Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) is frequently covered by 3D Printing Industry. We’ve reported on projects such as the first 3D printed submarine hull, record-breaking BAAM machines and even a drug-sniffing 3D printed moth.

I spoke to Dr. Niyanth Sridharan – a Postdoctoral researcher in the Material Science and Technology Division at Oak Ridge National Laboratory – to learn more about what it is like to work at the lab, and also about two recent projects using additive manufacturing.

Dr. Sridharan joined ORNL as a postdoc and is currently working his way up the “food chain”. Recently he has worked as project lead, investigating how diesel engines can be refurbished with additive manufacturing and also in a group looking at how Ultrasonic Additive Manufacturing can be used to make nuclear reactor components.

Repairing engines with additive manufacturing

The Cummins Inc project, addresses the problem of how to extend the life of an engine. The cast iron engines are used by freight trucks might be good for tens of thousands of miles of haulage, however eventually fatigue will set in. When this happens cracks can begin to appear in engine.

Dr. Sridharan explains, “Instead of throwing all existing engines at the end of their life-cycle the company wanted to find a way to refurbish such engines.”

With this in mind, the process developed at DOE’s Manufacturing Demonstration Facility at ORNL, plans to save energy while extending the life of the engine and making it stronger.

“When Cummins gives us the worn out engine blocks, with the location of the cracking identified we machine down the cracks. It’s like scooping out the cracked portion and then we can go in and rebuild using 3D printing.

We deposit a nickel based material that has a higher thermal conductivity and this improves the overall efficiency and performance of the diesel engine.”

The nickel-based material was slightly modified to make it more resistant to cracking after a, “substantial amount of computational work and simulation”. This work was performed to understand the residual stresses calculation and understanding how heating and cooling with additive manufacturing will affect the cast iron.

To repair the engine ORNL use a blown-powder additive manufacturing technique. Specifically a machine manufactured by Michigan based DM3D.

“Typically the system permits material deposition of 10 to 15 grams of material per minute,” says Dr. Sridharan.

Additive manufacturing cuts across many disciplines, and projects can involve mathematicians, robotics specialists, materials experts and more.

3D printing with sound to make nuclear components

In addition to investigating applications for blown powder additive manufacturing Dr. Sridharan is also working on a project looking at Ultrasonic Additive Manufacturing (UAM).

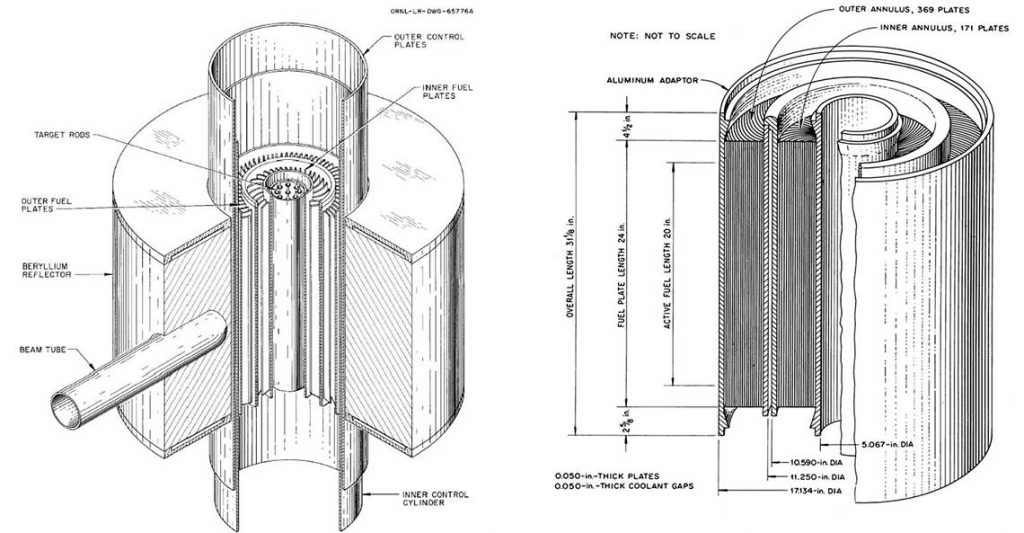

“I work very closely with Fabrisonic. It’s very exciting because there are a bunch of people with diverse backgrounds who have come together at Oak Ridge and we have demonstrated that we can actually use Ultrasonic Additive Manufacturing to facilitate fabrication of control plates for the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR)”

Ultrasonic Additive Manufacturing uses uses sound to merge layers of metal drawn from featureless foil stock. Mark Norfolk, President of Fabrisonic, recently told us more about how Ultrasonic Additive Manufacturing works.

The control plates in the HFIR are described as “two thin, poison-bearing concentric cylinders.” These “are located in an annular region between the outer fuel element and the beryllium reflector.”

Working on the HFIR UAM project were, “A mass of people. People from materials, nuclear, computation, mechanical testing, additive manufacturing all working together.”

The project has just ended and “demonstrated that we can use UAM to make these control plates for a nuclear reactor,” says Dr. Sridharan.

As mentioned, ORNL is often featured by 3D Printing Industry and as Dr. Sridharan explains, “Even as a junior researcher I am very excited to work here because it brings together people with such a diverse background.”

Additive manufacturing is increasing receiving validation as an important tool for the energy sector. You can read more about this topic here.

For more insights into the latest additive manufacturing research, subscribe to the most widely read newsletter in the 3D printing industry, follow us on twitter and like us on Facebook.

Featured image shows inside the ORNL High Flux Istope Reactor. Photo via ORNL