The Scan the World project has achieved another 3D printing landmark in the cultural heritage projects short history.

Founded by Jonathan Beck, Scan the World uses a range of 3D scanning techniques to capture art from across the globe. Once digitized, the scans are made available for free and are widely used by educators, the 3D printing community and other artists.

It is highly likely that visitors to any 3D printing show in the past couple of years will have seen 3D prints from the Scan the World collection. Last week Scan the World added the 10,000th 3D scan to their rapidly growing archive.

I caught up with Jonathan Beck to learn more about how the project has developed, and what is next for the world’s largest collection of 3D printable art.

3D Printing Industry: Congratulations on reaching this landmark of 10,000 scanned objects.

Jonathan Beck: Thank you! And many thanks to the whole 3DPI team for your support in documenting the project’s progress over the past year.

3DPI: How did you reach this number?

JB: Collecting 10,000 sculptures is obviously no easy feat, and an archive of this calibre would have not been possible without the support from a dedicated community helping to build and maintain it.

When I first started the initiative in 2014, my first few hundred sculptures were scanned as part of a series of ‘scanathons’ I undertook with friends and other photography enthusiasts. We’d choose a victim institution in London, such as The Victoria and Albert Museum or The British Museum, and teach each other the process of photogrammetry. Once set up, we’d let loose on the collections as to gather as many scans as we could. From thereon it was a lot of guerrilla scanning; a commission from an artist in Paris led to me scanning the entire collection of the RMN’s cast foundry without them noticing, and then The Louvre under the noses of security guards, and so on.

This continued until the project was picked up by The V&A who invited us to exhibit in ‘A World of Fragile Parts’ at La Biennale di Venezia. Since then we have struck up a series of collaborations with institutions in running various workshops and scanning trips, employing the use of a structured light scanner to start digitizing faster and at a much more reliable quality. This doesn’t mean we don’t use or accept photogrammetry scans from the community, we’re constantly encouraging people to venture out and take some pictures!

3DPI: How is the 3D printing community using the models from Scan the World?

JB: I’m honestly always surprised as to where the models end up. Every model is 3D printable, which I believe is as important as making the data free to access and suitably archived, so MyMiniFactory’s maker community is constantly very busy with producing some incredible prints.

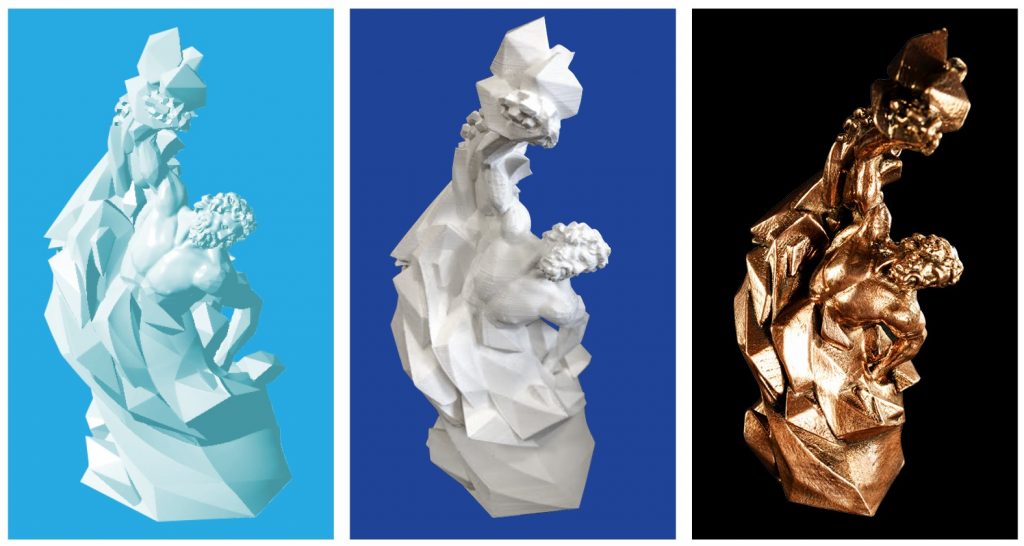

I’ve seen some wonderful initiatives making great use of the objects, from printing the sculptures in classrooms to someone making a fireplace out of a compilation of various scans. Laocoon and His Sons has also seen his fair share of action, aside from being CNC milled for a Mardi Gras float, he was also the result of a successful competition hosted by MyMiniFactory and Virtual Foundry for the 3D Printing Industry Awards, the remixed model by Printed Obsession can be downloaded here.

Printing aside, earlier in the year I was introduced to The VR Museum of Fine Art, a VR experience built by Finn Sinclair using models from Scan the World. Various render artists have been creating some glorious reinterpretations of the archive, such as Caz Egelie’s playful take on user experiences in the museum of the future and Ratatat throwing sculptures at each other as part of their live show VFX in 2016.

3DPI: What has been the reaction from traditional art institutions?

JB: It always depends on how the institution approaches the philosophy of their collection, so the reaction is either fear and loathing or open-arms and general excitement. Many traditional museums have specific approaches to licensing so those who still charge academics ~£100 to access a jpeg are bound to be stunned when they learn that their 3D collections have been covertly scanned, 3D printed and made open access.

Other museums, such as The Statens Museum for Kunst, Metropolitan Museum of Art and Musée Saint-Raymond are embracing the OpenGLAM (Open Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums) movement, opening their data to embrace and inspire a digital generation to share common knowledge and reinterpretations of culture. These institutions have found a more diverse audience engaging with their collections and a varied footfall entering through their doors. It’s only a matter of time that more institutions will follow suit, and Scan the World is a free service to support them in all aspects of 3D technologies and digital strategy.

3DPI: What are some of your favourite scans from the first 10,000 and why?

JB: Everyone’s favourite Bust of Nefertiti, a high-precision scan released open source by artists Nora Al Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles. This story has become a defining moment in object ownership in the digital age.

The Arch of Triumph, a Roman ornamental archway destroyed by human conflict in Palmyra, was reconstructed, fabricated and toured across the world. When it was unveiled in Trafalgar Square, knowing the organization behind the project had no intention in sharing the model, we scanned and shared it ourselves.

3DPI: Have you been surprised by how the project has developed? How has it changed from your original vision?

JB: Absolutely. Although nothing has changed from my original vision, which has both been to focus on the democratization and dissemination of culture using accessible 3D technologies as well as to encourage a community to disrupt institutions to obtain information about culture and heritage. I’m constantly reminded of what this means on a broader scale, from creating a whole new museum experience for someone who is visually impaired to creating blueprints of objects which, either due to human conflict or natural phenomena, do not exist anymore.

I was certainly not expecting to have produced so many models, nor that Scan the World would become the thriving platform that it has become today.

3DPI: What is next for the Scan the World project in 2018?

JB: Although we’ve just hit a major milestone we have no plans of slowing down and it’s already evident that 2018 is shaping up to be a successful year. I will be touring different institutions over the course of the year, working with various departments in digitizing and fabricating their collections, continuing to push for the data to be released as open as possible.

Traveling aside we have plans to augment the platform’s user interface, making it a lot easier to find even the most obscure object within the archive. This will include a clearer link to tutorials and a space for the community to share both their scans and their prints, remixes and works!

3DPI: How can people get involved in Scan the World?

JB: Scan the World is still very much community driven and there are countless ways of getting involved. Whether you own a professional 3D scanner or just want to get started with your smartphone (see this very handy, albeit dated tutorial) there is a means of contributing to the archive.

As well as this, because all of the data is accessible I invite any 3D enthusiast to make their own mark on the collection and sharing it with us through the website. The models are all guaranteed 3D printable and are all available on MyMiniFactory’s click-and-print feature, meaning you can print any of the models at the click of a button. Be sure to share your works with us through the website, Twitter or Instagram.

Our goal is to upload 20,000 sculptures to the platform next year, so if you would like to support Scan the World’s efforts you can do so through contributing through a subscription basis.

Nominations for the second annual 3D Printing Industry Awards are now open. Let us know if Scan the World is one the most important 3D Scanning projects of the year by making your nomination here.

For more information on 3D materials, subscribe to our free 3D Printing Industry newsletter, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.

Featured image shows the The V&A Scanathon. Photo via Scan the World.