After first looking at the America Makes institute back when it was called the National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute, I began wondering what the Department of Defense (DoD) and the defense industry want with 3D printing. If the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) represents at all what the DoD’s interests in the technology are, then 3D printing for the defense industry means keeping ahead of global competitors, bringing war fighting technology to the battlefield much more quickly, and making faster innovations and improvements to technology when it’s already in use. In Aaron Martin and Ben FitzGerald’s report for CNAS, titled “Process Over Platforms: A Paradigm Shift in Acquisition Through Advanced Manufacturing”, the authors argue that, to achieve these ends, the Department of Defense should pursue research in Additive Manufacturing, robotics and unmanned aircraft systems (UAS).

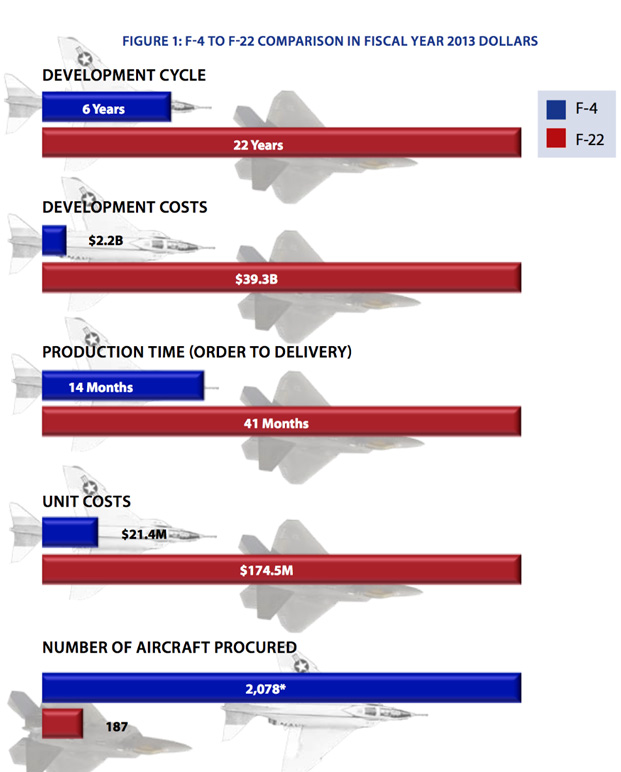

Because of the significant investment needed to field modern military aircraft, the DOD often plans to continue operating them for 20 to 50 years after they reach IOC. Current plans call for F-22 retirement as late as 2049, nearly 45 years after reaching IOC and 66 years after the initial request for proposals. If such plans had been in place at

the end of World War II, the United States would have retired the F-86 Sabre around 2011. System capability cannot remain static for such a long period, so the DOD continues to invest in research and development and modifications for aircraft programs to improve postproduction capability.

This, as you might guess, prevents the DoD and defense manufacturers from innovating quickly.

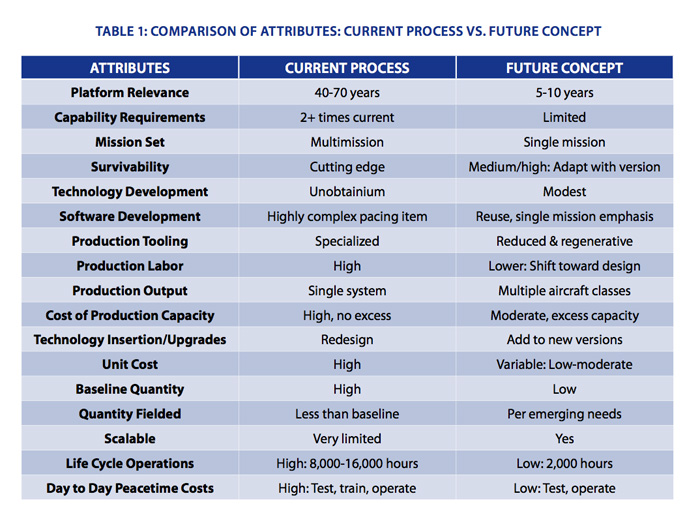

What the authors suggest is that the DoD instead focuses on new, efficient and automated manufacturing techniques. Additive manufacturing, as the report points out, allows for the production of complex parts, while reducing material costs and the total number of components in a given system. Combined with advanced robotics, it may be possible to create a manufacturing system that both prints and assembles parts without the need for much human intervention. Traditional manufacturing methods would still be needed to install and produce some components, “such as engines and sensors, for which AM processes are either less efficient or incapable of production”, but the authors argue that such a system would be able to reduce the time and cost of manufacturing new aircraft by a great deal. Instead of focusing a huge amount of time on producing new planes, an automated process would allow for quicker cycles of development:

The new paradigm would be characterized by shorter, more frequent acquisition cycles based on an iterative development process that could quickly develop many different aircraft systems, thus allowing planners to focus on nearer-term, and therefore better understood, threats.

Each development cycle would conclude in a few years, and the product of each cycle would be a different type of aircraft to be built from a common assembly line that integrates AM with robotic assembly. Planned quantities of any one aircraft type would likely be low, but the common assembly line would be designed to increase production of any developed aircraft rapidly, as needed. The unmanned systems could be flown by “digital pilots” guided by human battle managers. Since the operational value of the system would be short, requirements could be more modest and oriented toward the short term. The short operational life span – and reduced training hours required by unmanned systems – would also cut aircraft fatigue life requirements to lower unit cost.

Such a manufacturing process is already being pursued by iRobot, makers of several other DoD vehicles, who filed for a patent on an all-in-one 3D printing and assembly station.

The authors then go on to argue that the DoD should focus on manufacturing UASs to further increase the efficiency of our military. Pilots of unmanned aircraft require fewer hours of training than manned aircraft, as pilots can be trained with simulators alone. On top of that, in the near future, it may be possible that UAS pilots could manage entire fleets of drones. Altogether, the lifecycle cost of an UAS is about half that of manned aircraft:

According to a 2011 analysis by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, “the total lifecycle cost of the unmanned system is less than half the cost of the manned system.” These savings accrue from the reduced training flying hours, smaller procurement requirements and fewer personnel needed to sustain the aircraft throughout its lifetime. The greater use of autonomy in UAS offers the opportunity to scale up the number of aircraft and gain significant personnel efficiencies.

Of course, the report focuses on aircraft production. When it comes to other technologies, the integration of 3D printing and robotics into manufacturing may be somewhat different, the authors point out.

Because this report is written by Dr. Aaron Martin, Director of Strategic Planning at Northrop Grumman, and Ben FitzGerald, Senior Fellow and Director of the Technology and National Security Program at the Center for a New American Security, it will necessarily be biased in favour of defense manufacturing. The blasé attitude with which it is written is terrifying in comparison to the actual violence seen on the frontlines of war. For instance, the reliance on simulators to train UAS pilots is particularly disturbing:

Since the aircraft would be unmanned, the training fleet could be much smaller because most training could be completed using simulators. Further, instead of acquiring a fleet to meet all potential demands, the DOD could procure a fleet that is large enough to meet operational testing and forward presence requirements.

I hardly need to describe the detachment that might occur with training soldiers purely with simulations of war that may turn human beings into the “potential demands” of a job.

If the Department of Defense were really interested in defending the interests of the American people, it might consider using its significant funds – about $716 billion in US taxpayer dollars in 2013 – to actually address our domestic needs. In December, a long list of non-profit organizations — that did not include the CNAS, coincidentally — wrote a letter to Congress and the White House urging huge cuts to the defense budget in favor of much needed domestic spending. Ralph Nader summarizes the ways that money could be better spent:

The consortium of activists’ are asking Congress to slash the bloated military budget and use the significant savings to enhance critical social programs that actually help people, things like food stamps, Social Security and improved full Medicare-for-all healthcare. They also suggested a massive public works agenda that creates good paying un-exportable jobs in every community around the country — jobs that include clean, renewable energy for the future. And what of America’s crumbling infrastructure? Our clinics, roads, schools, bridges, libraries, public transit, public water and sewage systems and national parks are in dire need of repair and modernization. The savings from defense spending could be used to repair infrastructure — much of which was a product of FDR’s New Deal in the 1930s — and ensure a cleaner, safer, more prosperous America.

Source: CNAS