Back in January 2017, Prof. Sascha Friesike of the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society (HIIG) gave a keynote speech at the Chaos Communication Congress (33C3) in Hamburg, Germany. In his talk entitled “What we can learn about creativity from 3D printing”, he observed just “how important remixing is for the creative process we see in the 3D printing community.”

Now, taking his research further, Friesike has published a research paper on the subject of “the remix as a form of innovation”, in the Journal of Information Technology together with fellow academics Cristoph M. Flath, Marco Wirth, and Frédéric Thiesse. The paper represents a landmark in the study of the social implications of both additive manufacturing and remix culture itself.

The physical and legal background of remix culture

“Remixing” can generally be defined as the “re-use of knowledge”. This may of course be in the traditional musical sense (sometimes called a “mash-up”), where a published piece is repurposed in whole or in part in order to create something new. Art movements of the 20th century provide many visual examples of the remix: Duchamp repurposed a urinal for his piece “Fountain”, while Warhol used an original publicity photo from the film Niagra to create his iconic “Marilyn Monroe diptych”. Remixing can also take place outside the world of audio-visual media; an often cited contemporary example of a physical (and edible) remix is the ‘‘cronut,’’ a pastry that is a cross-between croissant and a doughnut.

Creativity, rightly or wrongly, has its limits. In the domain of audio and visual media, copyright and intellectual property laws form a minefield that must be appropriately negotiated . Even the slightest perception of insufficiently attributed remixing, repurposing, or sampling can result in a costly lawsuit (even more so if the remix itself becomes commercially successful). While food ingredients are much harder to claim copyright over, even in the culinary world remixing isn’t completely free of controversy. Conversely, in the comparatively recent domain of 3D printing, there is no clear legal consensus. As explained in the Creative Commons blog, a template for an individual 3D design can itself carry licensing information. However, once the file is sent to a printer, this information disappears, and there is currently nothing other than etiquette to guarantee attribution to the original artist.

Remixes – a 3D can of worms

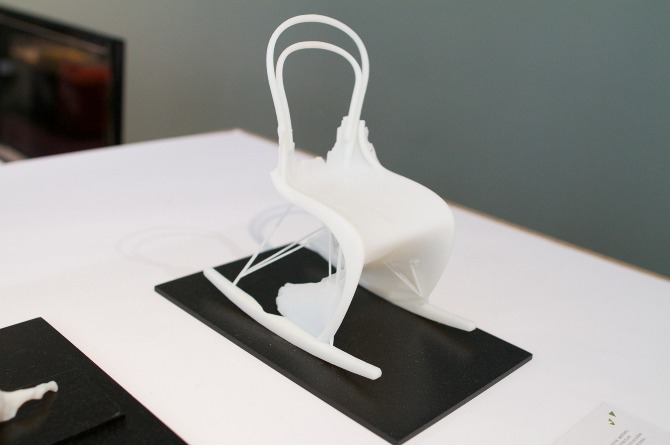

The emergence of remixing in3D printing is arguably natural progress on a journey that has already seen image manipulation and audio-visual mashups fuelled by ever-increasing technological literacy and bandwidth. Add to that the greater availability of 3D printing machines, and you have arrived at your destination: the remixing of everyday objects around us, with the laws of physics the only boundaries.

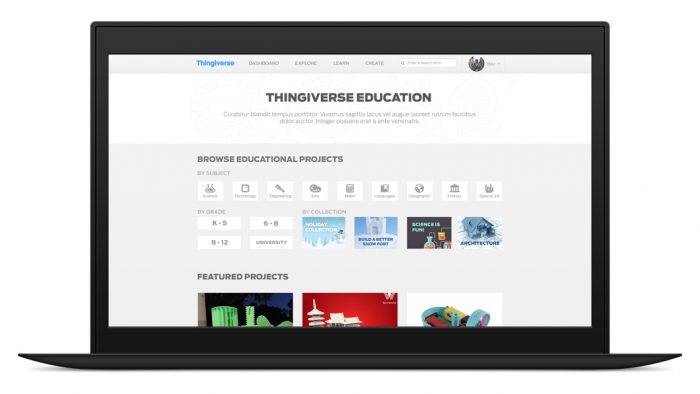

This in turn has enabled online communities to support and circulate templates for 3D printed designs for everything from drones to furniture created from scans of existing found objects (but not weapons or sex toys as they violate the terms of service). That brings us to Thingiverse, the open source platform on which 3D templates can be freely shared (such as these neo-classical sculptures from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York), which is the focus of Friesike et al.’s study.

The study and its conclusions

The study begins by asking: “what are the characteristics and determinants of remix-based innovation in open online communities?” As part of their research, Friesike et al. extracted a dataset of over 100,000 “remixed” designs before organising these schematically into a chain with their “ancestor” and “descendent” designs. Their results identified dramatically different patterns of remixes among users, and showed that the different features of the Thingiverse platform facilitated remixing and reuse activity. The results also demonstrated the diversity of the platform’s community.

The study mainly confirms some self-evident features of Thingiverse, but also presents some unexpected results. First of all it concludes that remixes are as great a source of innovation as isolated original creations. The study also shows that remixes occur along distinguishable patterns, and that remixes not only occur within specific object categories but also in between these set categories. Finally, it concludes that Thingiverse’s user-friendliness is proportional to the innovativeness of its users, owing to their technologically diverse backgrounds. The study thus makes some important recommendations for the management of Thingiverse, with a view to improving innovation amongst its users.

Thingiverse is not alone. In 2016 MyMiniFactory introduced a tool to encourage collaboration. The “coolab” tool can be used to track remixes of a design and is intended to facilitate sharing projects. MyMiniFactory has also recently conducted an academic study looking at how 3D printing can save consumers money.

The implications for creativity

While Creative Commons and the legal sector no doubt play catch-up with the world of remixes in 3D printing, remix culture itself shows no signs of slowing down. What the study by Friesike et al. confirms is that the freedom to create and to express is largely dependent on the freedom to remix, and that remixing should be seen as a form of collaborative innovation, not unwarranted appropriation.

Sign up to out 3D Printing Industry newsletter here to hear more about exciting developments in 3D printing software, and like us on Facebook.