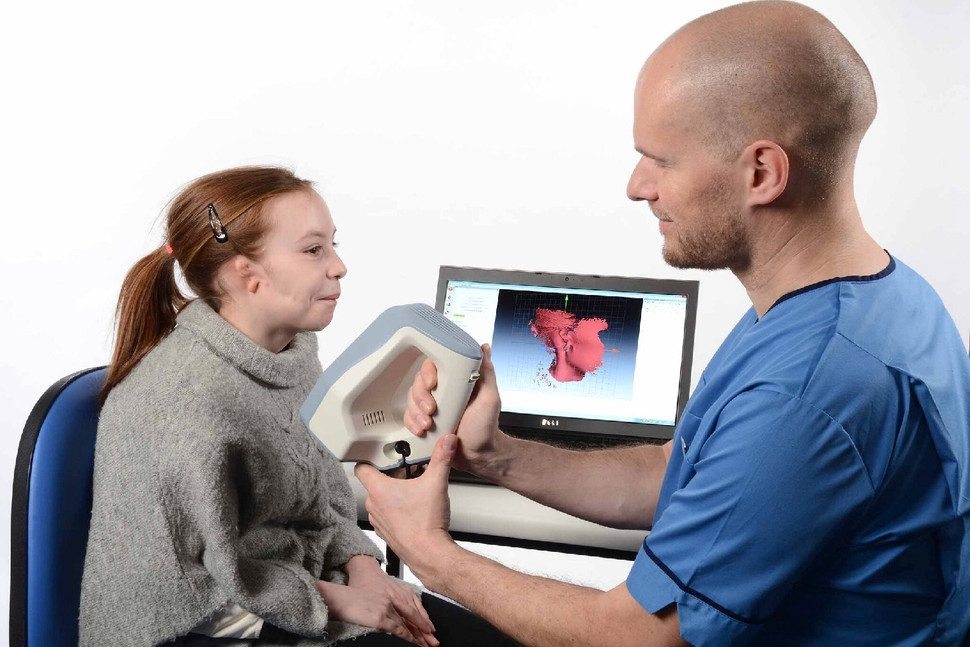

Dr Ken Stewart, from the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh, has adopted 3D scanning technology to produce lifelike ears for children born with Microtia.

It affects one in 10,000 children and it manifests itself in an underdeveloped pinna. Effectively this means they are born with no real outer ear structure and plastic surgeons have been fighting with this condition for decades.

Tracing the healthy ear

Most Microtia sufferers have one healthy ear, so an older technique involved using an acetate sheet to take a tracing of the complete ear and using this as a template for the mirror image. Inevitably, this did not produce perfect results.

MRI scans replaced the acetate sheets, but even that did not get the best results and the MRI scan itself is an expensive procedure. So Dr Stewart might be on to a winner with the handheld Artec Spider 3D scanner.

“Most patients are born with one ear missing or a loose part of one ear,” Stewart tells Digital Trends. “Traditionally we would use a clear acetate to take a 2D tracing of the normal ear. This would be used as a template to help carve an appropriately sized and shaped opposite ear. The 3D scanner and mirror image software allows us to produce a more accurate template.”

Spider’s price does not bite

It is still not a cheap scanner and the latest version retails for $27,600. But with each MRI scan costing an average of $2,611, this handheld scanner becomes a relative bargain.

The price of MRI scans is coming down, too, and they are not used regularly before major operations. For specific tasks like creating a new ear, though, a handheld scanner with its own suite of software offers comparable results for a much lower price. Others scanners as the Einscan Pro can do the same for $4,099 at iMakr.

Stewart still prefers to produce the new ear from extracted rib cartilage under the patient’s own skin. Other treatments include plastic implants inside the patient’s skin and complete prosthetics that can be permanently grafted to the skin.

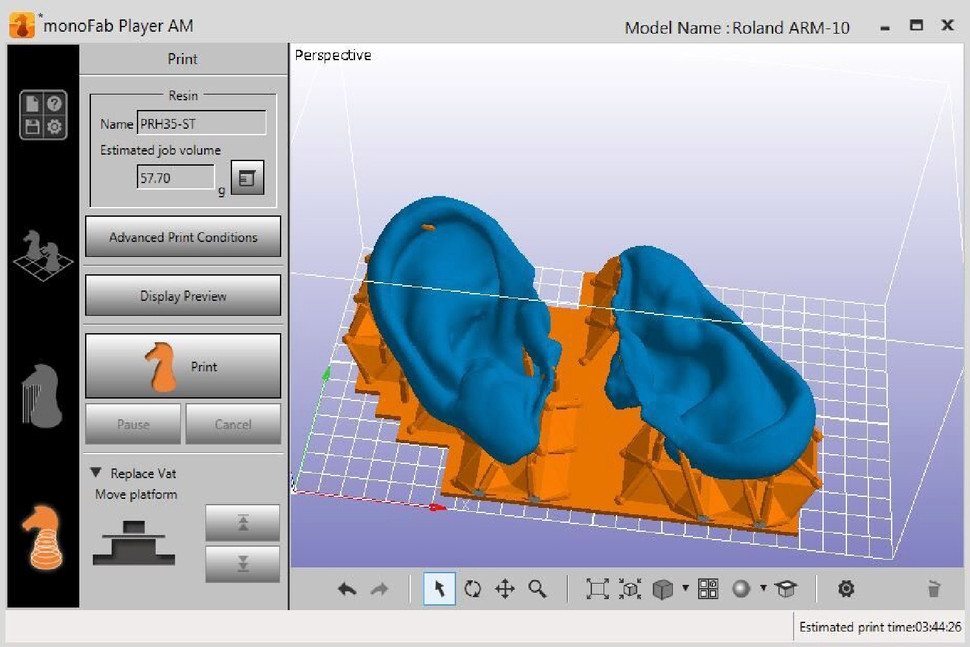

Now, Stewart takes his scan and uses a 3D printer to create a replica of the ear. That then gives him a precise guide to work from when he uses his preferred technique. The models are simply printed plastic guides right now, but Stewart thinks that won’t be the case for much longer.

Bioprinted ears are on the way

He believes we’re not far away from replacement ears created from polymers and stem cells.

Stewart said: “We are working with scientists at Edinburgh University’s Centre for Regenerative Medicine and Chemistry Department with a view to tissue engineering an ear. Professor Bruno Peault and his team have characterized stem cells within human fat which lie next to blood vessels. We can harvest these very easily by liposuction.

“For a plastic surgeon that is easier than taking blood. With Professor Mark Bradley’s team in the chemistry department we have identified FDA approved polymers to which the stem cells will bind and can be driven to produce cartilage. We know we can 3D print in the polymers concerned. So the Artec-derived 3D scans could potentially be mirrored and 3D printed with the ideal polymer.”

It’s just one more way that 3D scanning and printing have combined to lower the costs of complex medical procedures and improve the quality of life of children that were born with a cruel disfigurement. We can’t wait to see what comes next.