A Meshbomb is a form of subtle street art, in which an object is “borrowed” from a public location, 3D scanned, replicated, and returned to its original location alongside its new, 3D printed sculptural reinterpretation.

The practice of MeshBombing was conceived by artist Jason Ferguson, who is also a sculpture and design professor at Eastern Michigan University. The purpose – if one requires that artwork has a purpose – of MeshBombing is to create public installations that are discovered by people who use a public space regularly, so that they may notice the MeshBombed objects as new or out of place and, as a result, question their presence.

Examples of Ferguson’s MeshBombs include a series of hot pink copies of a Ganesh statue made progressively smaller. The parade of pink elephants invokes memories of a scene from a Disney movie. With the MeshBomb copy stripped of all of the detail and color found in its master, one’s attention may be drawn to the details in the original that would have previously gone unnoticed. In this way, MeshBombs take existing artwork and subvert it into something else, something playful, harmless, but off kilter and, possibly, perplexing.

To get a better understanding of Ferguson’s methods and motives, I caught up with him via e-mail and the following conversation ensued:

Scott J. Grunewald: Do you have permission to “borrow” the pieces that you replicate? Or to place your prints in businesses? Have you ever been caught installing a piece?

Jason Ferguson: This type of work is strongest when people, including employees, discover them, rather than expect them. I have not been confronted while borrowing or installing a piece so far. I try really hard to be discreet.

SJG: Have you ever gotten feedback from people who have found your art?

JF: There seems to be a nice buzz around the places where I’ve done this. I hear people asking the employees where they come from. The photographer that documents them also fills me in about what people are saying. I have not received direct feedback from people who have found my art because I really don’t take ownership (until now); however, unexpected ‘blind collaborations’ have followed some of my installations. While some works are permanently adhered to surfaces, others are simply set up and left behind. This approach was an invitation to see if people are noticing the works or not. Some sculptures disappeared, either ironically stolen themselves or thrown in the trash, but the best response is when someone reconfigures what I’ve done. This was the case with the Ganesh sculptures; I had installed them in a descending scale arrangement, loosely based on the ‘Pink Elephants on Parade’ scene from Disney’s Dumbo. When I returned to the site a few days later, the statuettes had been separated and they were hidden throughout the café…all were accounted for, they were just moved. So, I gathered them and rearranged them again, this time into a spiral pattern. We ended up having a playful dialogue over the course of a week or two. I don’t know who was on the other end of the conversation, and as far as I know the other person(s) didn’t know who I was either.

SJG: What drew you to street art? Both as someone who is passionate about it and as someone who makes it?

JF: I consider something that I’ve done to be successful if I can manage to get the viewer to think about the work long after having seen it. Street art has the potential to interrupt the norm. I aimed at creating psychologically charged works that would act as a public intervention. I set out to playfully disrupt the day-to-day routine. The MeshBombs I’ve created so far are subtle and very site-specific; they speak directly to what is around them. My hope is that their context raises an uncanny feeling and that the viewer continues to think about them afterwards; maybe even starts to look for them at other sites.

SJG: What do you want your art to say to people? I mean, I understand what it says to me, but what is your intent? Or does it change piece to piece?

JF: With this body of work I am really interested in the uncanny intervention aspect that I mentioned previously. I don’t intend for the works to tell the viewer anything specific, but I set out to create a situation in which the viewer begins to re-experience the mundane.

SJG: Where did you get the idea to start installing 3D printed street art?

JF: I’ve been working with 3D printing for a few years and I was really interested in integrating it into my art practice in a way that conceptually made sense. I didn’t want to force it. Early on I was using 3D printing as part of my idea development workflow. I used it to create scale models and prototype designs to be scaled up for fabrication. It was a way to visualize something in a physical form, prior to jumping into a massive several-hundred-hour project. I think tinkering with 3D scanning techniques was what made me think differently about the implications of a “cloned” object and how an altered replica of something that already existed in a space could be really powerful. A combination of 3D scanning, digital altering, and 3D printing started to make a lot of sense.

SJG: I always expected 3D printing to be used for art, but I expected it to me more popular with pop art. But almost from the start it has been embraced by more traditionally trained, modern artists, many of whom have really pushed the limits of the technology. Why do you think so many modern artists have been drawn to 3D printing as a medium? Why were you?

JF: This is a great observation, but a loaded question! Some of the most intriguing artwork throughout art history is that which confronts the limitations of a new tool head-on and without fear. Experimental processes and the exploitation of limitations carry the art world forward into unexpected territory…this is what artists do! When video cameras became affordable to the mass-public artists immediately bought them and (literally) turned them upside down, slowed the footage, offset the audio, etc. I think that this is the innate nature of the artist; we take things that are accessible to us and we attempt to see them in a new light.

SJG: Do you “reuse” MeshBombs? Or do you tailor them specifically for an individual space? Or can we see zombies crawling out of walls all over the city?

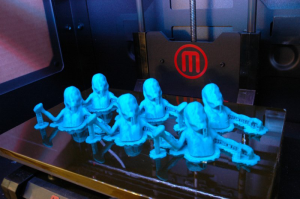

Ferguson creates his MeshBombs with an original MakerBot Dual and then later a Replicaror 2X, however he recently 3D printed and built an open-beam OB1.4 RepRap machine, based on the Prusa Mendel design.

I feel like 3D printing is almost essential to MeshBombing, and not just due to the speed of creating the reproduction. Yes, you could conceivably borrow an object and recreate it by hand, but a 3D printed object looks artificial and it looks like an actual attempt at a replication, not a copy. While that may not be a huge distinction, for me it seems to make the art more interesting.

Of course 3D printing has other uses for a MeshBomber, that aren’t directly related to the works themselves. If you had to install a row of shambling zombie figures in a public place by affixing them to a wall, how quickly could you manage it without being noticed? Ferguson treats his mashbombs the way graffiti artists treat throw-ups – a graffiti bomb with as little detail as possible thrown up on a wall or bus quickly to avoid attention – so speed is quite often a factor. In order to install his zombies Ferguson 3D printed an applicator that allows him to install all of them in one quick motion. That’s quite a functional print.

You can learn more about Jason Ferguson, his MeshBombs at his website where he also has several other examples of his art installations catalogued. And if you decide to create your own MeshBombs, don’t forget to tweet him a picture of your installation @MeshBomb1. And, while you’re at it, tweet it to me, as well @sjgrunewald.