Researchers at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (EMPA) have used 3D printing to create a sustainable new class of supercapacitor.

The fully-3D printed battery, composed of a flexible cellulose and glycerol substrate, patterned with a conductive carbon and graphite-laden ink, is able to withstand thousands of charging cycles while maintaining its capacity. Thanks to its biodegradable base, the novel cell can also be composted once finished with, potentially making it an ideal tool for tackling the world’s electronic waste issues.

Searching for a sustainable ‘EDLC’

According to the EMPA scientists, the recent boom in electronic wearables, packaging and Internet of Things (IoT) applications, has seen the global number of these devices rise to 27 billion. However, given their short life cycle, and the fact they tend to be powered by non-renewable lithium ion or alkaline cells, many such products will eventually be landfilled, worsening the global ‘e-waste’ problem.

In an effort to develop more eco-friendly energy storage devices, scientists have therefore begun to experiment with electrical double layer capacitors, or ‘EDLCs.’ These high-capacity, fast-charging supercapacitors can at least partially be manufactured from biodegradable materials, potentially making them an ideal replacement for normal batteries, which often require specialized disposal services.

Although a significant amount of research has gone into EDLC R&D, their varying parts such as electrodes and current collectors, can be difficult to produce via a single manufacturing process. What’s more, many prototype EDLCs are partially-3D printed at most, necessitating their time-consuming and expensive assembly or post-processing, which make them unattractive as commercial ventures.

A ‘state-of-the-art’ supercapacitor

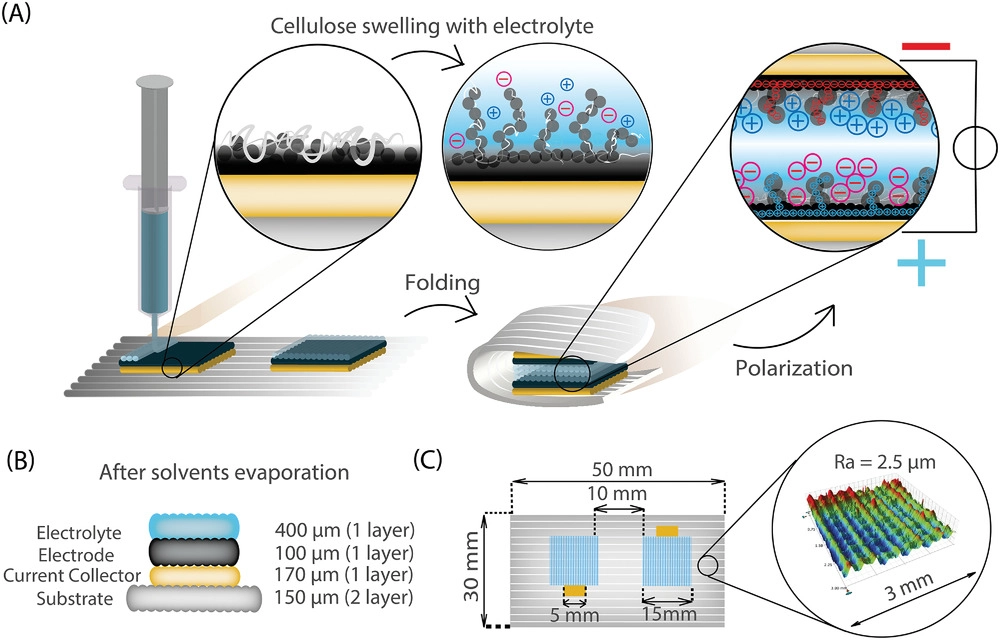

To streamline EDLC production and create an eco-friendly battery of their own, the EMPA team turned to DIW 3D printing, which they used to manufacture two half cells before folding them together. In practise, this meant printing the unit’s substrate base first, then depositing its electrode and conductive graphite-infused electrolyte layers on top, in a process that after some tweaking, yielded a functional battery.

“It sounds quite simple, but it wasn’t at all,” said Xavier Aeby of EMPA’s Cellulose & Wood Materials lab. “It took an extended series of tests until all the parameters were right, until all the components flowed reliably from the printer and the capacitor worked.” He added, “As researchers, we don’t want to just fiddle about, we also want to understand what’s happening inside our materials.”

Once their supercapacitor prototype was ready, the scientists sought to test its charge retention by charging it to 0.5 V, before measuring its open surface voltage. According to the researchers, their device still had 30% of its charge remaining after 150 hours, putting its performance “in-line with that of state-of-the-art carbon-based supercapacitors.”

Interestingly, the researchers found that the capacity of their supercapacitor also fluctuated for two weeks after fabrication then settled, while it later remained functional after eight months in storage, and when they had finished their experiments and attempted to compost it, they were able to dissolve around 50% of its mass over the course of nine weeks.

During testing, the team’s device was ultimately capable of powering a 3V alarm clock under mechanical stress, as well as operating at wildly varying temperatures. As a result, with further R&D, they say it could be deployed on a wider scale, to sustainably power low-voltage smart devices such as those used within environmental monitoring, e-textiles or healthcare applications.

Printed batteries: ready for market?

While 3D printed batteries remain at a relatively early stage of development, there are promising signs that the technology is progressing towards being end-use ready. Previously known as KeraCel, the rebranded Sakuu Corporation has recently announced plans to launch its first solid state battery (SSB) 3D printer in 2022, which is said to yield cells with a much higher capacity than current Li-ion devices.

In the UK, 3D printer manufacturer Photocentric has established an internal battery R&D division, in which it is attempting to design a new energy-efficient storage device of its own. By reducing the size and weight of battery electrodes, the firm ultimately aims to develop a unit that’s better suited to automotive applications, and it is said to be targeting an upcoming Tesla Giga factory with its creation.

In similar, albeit more experimental research, a team at the University of Manchester have developed a 3D printable ‘MXene’ ink, and used it to produce prototype supercapacitors. During testing, the scientists said that their additive manufactured electrodes demonstrated both the high capacitance and energy density needed to power the cars or mobile phones of the future.

The researchers’ findings are detailed in their paper titled “Fully 3D Printed and Disposable Paper Supercapacitors,” which was co-authored by Xavier Aeby, Alexandre Poulin, Gilberto Siqueira, Michael K. Hausmann and Gustav Nyström.

To stay up to date with the latest 3D printing news, don’t forget to subscribe to the 3D Printing Industry newsletter or follow us on Twitter or liking our page on Facebook.

For a deeper dive into additive manufacturing, you can now subscribe to our Youtube channel, featuring discussion, debriefs, and shots of 3D printing in-action.

Are you looking for a job in the additive manufacturing industry? Visit 3D Printing Jobs for a selection of roles in the industry.

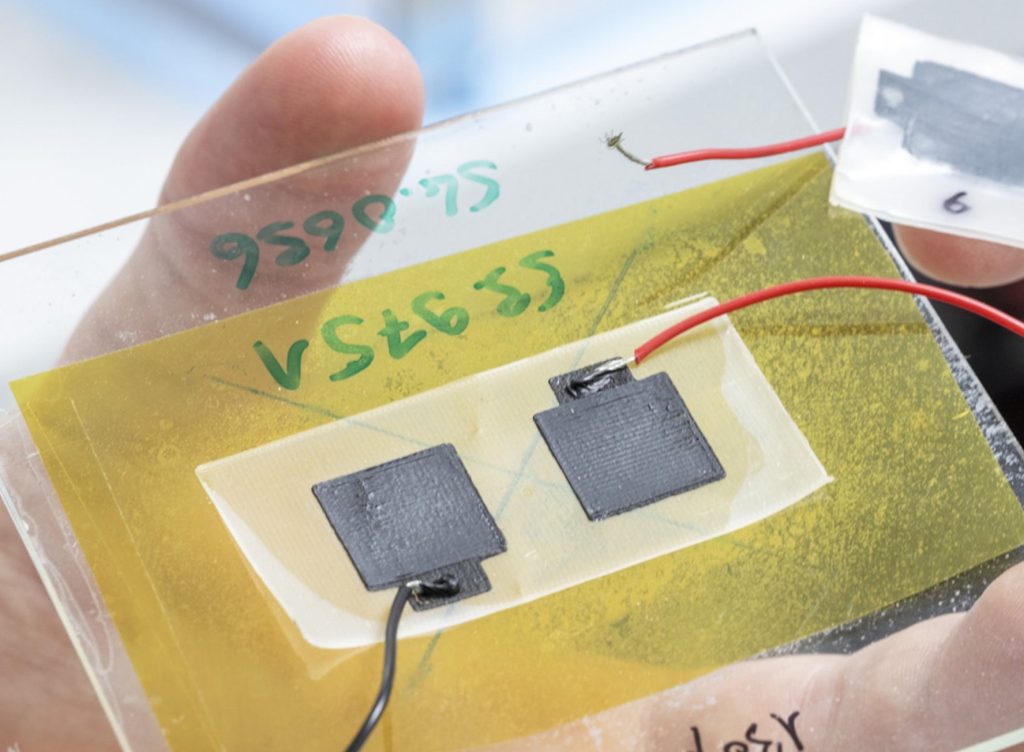

Featured image shows the the EMPA researchers’ 3D printed supercapacitor. Photo via EMPA.