New research into 3D printed medicine has shown – for the first time – that a combination of inkjet printing and UV curing can produce, “solid oral dosage forms” of drugs.

The research opens the door for personalized medicine, improvements in small scale clinical trials and “functionally graded dosage design.”

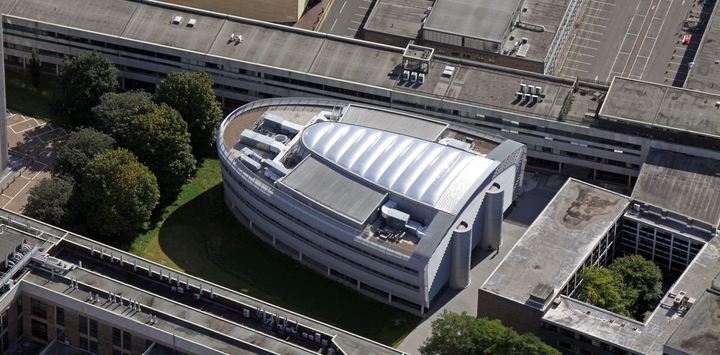

University of Nottingham scientists working with pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) conducted the study “3D Printing of Tablets Using Inkjet with UV Photoinitiation.”

Martin Wallace, GSK’s director of technology, is one of the named authors on the research paper. In an earlier interview Wallace told me how “Printing tailored medicine could simplify our supply chain dramatically.” Other reasons for 3D printing pharmaceuticals include modification of the tablets geometry to change drug loading, to alter the release profile or even to disguise an drug’s taste.

Epilepsy drug Spritam was the first 3D printed medicine to receive FDA clearance. More recently the European Medicines Agency (EMA) cleared Janssen to produce Prezista, an HIV drug, with a continuous manufacturing process. Continuous manufacturing allows drug companies to make smaller volumes of medicines, reducing inventory and responding to demand. While 3D printed medicine is at an early stage, it may eventually form part of such a system.

Batches of 25 pills were 3D printed using a specially formulated ink containing Ropinirole HCl, a medicine used for the treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS) and Parkinson’s disease.

Inkjet 3D printing offers potential to scale

The researchers highlight inkjet 3D printing for its, “precision, accuracy, low cost, ability to deposit multiple materials contemporaneously and simple scale up/out.” These are the same advantages of inkjet 3D printing that make this brand of additive manufacturing a prime candidate for widespread adoption.

Inkjet is a well understood technology, with enterprises such as HP using 2D inkjet printers like the vast HP PageWide T1100S Press – a machine capable of printing up to 600 ft/min (183 m/min) with a printable width of up to 2.8 meters.

Now while HP’s inkjet web presses are currently 2D, they are based upon piezo-ceramic inkjet technology, albeit with slightly larger print bars. If 3D printing is going to challenge current pharmaceutical production volumes of 1.6 million tablets per hour, then inkjet would seem the approach to take.

The paper reviews recent approaches to 3D printing medicine, noting that the, “doses produced are films, often with an edible substrate incorporated into the dosage form.” This means the solvent must be evaporated or a cooling stage is required to solidify the dose.

Combining 3D inkjet based printing with UV curing is advantageous because this process can, “build scaffolds and complex (torus) tablet geometries with extended release profiles at ambient temperature.”

How to 3D print pharmaceuticals

The study used a Dimatix Materials Printer DMP-2850, a machine prefered for lab work given the low volume 1.5ml cartridges. These minimise the quantity of material required for an experiment. The printer was modified with a purpose built glove box to allow control over oxygen levels – which in turn can be used to control the photopolymerization process.

Additionally an LED UV lamp was bolted directly onto the printhead. Readers interesting in following the ink formulation method can find full details in the paper.

Using this set-up, batches of 25 tablets with a 5mm diameter were produced. Total printing time was 1.5 hours or approximately 4 minutes per tablet. Curing time was an additional 7.5 minutes per batch.

The researchers conclude that, “UV inkjet printing has been demonstrated as a platform to produce solid oral dosage forms for the first time.”

Testing with Raman mapping, FTIR-ATR and optical microscopy demonstrated that the 3D printed pills had “amorphous solid dispersions with high degrees of photopolymer curing”.

Elizabeth A. Clark, Morgan R. Alexander, Derek J. Irvine, Clive J. Roberts, Martin J. Wallace, Sonja Sharpe, Jae Yoo, Richard J.M. Hague, Chris J. Tuck and Ricky D. Wildman conducted the research “3D Printing of Tablets Using Inkjet with UV Photoinitiation.”

For all the latest news about scientific advances using 3D printing, subscribe to our newsletter and follow our social media accounts.