Scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the Indian Institute of Technology Madras have developed a novel 3D printed microfluidic bioreactor that’s capable of growing self-organizing human brain tissue.

Using SLA 3D printing and an everyday dental resin, the researchers were able to create live neural cell-culturing organ-on-a-chip devices, and a bioreactor for growing them within in-vitro conditions. At a cost of just $5, the team’s setup could serve as a less expensive alternative to commercial culture dishes, when it comes to drug testing and developing treatments for illnesses like dementia or autism.

“Our design costs are significantly lower than traditional petri dish or spin-bioreactor-based organoid culture products,” explained study author Ikram Khan. “In addition, the chip can be washed with distilled water, dried, and autoclaved and is, therefore, reusable.”

Optimizing brain cell monitoring

By culturing pluripotent stem cells within an in-vitro environment, it’s possible to grow them into miniaturized organs, or ‘organoids,’ such as kidneys, hearts or indeed brains. Such organoids can be useful drug screening tools for clinicians, but they need to be grown within incubated conditions, and monitoring them closely can disrupt their development.

Organoids also require a steady stream of nutrition to survive, but as they get bigger over time their cores tend to become cut-off and malnourished, damaging their cell viability. By contrast, lab-on-a-chip devices are increasingly enabling scientists to culture smaller cellular volumes, with a higher degree of freedom and at a more accessible price point.

While these microfluidic systems have traditionally been created via soft lithography, the multi-step technique remains limited when it comes to design flexibility. To combat this, the U.S-Indian researchers have therefore adopted 3D printing to produce a bioreactor that not only streamlines production, but enables close, non-invasive cellular control.

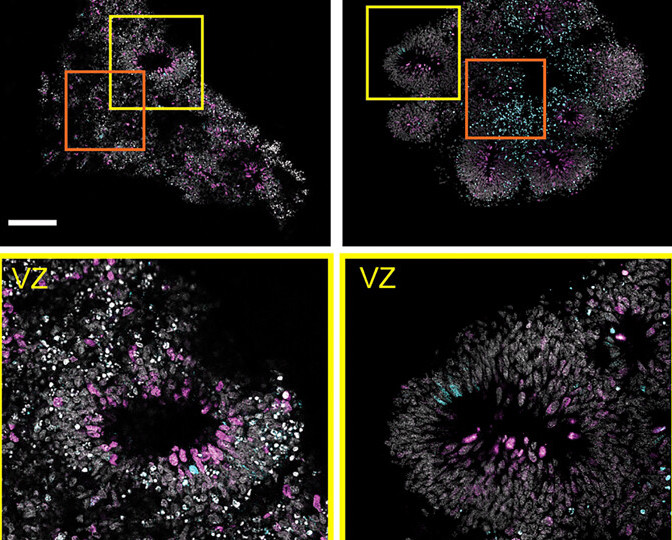

Growing a human neocortex

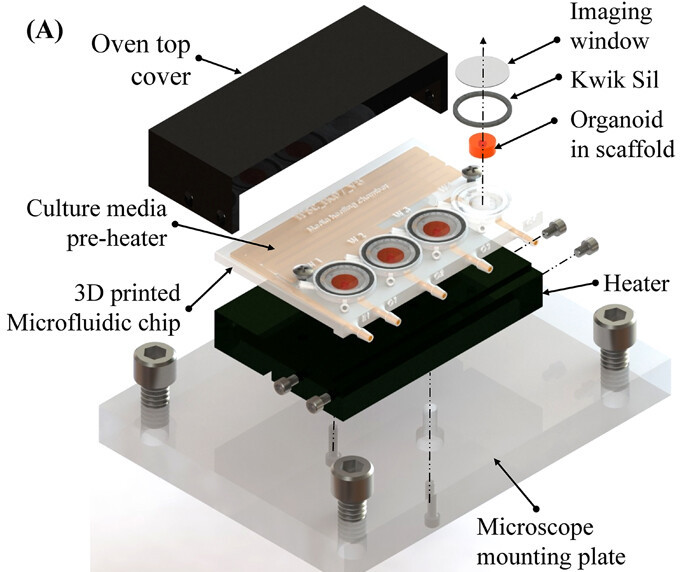

Within their experimental setup, the scientists used a Form 2 3D printer and biocompatible resin to produce microfluidic chips with built-in ‘imaging wells,’ that enabled them to culture organoids long-term. Once seeded with matrigel-embedded neural cells, the devices were covered with a transparent glass disk and heated in a custom-built bioreactor, which allowed the team to closely monitor their organoids’ progress.

Each well featured a thermistor port, meaning that drugs could be delivered in-vitro via cannula in a hermetically-sealed process. According to Khan, the team’s novel setup allowed “constant perfusion of the culture chamber which more closely mimics a physiological tissue,” keeping the organoid’s core nourished and ultimately reducing cell death.

During testing, the scientists were even able to culture their stem cells into a ventricle that resembled a neocortex, the cerebral tissue responsible for higher brain functions. Although the team only monitored their organoid’s progress for 7 days, they witnessed no dip in cell viability, and believe that they could be grown for extended periods in future.

For now, the researchers are working to make their chips more efficient via the addition of valves and pumps, but in the longer term they see their devices being applied within industrial drug testing settings, providing users with a cost-effective means of modelling the interaction between pathogens and the human brain.

‘Organ-on-a-chip’ microfluidics

Often referred to as ‘organ-on-a-chip’ devices, cell-laden microfluidic systems hold significant potential when it comes to tackling deadly diseases and testing drug efficacy. Researchers at the University of Stuttgart and Robert Bosch Hospital, for instance, are currently working on a 3D printed tissue platform that could be used to model the progression of cancerous tumors.

In a similar vein, Harvard University scientists have developed a functional 3D printed heart-on-a-chip device, with the ability to self-contract and mimic the electrophysiology of the real organ. Using a system of sensors, the team were able to closely monitor the organoid’s reaction to toxic substances, lending it potential drug testing capabilities.

A team based at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, meanwhile, have deployed ceramic 3D printing to produce a blood vessel replication device. The scientists’ eight-sided chip could enable the in-vitro development of multiple different tissue types via a single and versatile multi-channel microfluidic platform.

The researchers’ findings are detailed in their paper titled “A low-cost 3D printed microfluidic bioreactor and imaging chamber for live-organoid imaging.” The research was co-authored by Ikram Khan, Anil Prabhakar, Chloe Delepine, Hayley Tsang, Vincent Pham and Mriganka Sur.

To stay up to date with the latest 3D printing news, don’t forget to subscribe to the 3D Printing Industry newsletter or follow us on Twitter or liking our page on Facebook.

Are you looking for a job in the additive manufacturing industry? Visit 3D Printing Jobs for a selection of roles in the industry.

Featured image shows a schematic of the scientists’ 3D printed bioreactor. Image via the Biomicrofluidics journal.