Avi Reichental’s Jewish mother wanted him to be a rabbi. While he didn’t take that particular path, during a long career in tech – prayer has certainly come in handy.

Now the leader of XponentialWorks, a combination of venture fund, advisory firm and product developer, the 3D printing industry veteran has seen it all, from widespread doubt about technology, to frenzied investment, and back to more realistic expectations. But when Reichental started at 3D Systems, the company he led for 12 years, he asked for a benediction.

“I came from Sealed Air, we virtually printed cash,” Reichental, who is affable and chatty throughout our long interview, said. “The same could not be said for 3D Systems at the time. I had to kind of get down on my knees and beg many of our major suppliers to give me time, a new experience for me,” he tells me.

In a move that no doubt would have amused his mother, he also asked for a miracle. 3D Systems needed to raise a capital figure in the double digit millions almost immediately. “It was a fortune at the time, I decided to put half a million dollars of my own into the raise to show not just to my fellow employees, but to show to investors that as the newcomer, the new leader, I’m willing to put skin in the game at that level.”

Today, Reichental is one of the most well-known names in the 3D printing industry and while wary of Monday morning quarterback syndrome he is well placed to provide insight into the opportunities and challenges facing the additive manufacturing sector.

In this candid and in depth interview Reichental discusses the early days of the 3D printing industry, his thoughts about the current market and competitors, how to grow a 3D printing business and where the industry is heading.

The making of an entrepreneur

It was December 1977 when Reichental arrived in the USA from his native Israel, some 26 years before he would take over one of the companies at the cutting edge of 3D printing. “I am a very late-bloomer in understanding that I had a passion and contributions to make to high tech,” he says.

Indeed, the history of the 3D printing industry might have been very different had Reichental’s parents succeeded with their plans for his career.

“My parents sent me to religious high school to what’s called a Yeshiva. They had hope that I would become a rabbi. That lasted for about a year. I didn’t want to go back for a second year”

Unsurprisingly, this rebellious behavior was not rewarded by his parents and rather than be allowed to join his friends at the local high school, he was sent to the Israeli Air Force high school in Haifa. This school in the north of the country served as, “a prep school for aerospace engineering” and prepared Reichental for mandatory military service. Initially serving as a helicopter mechanic, Reichental would later lead a maintenance and overhaul project team responsible for the recently established Sikorsky CH-53 IAF squadrons of the mid-1970s. “That was my exposure to engineering, science, and technology,” and with it came “extensive project and people management”.

Reichental acknowledges that he is a product of his upbringing, “I’m kind of a hybrid between generations that grew up in a post-depression and the post Holocaust environment. My parents came from Eastern Europe, both were Holocaust survivors. I don’t even have pictures of my grandparents, we don’t have anything in our family repository that shows us previous generations.”

He believes that his career was shaped by “the resourcefulness that I think comes from the refugee DNA of my father.” Reichental’s father escaped from Poland to Russia and then to Bashkiria to survive the war, and then back to Poland and took Exodus moving to Israel. “All these stories that I grew up with instilled in me a really strong sense of making it and being an entrepreneur.”

Reichental also credits his respect for science and engineering to the lessons of his father. “He was a career military member and he was a very good craftsman, he taught me from a very young age how to make and fix things.”

This background gave him what he describes as a “hybrid make up”. “I am willing to live with a measure of uncertainty. I’m willing to risk my time and assets to make a difference and make an impact.”

“The older I get, the more it’s reflected in my actions and my investments the products of companies in the [3D printing] ecosystem.”

Moving to New York to marry his first wife, Reichental’s next job was maintenance work of a different kind. “I started in New York City by mopping floors in a nursing home.”

After picking up work as a maintenance shift mechanic, he eventually landed a job at Sealed Air Corporation as a development and project engineer. “Sealed Air wasn’t a killer high tech company, it was the company that invented bubble wrap. These days you would call it an early-stage company. It had about $78 million in revenue and 400 employees, but we had a brilliant CEO.”

Sealed Air CEO Dermot Dunphy, like Reichental, was an immigrant to the United States, Dunphy had grown sales from $5 million to $3 billion. “He had a vision. Dermot said we are going to be a high tech company in a low tech environment and put a lot of emphasis on product development and technology”

Dunphy became Reichental’s mentor and Reichental would spend the next 22 years with the company, moving through the ranks to become one of the top executives at Sealed Air. At least half of those years were spent managing product development and innovation and a series of packaging related patents naming Reichental as the inventor. He remembers his career with Sealed Air fondly, saying with a smile, “For many, many years, I thought this, this is as good as it gets.”

Then during a business trip to London, he received a call from a headhunter asking if he was interested in looking at a California company that did something new. It was called 3D printing.

While 3D printing “wasn’t exactly a household term,” Reichental had a passing familiarity with the technology having used a service bureau to produce prototypes. This recruiter call would push the boundaries of Reichental’s comfort level. After all, he had been safely embedded within a single company now for more than two decades.

Until that point, he says, “My career progression and my evolution as both a person and a leader happened organically and happened within the safety of a company that was doing really well.”

“That was the first time that I had to kind of confront myself and ask myself, am I willing to leave a fairly comfortable cocoon in a company that I invested well over two decades, and go and take on the challenge with a company that has tens of millions of dollars, that was fast running out of cash.” He says that the 3D Systems of that time had, “lots of legacy challenges and issues including the ability to bring products to market the ability to advance materials, a company that was already in the third wave of restructuring.”

Reichental was not overly optimistic about his chances of changing the struggling company’s fortunes. “There was a better than a 50% chance that a year later, I will be out looking for my next gig.” But he also recognized that this was a “unique opportunity to be part of a very different journey”

The recent memory of the 1990s dot com era had also, “left me with skepticism about the potential of high tech.”

Reichental and the 3D Systems years

It is apparent that Reichental’s skepticism was overcome by the 3D Systems founder. “Chuck Hull is an incredible person, he is very creative, innovative and prolific. But in a very gentle way. His presence is felt through his actions, not through his words,” Reichental says.

“When I met him It was after a period in which he was let go by my predecessor. He was brought back into the company to be the interim CEO when I joined after interviewing with him extensively.”

Reichental did not expect to be CEO for 12 years, with a CEO’s “shelf-life” commonly in the three to five-year range. Reichental explains that part of the reason for his lengthy stay at 3D Systems was because Hull also stayed with the company, “We became really, really good partners and good friends and good colleagues. It was a once in a lifetime privilege to work with such a great man.”

It is worth keeping in mind that when Reichental walked in the door, morale at the company was low. “The company was in a state of paralysis and a little bit of shock,” says Reichental. Several years of management by consultants and attempts to right-size the company had left 3D Systems “gutted out” with “a great deal of talent and organizational memory lost. The culture was one of survival, and let’s wait and see,” says Reichental.

“I got there on Sunday night, and on Monday morning, I had an all-hands meeting. And it lasted about 90 minutes. I was very open and told them what I was thinking from the outside looking in, I asked for help, I asked for openness, I asked for the people that had that know-how and the experience to step in to help compress my learning curve, and help me understand the market and the knowledge in the industry.”

3D Systems had significant debt that it needed to repay and was making, “very little recurring revenue.” Financial accounts show $115 million annual revenue for 2002.

“There are a handful of materials in the arsenal of 3D Systems.” Reichental says that most of the materials in those days were legacy DSM materials on the SLA side and Evonik on the SLS side. The company was also in the process of retiring thermal jet and bringing in the InVision at the time. “That was uncharted territory.”

Furthermore, Reichental had inherited a very complex patent litigation between 3D Systems and EOS. “It was very complicated, it was very expensive to litigate, I took it as a challenge to get to know Hans Langer and resolve it as efficiently and as effectively as possible.”

This approach illustrates the value of building relationships with competitors, a pragmatic way to do business. “Hans and I met at Euromold for the first time face to face. Six months or so later, after a series of face to face meetings, we resolved [the case] amicably and we stayed pretty good friends ever since.”

I ask Reichental to summarise his strategy in 2003. His answer is succinct.

“Figure out how to capitalize the company.” he says. And how to do that? “To sell not only machines but also materials, we needed to develop an installed base that will continue to do business with us in the coming years, not just based on a one-off machine sale transaction.”

The route to achieving this would be committing to material development and building up a substantial materials business, with a sustainable revenue stream. A further part of the strategy, Reichental explains, was to, “create a reseller channel which we didn’t have the time to be able to amplify our presence in the marketplace.”

While resellers and channel sales are now a common part of the 3D printing business model, this was less so in 2003. Part of developing this vital network would come in the form of “democratizing the product line, which means, you know, creating better performance solutions for lower price points.”

“When I joined, the large frame SLA systems were north of half a million dollar systems, the SLS systems were in the 400 thousands.” The approach would be to, “make systems that are more capable and less expensive.”

This undertaking would not be accomplished overnight. “It took us until 2006 to stabilise things, by 2007 we had the beginning of scaling and infrastructure.” Things were starting to turn-around for the fortunes of 3D Systems, “and then we had the 2008 recession” says Reichental.

Triggered by the global credit crunch, the recession was a severe blow to enterprises across the world. “The good news is that, unlike many other companies during the recession, we were already in much better shape. We were generating profits, we were generating free cash.”

This meant that by 2009 a strategy of acquiring service bureaus, including Quickparts, was put into practice. “We had a good run on this strategy through 2013,” says Reichental.

It is this strategy of acquisitions that Reichental is frequently associated with. In consumer products and desktop engineering products 3D Systems would acquire “ongoing startup businesses that are kind of modest in size,” he says, adding that sometimes the rationale for the purchase would be to acquire a piece of technology “that we deem to be mission-critical to building that business.”

Another category of acquisition was building up the on-demand parts manufacturing business, “The cherry on the top was the acquisition of Quickparts itself and the online virtual manufacturing platform.”

Healthcare was a third area for development. 3D printing, he realized, could merge with this field, providing innovative solutions and untapped growth. Surgical guides, implants, software and services for both simulation and guidance were all areas where additive and related technology could be deployed.

3D Systems acquisitions included Medicare Modeling and Simbionix and a few others including parts of Layerwise in Belgium. Eventually, they were consolidated into what Avi believes is “one of the most successful businesses within 3D systems”, the healthcare division.

A move into desktop 3D printing, and the beginning of the hype

3D Systems had long focused on the industrial 3D printing market, but upon introduction to the RepRap project, Reichental says he was ecstatic about the opportunity.

That introduction came after seeing Bits and Bytes at a trade show in Anaheim,“I was blown away,” he says. “To me it was a paradigm shift in comprehension that something is going to happen to FDM as we know it and that there is a vibrant community out there in in in the maker community that’s driving it.”

“I was blown away”

Bits and Bytes was acquired in 2010 and was Reichental’s first introduction to the burgeoning maker movement. “I said to myself, ‘Wow, this kind of technology which you know, obviously came from Bath University, from Adrian’s [Bowyers] RepRap project, ‘wow this could change everything.’ It was a good enough tool to sit on engineer’s desktops and provide the simplest of functionality for everyday design iterations or gauges and jigs and fixtures.”

Around this time 3D printing began to enter mainstream consciousness, and many people thought anything was possible. “Or as others tend to call it, the hype period,” says Reichental.

“It was really surprising, and not that obvious. For many of us that were in the middle of it, we were probably the slowest to understand what was happening around us, because we’d been doing it for so long at that point in time.” He continues, “The idea that one day 3D printing would become a household term, it was just incomprehensible to us.”

This realization began to dawn after a 2014 cover feature by The Economist on the third industrial revolution. “I was checking into a hotel and gave my business card. The receptionist said to me, oh, you’re one of those guys in 3D printing, I just read the article.” A week later at Charlotte Airports car rental desk Reichental was met with the response “Oh! 3D Systems, you guys are one of the players in the space.”

“I said to my colleagues, “Something magical is happening. The world is beginning to understand what we do. There was a general awareness.”

After the Bits from Bytes acquisition, 3D Systems set out for CES. MakerBot and Bre Pettis had already been attending the Las Vegas show for several years and 3D Systems could only get a “tiny space”. “We realised that something is happening. Certainly attributed to either the maker movement or education.”

At that point, “The idea that a 3D printer could be in every home became an objective and a target that in those years of 2012, 2013, 2014 seemed within reach,” he says.

The 3D printing industry took some unexpected turns during this period, including the appointment of Will.I.am as Chief Innovation Officer at 3D Systems. “I realized the way a consumer audience will respond or react will depend upon tastemakers or influencers, the decision-making process is very different [than professional users],” he explains.

“Will.I.am, in particular, had consulted for Intel and worked closely with Apple. He was in the process of developing quite a few connected lifestyle products and had a lot of knowledge and understanding of the world of 3D printing.”

Will.I.am would, “influence the design of the final generation of the Cube” and championed the Eco cycle, which was a 3D printer co-developed with Coca Cola to recycle PET bottles into filament.

“It’s easy to be a Monday morning quarterback about such decisions, and often they look like a cheap move to leverage a celebrity and attract headlines. Will.I.am is not that kind of guy, he was already the co-founder of Beats by Dr Dre”. Apple bought that business for $3 billion in 2014. “The guy’s impressive! If I had I to make the same decision today in the consumer field I would not hesitate to reach out to him again.”

Change was coming now, and fast.

“Then we hit the period of desktop democratization,” says Reichental. “The rise of Makerbot and the entry of much cheaper alternatives from Taiwan and China. And of course, our own attempt to create a family of entry-level desktop printers, because we realized that if we don’t cover that base well companies will eventually begin to swim up because they will become the entry-level.”

He cites Formlabs as one company that has done extremely well in this area.

There was substantial optimism and early success in the emerging desktop FDM/FFF market, within the space of a few years it “generated revenues of $35 million per annum, more or less from zero.”

There was also a race for user-friendliness, “the early Cube series and MakerBots required a lot of tinkering. There were all kinds of user friction issues that screamed user unfriendliness.” Furthermore, “there was a great deal of need for content.” Many users were inexperienced with design software and there was a need “For content that “people could actually use and modify and customize. And so we all tried to simplify the way that CAD could be generated. Everybody tried to do that. I think the best efforts came from Autodesk.”

“We all tried to figure out how to digitize and reverse engineer and of course, we’ve introduced a few good and affordable scanning devices to allow the non-engineering user to basically take pictures, if you will, in 3D to be able to digitize and replicate. We launched sites like Cubify, and tried to create the whole experience and narrative about the 3D printed lifestyle, whether in fashion or in art.”

The plan was to create a “sticky and recurring behavior around the promise of 3D printing for education, for hobbyists for home use.” This would see the company venture, “even into food printing,” and opening a culinary kitchen in Los Angeles.

On a panel in 2011 Reichental made his predictions. “The vision in those days was that the consumer side of 3D printing is going to the mainstream, that printers will increasingly become more and more affordable and will reach price points of below $200. Which actually happened.”

“We wanted to see 3D printers fully integrated into STEM and STEAM and not only in high schools and middle schools but also in elementary schools.” He continues, “We expected printers would be part of robotics teams around the world and also in libraries around the world.”

While much of this has taken place, with varying levels of adoption the 3D printer that sits in the living room of every home in America has yet to materialize. Asked if he thinks that day will still come, Reichental smiles and punts the question.

“The danger of making predictions into the future, which I never hesitate to do, even though every now and then I’m wrong, the danger is the timing.”

The voice of experience: How to thrive in the 3D printing industry

Reichental observes that the 3D printing industry has changed significantly since his early involvement, “It’s a tale of almost two cities,” he says, referring to the state of the industry now versus when he first began. “On the one hand, you have the incumbents, that have serious revenue in the six, seven and eight hundred million range.” At the other end of the spectrum are, “younger competitors” with a different approach, who ”are not trying to attack the entire portfolio, but are segmenting and leading.”

“So you have companies like Carbon that segment and lead in high-performance manufacturing solutions. You have companies like Desktop Metal that are coming and segmenting and leading in what I would call casting alternatives. You have companies like Formlabs that are segmenting and leading in the core of the global rapid prototyping.”

Reichental notes that the three companies mentioned above (Desktop Metal, Formlabs, and Carbon) have a combined venture capital valuation above that of several publicly held companies that are generating much higher revenue. These public companies are “unable to respond and react in an agile way,” but one advantage for companies like Stratasys and 3D Systems is channel access, “which means that they, at least to a large extent, still have some measure of control over the reseller channel.”

Channel dynamics are changing with consolidation taking place and with that, “you have reverse leverage vis a vis the OEM”. Joining the legacy players and start-ups are another kind of competitor, companies like HP, “a very experienced and deep-pocketed player.” To thrive in the current competitive landscape he says, “Channel access, education access, and brand recognition are the three most important assets that companies have.”

How do companies succeed in this brave new 3D printing world? Reichental has plenty of advice.

“If I was sitting on the board [I would] find the best ways to leverage the access that you have to the markets both directly and with partners.” Furthermore, he suggests trying, “to divest yourself of all activities that create friction and minimize your agility, and focus in the areas that could give you the highest growth invest in those. Some of the other activities become a little bit lighter and more agile because your future success will not depend on today’s consolidated revenue, it will depend on your revenue generation abilities in the future. And those may come from different sources.”

He notes that “Today, capable startups can have unlimited access to capital,” pointing to Carbon and Desktop Metal as examples. “So the rules of the game have changed, the playground has changed. Behaviour has changed.”

“That would be my advice without wanting to be a Monday morning quarterback.” He acknowledges how challenging it is to lead large enterprises, “I don’t want to come off as arrogant or as a pretentious wise old man.”

“A different lense is required,” he says, “In many cases, the incumbents are actually trapped because they have a great deal invested in legacy technologies. And it’s very, very difficult to throw away a few decades of investments in a certain technology or in certain software architecture and disruptive innovation.”

Learning from mistakes

With any career spanning decades, inevitably there are decisions that you regret when you look in the rearview mirror. I ask Reichental about some of the choices he considers a mistake, and what others can learn from these. “There are a lot of classic challenges in the life of an early-stage company that are kind of cookie-cutter,” he says.

“The first challenge is how do you know that you actually have a product?” Determining whether a revenue-generating idea is not a “one-off or a fluke” requires a great deal of “disciplined process” he says. This is vital to prove that a product, or service, exists and that it is possible to get repeat customers or end-users. Creating the right feature set, value proposition and pricing are also important areas to tackle before an approach – an area that Avi believes is more difficult.

Scaling is where both younger and larger companies, “tend to fail” Reichental says, and he admits that he is not immune – over three and a half decades the 3D printing mogul has “seen and personally failed in all of these aspects”.

However, the “cardinal sin” is when companies “end up spending over 90% of our executive management time making sure that we nailed the technology, the product, the manufacturing the operational side of it, but we don’t spend nearly enough time nailing the business model”.

This includes spending time on the go-to-market strategy, and “how to carve out capabilities and niches” where the company can differentiate itself and “punch above the noise”.

This is particularly applicable to the present additive manufacturing landscape where Reichental believes the influx of enterprises is not matched by an increase in innovation. “Many [enterprises] are kind of mimicking each others’ business models,” he says, “Its me too, a little faster, me too a little cheaper and me too better materials.” He says that few companies have succeeded in creating a differentiated value proposition and carved out a “distinct message and voice”. For companies who avoid this cardinal sin, “It’s a homerun, probably the most significant accomplishment for a company and above and beyond tech.” On the flip side, those who fail will most likely “squander all the efforts that are invested in products”.

The world of 3D printing unicorns and funding ventures

With experience in setting up acquisitions through 3D Systems and now arranging deals via XponentialWorks, Reichental is well placed to provide insights into the financing system in the market. He says that while there is an abundance of capital for companies with the right portfolio, the criteria for investment varies depending upon the type of company. “3D Systems, Stratasys or any publicly-traded company has access to capital markets at any point in time, it’s always better to do it at a time when the company is performing well as the company becomes less diluted.” He adds, “They have to be careful to do it in seasons when it is advantageous.”

On the other hand, “Carbon is a unicorn that gets measured on a different metric. It’s not about earnings per share, it’s about growth, market share, and total addressable market. They are governed by a different metric, it’s called unicorn velocity.”

“You have a combination of Silicon Valley investors, VC, and strategic investors that in every season are willing to put in hundreds of millions of dollars and take the valuation of the company higher. It’s a different set of circumstances. The company will eventually IPO with a future revenue generation horizon that will allow the company to grow into that valuation.”

Carbon is now valued at $2.4 billion, which is a revenue multiplier valuation of between nine and twelve times. Reichental observes, “The question is at what point in time [does Carbon] have a clear line of sight and scale to print those kinds of revenues on an annual basis?” When this occurs, it will be the window for an IPO. “Quite frankly Carbon and Desktop Metal are at the post-money valuation of their last trade that makes them too big and too pricey for any strategic to acquire,” he adds.

As previously highlighted, Reichental points out that the combined valuation of Carbon, Desktop Metal and Formlabs is higher than the combined value of 3D Systems, Stratasys and Materialise. “It’s an interesting dichotomy. Right? The companies that are public and have fairly significant revenue for our industry size, are valued less than the companies that are private, are in earlier stages of revenue generation, certainly in the aggregate generate revenue, but much higher as a result of the different asset classes invest in them.”

I ask if he would invest in the IPO of Desktop Metal or Carbon. He gives a diplomatic answer, “It depends on what the S-1 reveals.”

Investing with an exponential approach

Reichental has never shied away from investing, from that earlier investment in a floundering 3D Systems to his most recent venture, XponentialWorks. He describes himself as a parallel entrepreneur and explains, “I found for me the best way to harness and leverage my passions and talents and capabilities and also, my shortcomings, is to participate in multiple businesses and activities.” He enjoys, “hands-on innovation,” but also to “participate in some larger businesses in an advisory capacity. Simply because I have a lot to offer from my both private and public company experience.”

His hope is that activities such as investing and working with “really fine causes that I am passionate about and donate financial resources, human resources, volunteer time,” to means that he has “a tiny little hand in maybe leaving this universe a little better than I found it – that’s why I do it”. The “how” is “challenging and exciting”. He divides his days and weeks into sections and priorities. “I try to show up diligently to all of my activities and responsibilities.”

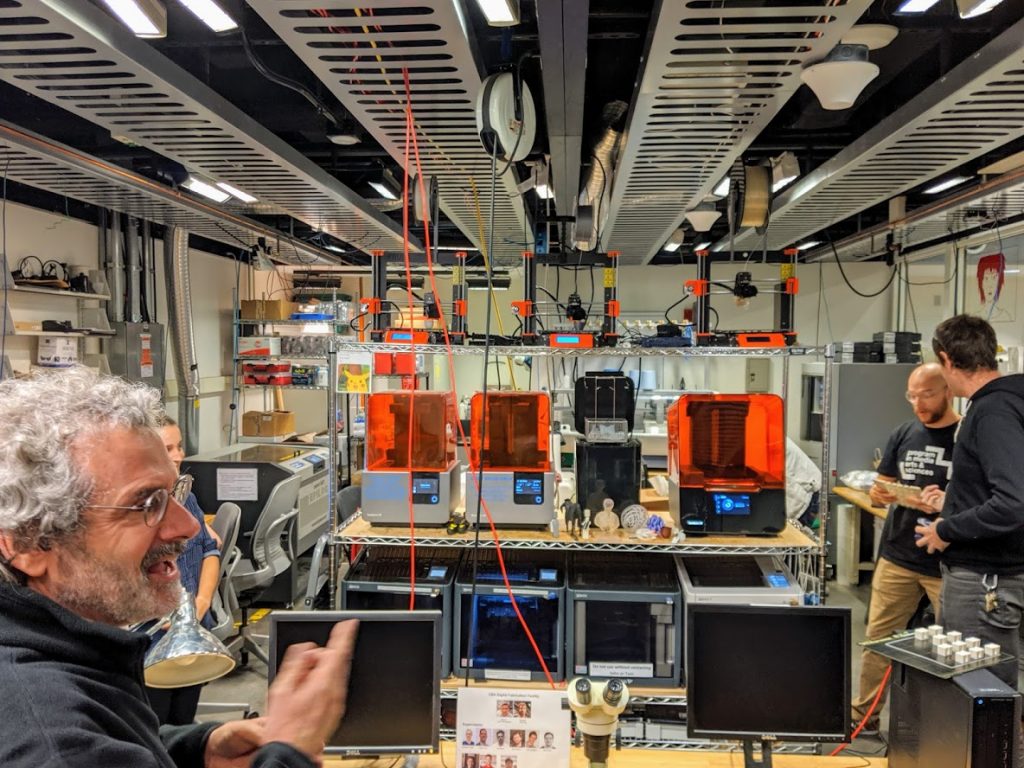

Reichental was the faculty co-chair of digital fabrication at Kurzweil’s Singularity University, and while no longer so directly involved he continues to draw from the experience. He is also very involved with Abundance 360, “one of the arms of the singularity”. Themes addressed include “the convergence of exponential technologies, the rate, and pace of disruption that these technologies can create” and how to “harvest the upside” by applying these technologies into business models. The experience was “a defining period of learning”.

His continued involvement with the X PRIZE foundation means he gets to meet, as he describes it, “Some of the most interesting and ambitious and capable people,”

“What I took from all of that is that businesses, large and small, have to go through their own exponential transformation.

“For early-stage companies that are coming into the market now it is natural to do it, because they start building their businesses by applying exponential technologies like artificial intelligence, robotics, additive manufacturing, or edge computing, etc. For more mature companies, it’s a little bit harder to do because in a mature organization there is a very strong immune system”.

This “immune system”, or institutional culture, can lead such organizations to play it safe. “It says above all do no harm, above all protect the core”. While such an ingrained response can be “extremely valuable”, it can also inhibit exponential transformation – this is where Rechiental’s XponentialWorks comes in.

“We serve as the edge organization for larger companies, creating exponential muscle and capabilities as the edge”, a technique that he believes makes it easier for companies to “transition into the core, or become a new core in a larger company”. Such capabilities have been created for EverZinc and Techniplas. Within these “edge organizations” XponentialWorks also “collides its startup companies”. “Some of the skills and muscles that larger companies need, they can learn from our startups,” he explains.

I ask what does exponential means to him. “Exponential means technologies that cause businesses to have to reinvent themselves every three to five years as opposed to every thirty years. The ability to anticipate where you would be if you took thirty exponential steps, as opposed to where you would be if you took thirty linear steps,”

“If you took thirty linear steps, you might be in the pub across the street. You’d have a pretty good idea where you’d be. If you took thirty exponential steps – the answer is about twenty-six times around the globe. Most of us are not wired to think that way.”

“Exponential to me means the ability to learn, to think and execute that way”

He paraphrases Wayne Gretzky, “this allows companies to play not for where the [ice hockey] puck is, but for where it is going to be.”

The XponentialWorks portfolio and the collider environment in action

Reichental takes me through some of the enterprises in the XponentialWorks portfolio.

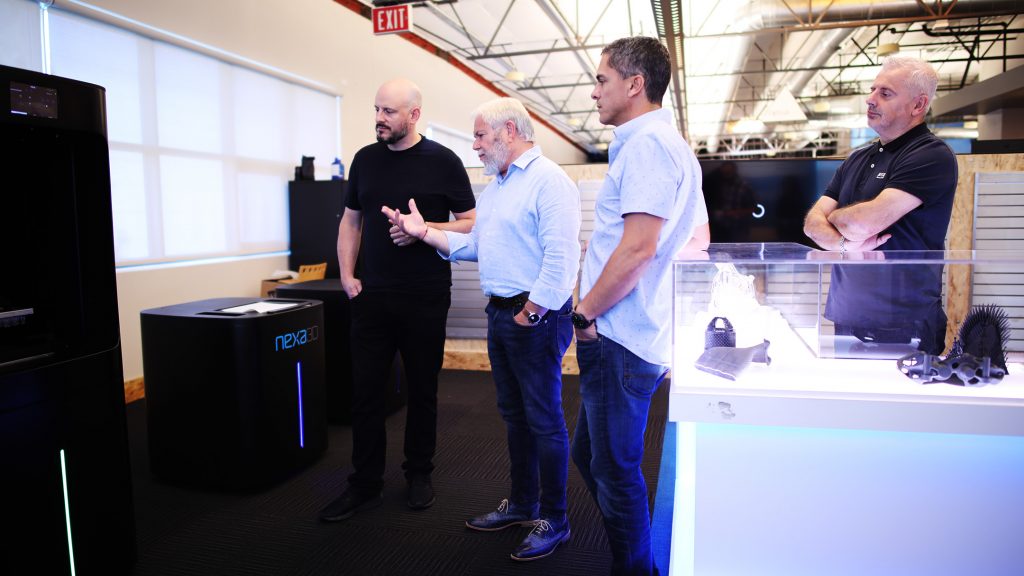

Nexa3D

“We launched the company about four years ago, we’ve tried to build a real technology based on speed. Because we believe that in this day and age, time to product and time to market is compressing. The pressure on design engineers is increasing. It’s a very finite and limited resource, the world is not inducting enough new engineers into the space.”

Nexa3D focuses “on real productivity tools,” Reichental says these, “can be a force multiplier for design and manufacturing professionals that can allow them to have something in their hands in minutes instead of hours and days is the game-changer.”

“What we did with Nexa, we decided to actually finish the development and completely derisk the product. And to derisk the market validation, before we go out and raise more money, we don’t feel that we need hundreds of millions of dollars to get to the first 50 to 100 million in revenue.”

“We need to come up with a very compelling value proposition that resonates with investors.”

This is the strategy for Nexa3D “Let’s build the printers not show the PowerPoints”

“Let’s show that we can print one centimeter in [the Z axis] per minute, but not just talk about the speed, but explain why it matters to service bureaus, design engineers and footwear manufacturers. To the best of my knowledge. There isn’t another printer on the market today that can truly deliver speed and scale with accuracy.”

NXT Factory

The question posed by NXT Factory seems straightforward, “Can we develop a high speed automated alternative to traditional SLS.” In short, Reichental wants to provide better quality than HP at a lower price. “The world didn’t need another me too system,” he says.

“SLS has the best chance to migrate into traditional manufacturing because of the part quality, the familiarity with quality supply chain approved materials by aerospace, automotive and other serious producers.” But a critical component was missing, “It lacked in downstream automation”.

“NXT Factory was founded to deliver a platform that was truly a thermoplastic conversion platform with selective laser sintering, that would be at least comparable to what HP is doing with Multi Jet Fusion.”

Furthermore, the total cost of ownership would be substantially below other AM platforms and in line with what manufacturing companies are looking for. Providing “downstream automation” and systems compatible with higher temperature materials such as PBT and PA6.

This ambitious project was chosen instead of going down a route where NXT Factory would “slug it out with everyone else” because Reichental believes “one of the biggest challenges in the additive market today is there is a lot of noise”.

While the increase in competition has somewhat served to “increase choice and democratize price point” it is “not really solving bigger challenges and advancing the technologies efficiently to the production floor,”

“With Nexa3D and NXT Factory we didn’t take on easy challenges”, if successful, Reichental expects the companies will be able to stand in the market with “not just a differentiated voice, but a compelling business proposition.”

“NXT Factory is on track to do just that” having achieved “speeds comparable to HP Multi Jet Fusion”. This goal was one of the company’s minimum value product requirements. “We can sinter PA12, PA11, PA6 and we have a system that is compatible with higher temperature materials. This is not something you find in the SLS universe today, with one notable exception in the bigger EOS system.”

The build chamber on the NXT Factory QLS systems is decoupled from the printer, so it can use an automated guided vehicle (AGV) platform to move between processing stages. “It can autonomously drive itself in and out of stations and go for controlled cooling.”

Also, a fully automated repowdering system will be introduced to fully reduce labor intensity. Reichental says that large service 3D printing service bureaus and “very large automotive companies” are “pushing for this kind of system”. “We think we package together the best of traditional SLS with higher speed and the best of Industry 4.0 applied technologies.”

Delivering by the end of 2019, the price point for a basic system and AVG enabled build chamber will be in the region of two hundred thousand dollars. “It’s about 50 percent of the new HP 5200 system.”

At this point, Avi is again keen to acknowledge the importance of very large enterprises, “HP has done a terrific job opening the traditional SLS market”. He estimates that HP has sold over 1,000 Multi Jet Fusion systems worldwide.

Supercraft3D

Supercraft3D in India “a very promising company that is in the field of surgical instruments and medical implants.”

XponentalWorks invested in Supercraft3D when it was still a concept because, “the segment from healthcare to surgical planning, medical models and implants is one of the fastest-growing and best, most suitable applications for 3D printing.” India is also one of the largest addressable markets in the world. “The company is doing very nicely going from strength to strength, developing proprietary software and workstreams.”

Nano Dimension

Reichental is the Chairman of the Board at this Israel based company focused on 3D printing electronics using the DragonFly 2020 3D printer. “The company is a first-mover in 3D printed electronics [and] printed circuit boards with the ability to encapsulate sensors and antennas to create connected devices.”

Currently, Nano Dimension is undergoing a transition from delivering its first products at the end of 2018 to building and scaling a sustainable business. “It’s still early days, but it’s very promising, very profitable,” says Reichental.

He believes there is a great opportunity for resellers to add Nano Dimension to their portfolio, as the systems are unlike other technology on the market. “We’re educating the market and creating the use cases for what we expect a greater adoption in coming years.”

He views the long-term addressable market for Nano Dimension as in the billions of dollars. Firstly in R&D, “you can find out overnight what will take you 8-12 weeks to outsource and you keep your confidential information in-house,”

“We are headed into a trillion sensors marketplace in the next few years”, as sensors are embedded in more devices. “That means more pressure on companies to electrify and sensorize their products.” The second is getting into serial production with small and medium value applications, “certainly for smaller products, there is a case for Nano Dimension to become a manufacturing platform.”

Techniplas Digital

Reichental has been the Vice Chairman of Techniplas Digital for several years. The company is a half-billion annual revenue, tier-one supplier to automotive. “As part of my responsibilities I have led the charge to help the company with digitising itself internally and creating more digital products in the future.” He summarizes this as, “basically positioning a 100-year-old traditional manufacturing business for Industry 4.0 internally and connected world externally.”

In 2017, Techniplas opened its Additive Manufacturing Center in Ventura, California. “We have the privilege to host Techniplas digital facilities here in Ventura.” Those facilities are part of the XponentialWorks collider environment

“Having companies like Techniplas resident in our ecosystem really helps us be closer to the market and put our solutions inside Techniplas factories to get instant validation and feedback. It also helps Techniplas to use Ventura as their edge organization to develop new products and capabilities without disrupting the core.”

Techniplas now has approximately 18 additive manufacturing systems, primarily for internal use. “Primarily today for jigs, fixtures, assembly gauges and end of arm attachments on robots because we have 12 factories around the world. Most of them are heavily automated.”

The large scale injection molding systems in operation at these plants are served by robotic arms that “gently grab the parts and place them where they need to be.”

“We’re working hand in hand with a few of the automotive OEM’s to facilitate the next generation of serial additive manufacturing of parts,” the names remain confidential for now. Reichental does reveal that the work involves the next generation of manufacturing platforms, which will go into production in the next couple of years.

XYZ Printing

Reichental has also worked with XYZPrinting “primarily in an advisory role and did my best to lend my industry experience as they continue to extend their portfolio and expand their geographical presence and move up the chain from entry-level systems into more professional systems.”

“Its an incredible company,” he says.

XYZ Printing is part of the New Kinpo Group, one of the largest contract manufacturing enterprises in the world after Foxconn, Flex, and Jabil. The company makes “millions of products on a monthly basis.”

“The company is legendary in Taiwan, it’s been around for over 40 years and very ably led by Simon Shen”. New Kinpo’s origins are in Cal-comp, a company manufacturing calculators and computers for many big brands. From then New Kinpo has played a role in mainstreaming many technologies ranging from home computers to 2D printers and scanners, “that’s the DNA that they bring to the table.” Through XYZ Printing will 3D printers experience a similar spread?

The combined revenue for New Kinpo Group companies was $38 billion for 2018.

“It might not be as visible as some of the 800lb gorillas in additive like HP or GE, but it’s certainly a company with long term vision, and with the resources and capabilities to be a meaningful, long term mover and shaker.”

“This is a company that knows how to do value engineering and productization, building for high value at a reasonable cost. It’s a company that has always taken the long term view

“If I was betting on companies that will be around for the long term and who would really scale and democratize 3D printing, [New Kinpo] certainly has the factories, the know-how, and the long term will to make it happen.”

UNYQ

Reichental describes himself as “more of a passive investor” in this wearables’ focused company who use 3D printing to make prosthetics.

“It represents the continuation of some of the projects that I’m passionate about, specifically democratizing prosthetic devices and robotic attachments to allow people who have an impairment to confidently go through life and regain functionality”.

The future of 3D printing

The enterprises Reichental is involved with offer a fairly comprehensive coverage of the additive manufacturing ecosystem. However, he points out there is still a significant opportunity in the sector.

“There is a great deal of work that needs to be done on the unification of the digital thread that takes the friction out of transitioning from CAD to additive manufacturing seamlessly.” ParaMatters, who started with topology optimization and lightweighting but moved into generative design, orientation optimization, and quality control is one company in the Xponential Works portfolio addressing this.

“The digital twin is of paramount importance” to connect design to manufacturing. “Simulated workflow and unified databases with the ability to end up with scalable, repeatable and verifiable serial manufacturing capabilities – that’s an area that I’m continuing to look for opportunities in.”

The other area is material innovation. “All these new platforms that are coming on stream will deal with speed, and automation.”

“In the area of materials composition, you know, the polymer science and others, there’s been a great deal of work that needs to be done to really unleash the potential”

“For many years we looked at hardware and software as constraints to further scaling and penetration in manufacturing. Now we have to take a much harder look at polymer science.” Reichental points to activity by DSM, BASF, Arkema and Henkel, “all the big players .. you name it they’re all getting excited about the space in a big way.”

“Metal is the hottest and fastest-growing opportunity in additive manufacturing,”

“In some areas like SLM you might argue there is choice overload or overcrowding. In other areas like hybridized fused deposition and jetting it’s not all that crowded.”

“Given the pent up demand and that industry understands metals more readily than plastic, this is another area of opportunity”.

Our long conversation ends on a characteristic optimistic note, “I personally believe that there has never been a better time to be in additive.”