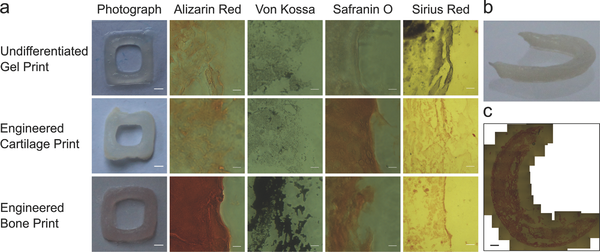

The team used a MendelMax 2.0 RepRap 3D printer to make the structures by modifying the print head, and successfully produced a full sized ear, nose and hollow squares representing cartilage and bone. After a period of 5 weeks, all the structures were able to retain their shape, suggesting that they would be suitable for further research.

Featured image shows brown seaweed under the sea. Photo via: vsprotista on weebly