Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) has opened a new consultation seeking advice on “Proposed regulatory changes related to personalised and 3D printed medical devices.” The call to action has been launched following a concern that current regulatory frameworks are ill-equipped to “mitigate risks to patients, and to meet requirements for health care providers and manufacturers.”

By reviewing the guidelines, and consulting medical stakeholders in consumer, health professional, laboratory professional and research capacities, the TGA hopes to “potentially re-define ‘custom-made devices'” and clarify the terms of certification where high risk 3D printed medical devices are concerned. In turn, this will help make the market for custom devices safer for patients across the nation.

Current exemptions to the rule

The TGA’s proposal highlights a loophole in current regulation that means that high risk custom devices, like 3D printed implants, can be certified in the same way as low risk devices that aren’t made to be hosted under the skin, e.g. glass eyes and prescription lenses. According to the document, “Technology has made personalised devices, including implantable devices for particular patients, within reach on a much greater

scale.”

“Consequently, ever growing numbers of patients are receiving higher risk classification medical devices to meet their particular needs, under custom made device exemptions.”

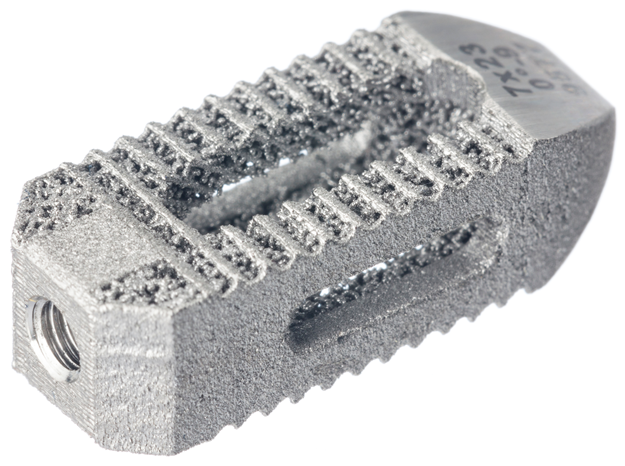

This outline does not include mass produced 3D printed devices, like Stryker’s posterior lumbar cages or SI-BONE hip implants, as the devices aren’t custom made on a patient by patient basis.

Redefining device and manufacturer

To improve the rules around the regulation, the TGA puts forward five different proposals. In two cases (Proposal 1 and Proposal 3), the TGA advocates new definitions: firstly for personalised devices and second for what constitutes a manufacturer.

Redefining the devices would mean that 3D printed implants would be excluded from the low-risk personalised device category, and instead made to comply with existing implant regulation. In the new manufacturer definition, the TGA proposes a stipulation that anyone who modifies a device already on the market would be liable for the same responsibility as an OEM.

Physical and digital conformity

Additionally, in Proposal 2, the TGA suggests “Changes to the custom made conformity

assessment procedure.” If passed, this would mean that the manufacturer’s written statement about the device is presented to the patient, rather than remaining private as in current practice.

There are also calls for “New arrangements for devices with human material” i.e. bioprinted scaffolds, and “New classification for anatomical models and

digital 3D print files,” meaning non-medical 3D files would also be subject to regulation.

Expert consultation on these proposals closes on 22 December 2017. Any interested parties can make their recommendations online here.

For more of the latest news on regulation, certification and more related to 3D printing, subscribe to our free newsletter, follow us on Twitter and like us on Facebook. Learn more about the technology at 3D printing events near you.

Featured image shows the Australian Government logo. Image via Innovation.gov.au