Xjet received as “unprecedented level of interest” after revealing a new 3D printing method at RAPID 2016. I caught up with Dror Danai, Xjet CBO, as he prepared to return to Israel’s inkjet valley.

Danai is a 3D printing veteran and our conversation is punctuated with snatches of 3D printing history alongside in depth knowledge: always expressed in a charming manner. In this interview Danai explains the capabilities of the forthcoming machine and the technology developed by Xjet.

Rare Method

Invention and innovation, two similar words but with subtle differences. Invention can, arguably, be represented by the award of a patent while innovation requires another step: making use of the invention.

3D printing companies are frequent innovators and applications regularly garner the oft-bestowed, and oft-inaccurate, label of disruptive technology.

Less frequently, new 3D printing methods appear. The team behind Xjet is pioneering a one of these rare methods, a technique to print metal using inkjet heads.

A lot of people have tried this over the last 20-30 years: to melt the metal and then jet it, the problem with metal is that it’s a very aggressive material. So the metal hurts the nozzle and what happens is that it doesn’t work

Traditional metal 3D printing techniques work with “a source of energy that brings the metal towards a melting point.” Xjet’s technique in different “we don’t do that, we never melt the metal,” says Danai.

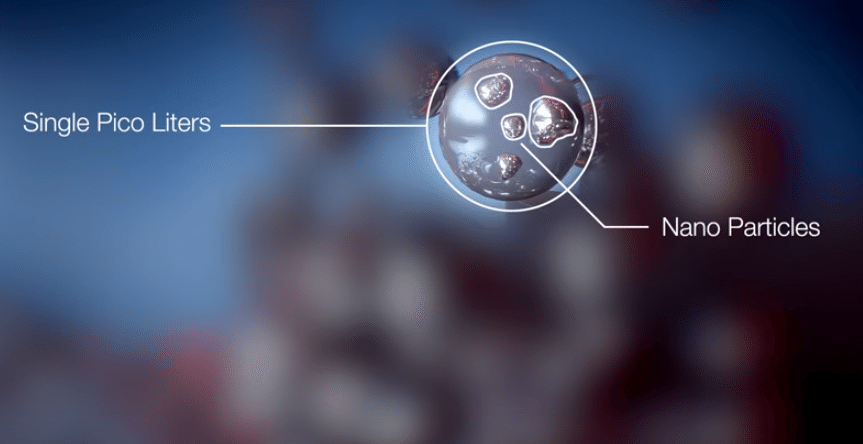

Instead “we take metal into a nano-particle form and then we suspend it in a unique liquid.” Xjet call this technology NanoParticle Jetting (NPJ) and are redefining 3D printing: starting with the term itself. In Xjet lingo, 3D printing’s three ‘Ds’ represent, details, dispersion and design freedom.

The liquid forms a jacket around the particles of metal and in the printers build envelope, at temperatures up to 550Fº (300Cº), evaporates. In comparison steel melts at a temperature about four and a half times that figure.

Every single particle is surrounded by this oily like material that allows us to jet it in a standard inkjet technology. At this temperature the carrier, the liquid, almost completely evaporates when it touches the tray. Now the beauty is that there is almost a microsecond in which before it evaporates its still in liquid form for a very short time. This means that we create a perfect packing, so we have no porosity at all.

This is a bold statement and the porosity question is one that continues to challenge some of the brightest minds in 3D printing. Empty spaces or voids in can decrease component strength; shower curtains provide a way to understand the cause.

In terms of repeatability, porosity and the complex algorithms going into working out the best build conditions, it sounds like Xjet have completely side-stepped these issues by using inkjet. Danai says “we bypass the issue of stress.”

Fluid dynamics in the bathroom

Meltpools in laser and electron beam based 3D printing methods have to contend with the Bernoulli effect. The high temperatures, approaching 1800ºF (1000ºC), create their own weather system in the build chamber.

In the same way a shower curtain is pulled towards the leg of the bather by fluid dynamics, metal powder can be pulled back into the meltpool by similar forces. These partially melted particles diminish structural integrity.

Xjet have, “more than 12 thousand nozzles jetting down.” The metal nano-particles are randomly distributed within their oily jackets and when freed from the jacket the liquid metal blends together. Much like the relentless T-1000, or a snowflake returning to water.

The resulting 3D printed object must then be sintered in a furnace. The green part is “breakable, but not easily.” Furthermore, sintering the complete component “guarantees uniformity in all directions, because it’s sintered as one piece rather than traditional technologies that work one layer at a time.”

This material that we use for support, support is jetted in exactly the same way, we blend the nano-particles but there is one major difference, it doesn’t sinter in the oven. Actually in the oven it turns into a powder, so it’s almost removed. This takes away a lot of the challenge [of post processing] and makes things easier.

The approach brings numerous other advantages. Layer resolution is at the micron level “we’re below 2 microns” but this is “still a moving target.” Danai says XJet are “testing anything between 125 to 260 μm.”

By comparison a sheet of paper can reach 180 μm and a human hair 200 μm. Danai will not be drawn on what this means for control of the microstructure and the possibility to create materials with a novel Young’s Modulus.

But in terms of material usage he sees a clear advantage. An industrial powder bed 3D printer can require several kilos to fill the bed. While Xjet machines only jet material that is used meaning “it will be cheaper, but not drastically.” Clean-up and post processing are also simplified.

Feedback from potential customers around materials handling was unexpected and “an outcome of our choice to be liquid based” but “was not strategically planned.” Powder based systems can be messy “people told me your great advantage is that it is so simple because of the cartridges” which are sealed. “Nothing is in touch with the customers, so there is no inhaling problem,” adds Danai.

As Xjet continues to run through development cycles and refines optimal parameters for the machine another advantage has become apparent. “We take students from the university and train them in the morning and in the evening they can start running the machine.”

Will this be Yuge?

CEO and CTO Hanan Gothait founded Xjet in 2005 after his previous 3D printing enterprise, Objet, was acquired by Stratasys. But the company is not alone in their bid to become 3D printing pioneers: even in the small town of Rehovot. Twenty miles south of Tel Aviv and seven and half thousand east of Palo Alto, Israel’s 3D printing cluster is not immune to disputes over the poaching of ideas, nor of high value individuals.

Together with Gothait, in 2000 Danai “launched the first Objet machine and then the second generation in 2003.” Xjet’s NPJ will be available early next year, after 10 years in development.

The caliber of the team is illustrated by the fact that even with several patents to his name Danai is “not even in the lab, I’m lucky to be talking to customers for the most part of my day.”

He is proud of the team. “I wouldn’t say the best in the world but they are definitely the best in the country!“ With more than 50 patents shared among the group this is a reasonable statement.

An intriguing factor in all this is that when striving to make smaller parts, 3D printers balloon in size.

While the intricately detailed high-resolution prints might give even Trump’s hands the semblance of a titan, make no mistake “It’s a heavy metal machine!” This is “a 5000 lb printer and its 10 foot long,” says Danai.

When you look at it, it looks gigantic! On the other hand when you start to become friendly with it and more intimate, it’s a lot of fun. It’s a touch screen, it’s a lot easier than running a powerpoint presentation or an application on your iPhone.

All this lends credence to Warren Bennis’ prescient proclamation that notwithstanding a need to hunt pokemon or draft a swift pitch deck,

The factory of the future will have only two employees, a man and a dog. The man will be there to feed the dog. The dog will be there to keep the man from touching the equipment.

Materials close-up

Materials are one of the most exciting areas in 3D printing, and much like the manufacturing technologies that came before are an area where progress can be slow: especially in an era where software companies have come to epitomize progress.

“One of the reasons that it took so long to develop the technology is because there are no textbooks,” covering Xjet’s nano-particle ink and “nobody really did it in the order of magnitude that we’re talking about.”

Even when pressed Danai will not go into specifics about how the nano-inks are produced but tells me, “we use some of the world’s best experts.” As mentioned, these experts have approximately 50 patents to their names.

However, a recently published patent describes “glycol ethers, and water soluble liquids such as ethylene glycol, propylene glycol” as examples of the carrier ink, or jacket. This may give inquistive minds some indication of what is to come.

In that particular patent the ink is described as a Tungsten-Carbide/Cobalt ink. Tungsten-Carbide can be used to make superior grade surgical instruments and its resistance to scratching makes it a popular choice for a wedding band.

Danai tells me early uses of the machines may well involve “medical instruments because of short runs, high quality” and “they need quick turnaround and complex geometries.”

Xjet will “launch with a single metal” but have an eye on the future.

Digital alloys and metals on the fly

In the long term Xjet have three routes to explore. In terms of platform, inkjet will serve the company for the next five years at a minimum, future advances will be an “engineering challenge and not a technology challenge.” As the company grows, the second route of materials becomes even more interesting. Xjet plan to develop the capability to bring materials to market at a faster speed, and not just with metals.

Finally, and perhaps most excitingly, there is the application path. Although it is early days Danai hints at the potential for “digital alloys.” Control of the microstructure sufficient to “create metals on the fly” or “create totally new alloys.” However, he is keen to focus on the launch of the printer rather than indulge in crystal ball gazing.

This not Danai’s first rodeo. He has already guided several 3D printing ventures to market. “All of them were very successful eventually but it was very hard, it was never easy,” he says.

Getting to see the Xjet’s NPJ tech in action might also be a difficult task, but if this article has piqued your interest the company will be at FormNext Frankfurt in November.