Materials researchers at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, have developed an additive manufacturing-based procedure to make magnesium scaffolds with regular porosity.

While magnesium can be absorbed by the body as a mineral, it is very challenging to be processed by conventional 3D printing techniques due to its highly oxidative nature. Using a 3D printed salt template, ETH Zurich’s method managed to create magnesium structures with ordered pores while retaining their mechanical stability.

Complex controlled shapes can be produced with this method, making the structures ideal as templates for salt leaching. Although this work is only a proof of concept at present, these magnesium scaffolds has the potential for making bioresorbable bone implants.

Biodegradable bone implants

Metal implants are typically used in treatments of complex bone fractures or even missing bone parts. Previously, scientists have 3D printed implants using traditional materials such as bioinert titanium and PEKK. However, these metals often require a second surgery for implant removal.

In contrast, implants made of light metals can biodegrade in the body and be absorbed as a mineral nutrient. Rendering implant removal unnecessary, biodegradable magnesium and its alloys present an attractive alternative as implant material.

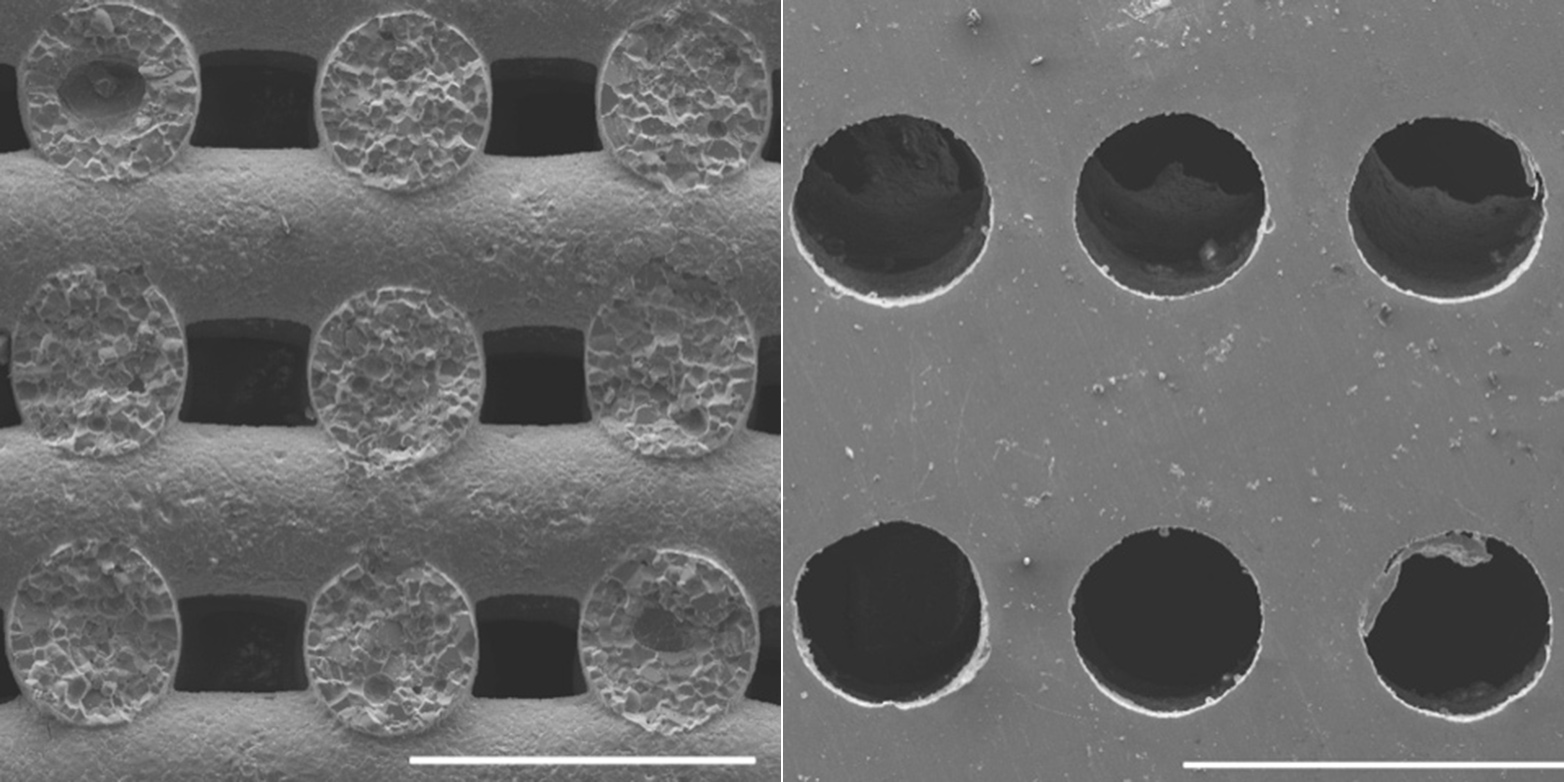

To support bone regeneration, implant design is directed towards the promotion of cellular adhesion and in-growth. Porosity is one of the essential features in encouraging cell growth. Salt leaching is a common technique for preparing porous materials with a vast variety of chemistries. However, its template approach is typically limited to fabricating random porosity and relatively simple macroscopic shapes.

Magnesium scaffolds with custom porosity

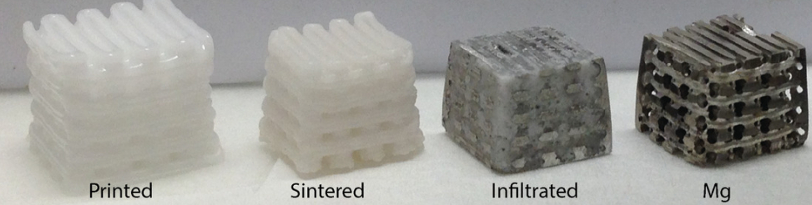

To create a custom porous structure, the ETH researchers 3D printed a salt template. As pure table salt is unsuitable for 3D printing, a salt-based paste was rheologically engineered by tuning the composition of surfactant and solvent. The paste was then 3D printed layer-by-layer via direct ink writing into grid-like structures. Through the printing process, the strut diameters and spacings of the salt template can be tailored, allowing structures to span from the sub-millimeter to the macroscopic scale.

For enhancing the mechanical strength, the salt structure was subsequently sintered. During sintering, the fine-grained materials are heated significantly. To retain the structure of the workpiece, the temperature is specifically chosen below the paste’s melting point.

As a proof of concept, the dried and sintered salt templates were then infiltrated with magnesium melt. Afterwards, the salt templates are removed by leaching with an aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide. This is a typically highly challenging to process by conventional AM techniques due to its highly oxidative nature and high vapor pressure.

The magnesium scaffolds obtained after salt removal have well-controlled, ordered porosity. “The infiltrates obtained in this way are mechanically very stable and can be easily polished, turned and shaped,” says Jörg Löffler, Professor of Metal Physics and Technology.

Application in biomedicine

The tunable mechanical properties and the potential to be predictably bioresorbed by the human body make these magnesium scaffolds attractive for biomedical implants. “The possibility to control the pore size, distribution and orientation in the material is decisive for clinical success, because bone cells like to grow into these pores,” says Löffler. Growth into pores is in turn decisive for the rapid integration of the implant in bone. In addition, he team expects that the process can be extended to tailor pore geometries in polymers, ceramics and other light metals.

3D Printing of Salt as a Template for Magnesium with Structured Porosity is published in Advanced Materials. It is co-authored by Kleger N, Cihova M, Masania K, Studart AR, Löffler JF.

For more of the latest 3D printing research sign up to the 3D Printing Industry newsletter, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.

Create a profile on 3D Printing Jobs now to advertise new academic opportunities.

Featured image shows the template of salt structure (centre) 3D printed by ETH researchers and its magnesium counterpart (right). Photo via ETH Zurich.