This is a guest post in our series looking at the future of 3D Printing. To celebrate 5 years of reporting on the 3D printing industry, we’ve invited industry leaders and 3D printing experts to give us their perspective and predictions for the next 5 years and insight into trends in additive manufacturing.

Dr Matthew Partridge is a research fellow within the Center of Engineering Photonics at Cranfield University in the UK. His primary research area is in fiber optic chemical sensors that are used for inspecting conditions in substances and even in patient diagnostics. As previously reported on 3D Printing Industry, some of his research helps to promote the study of microfluidics through 3D printing.

3D Printing The Next Five Years by Dr. Matthew Partridge, Research Fellow at Cranfield University

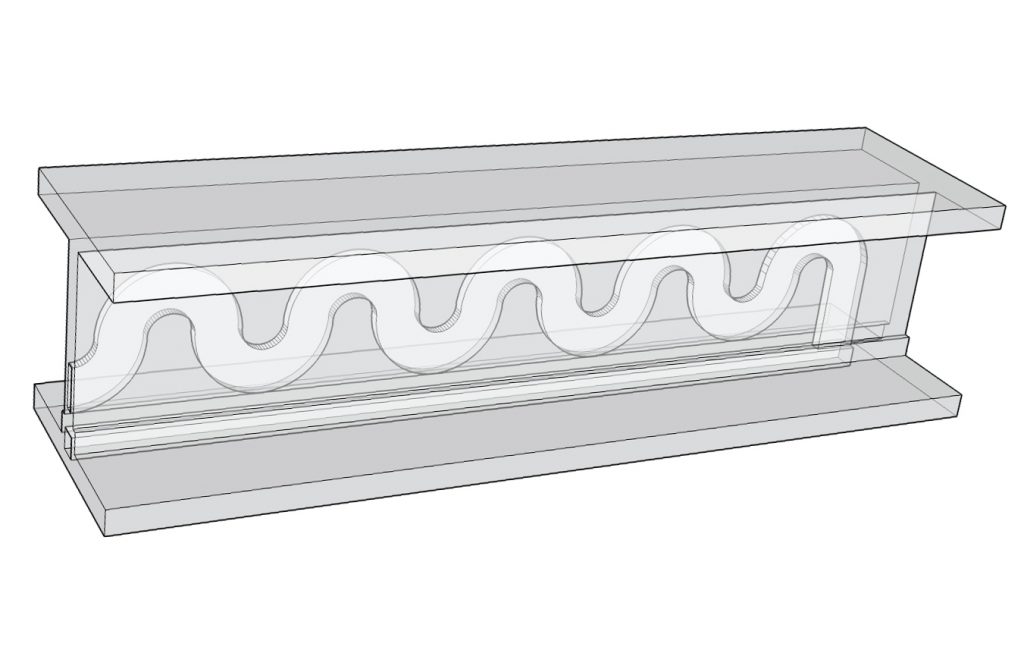

We bought our first 3D printer a little under three a years ago. It was part of a project to make a sensor that needed to be held inside a flow tube, so I used the argument of a complicated diagram and the words “3D printer” flashing on a slide to convince the powers-that-be to spend some grant money on one. In reality I, like most people, was just amazed at all the things 3D printers seemed to make and jumped at an opportunity to play with one.

Like all research grants, the budget was limited, so we opted not for an all-singing all-dancing £100,000 3D printer, but for a much more affordable £900 consumer grade printer. The kind of printer that you’d see in schools and in small hobbyist workshops.

The very first thing I printed back in early 2014 was a Hello Kitty Darth Vader head. We have since published our first paper based around technology developed with that 3D printer. We obviously learnt a lot in the intervening 3 years.

More than just a toy

While we may have started playing with 3D printing because it was an ‘interesting’ idea, within a few short months our printer stopped being a fun toy and started producing useful parts and even spawned entire projects.

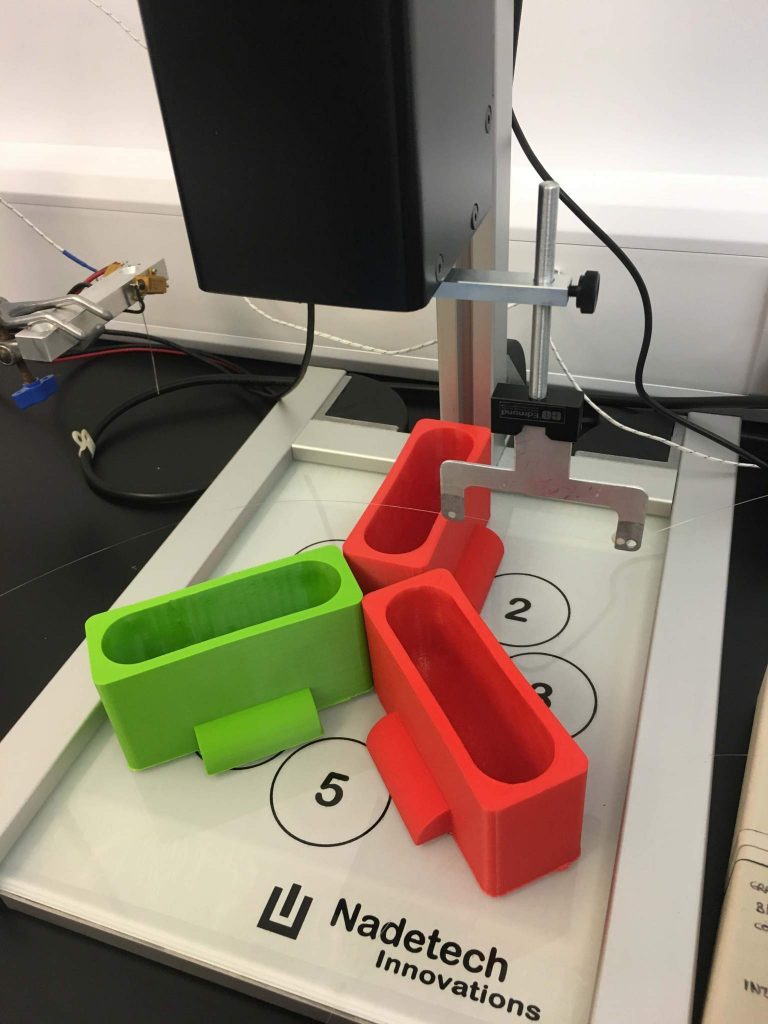

At first we were making models of things we were planning on having made professionally. Quickly designed in Sketchup and then printed out. Or more realistically: printed, thrown away, fixed and re-printed. It greatly improved our own talent for designing parts and cut down the number of expensive versions we kept having to have made.

3D printers are marketed as great prototyping tools but many come with warnings saying that they shouldn’t be used to make final parts. But while making prototypes and testing boxes or stands we started to find that they were perfectly functional. So the orders for the professionally made parts kept getting further and further delayed until eventually, we just stopped at the 3D printed part.

Then we started to get bolder and began printing things that we’d never considered making out of plastic, such as sensor holders and even some reaction housing. The parts were cheap and quick to produce, and thanks to being made of a plant based plastic, mostly guilt free.

Since then they have become a fundamental part of our research. If we have a laser setup that is very slightly out of alignment then we 3D print new mounts. If I was running an experiment which required 7 samples of material to be carefully prepared, I’d print a 7-hole tube rack with embossed labels to reduce the risk of making mistakes in the process. If a beaker needs to be 4.3 cm higher to match up to a tube, I print a 4.3 cm high stand.

The 24/7 lab technician

Having a 3D printer is like having instant access to a technician who works nights, rarely complains and likes to be well oiled about once a month. They need some setting up and an understanding of their foibles, but once they are settled in they are crazy productive at solving innumerable lab problems.

3D printers have also found a role in teaching. As any new lecturer will tell you, there is a huge drive to diversify teaching styles to try and better reach students. The examples often used are looking for ways of improving student interaction or showing them animations and videos. I now have a number of large scale physical models of fiber optics and proteins that I pass round during lectures. Being able to handle and look inside objects seems to really engage students.

Some of these models I have taken the time to design, some are models that other researchers have made available through open access 3D model repositories.

Better than even that is that all of this technology is available to anyone wanting to try it out. Pushing what is possible on 3D printers means that something we developed in our university labs could be instantly and cheaply made and used in a school. From racks to complex sensors, anyone can download and make scientific equipment and in all likelihood do things with it we never even imagined.

With all of these examples I am trying to set out the breadth of places 3D printing is just starting to help out in our labs. More and more researchers and academics are beginning to see the possibilities of 3D printing for helping in research and teaching. If nothing about 3D printing changed in the next 5 years then I’d still expect that it’s use in research labs will only grow as people recognize it’s usefulness. But with improvements in quality and reductions in cost the rise of 3D printing in the lab will be swift and research changing.

This is a guest post in our series looking at the future of 3D Printing, if you’d like to participate in this series then contact us for more information. For more insights into the 3D printing industry, sign up to our newsletter and follow our active social media channels.

Don’t forget that you can vote now in the 1st annual 3D Printing Industry Awards.

More information about 3D printing research at Cranfield University is available here.

#futureof3Dprinting

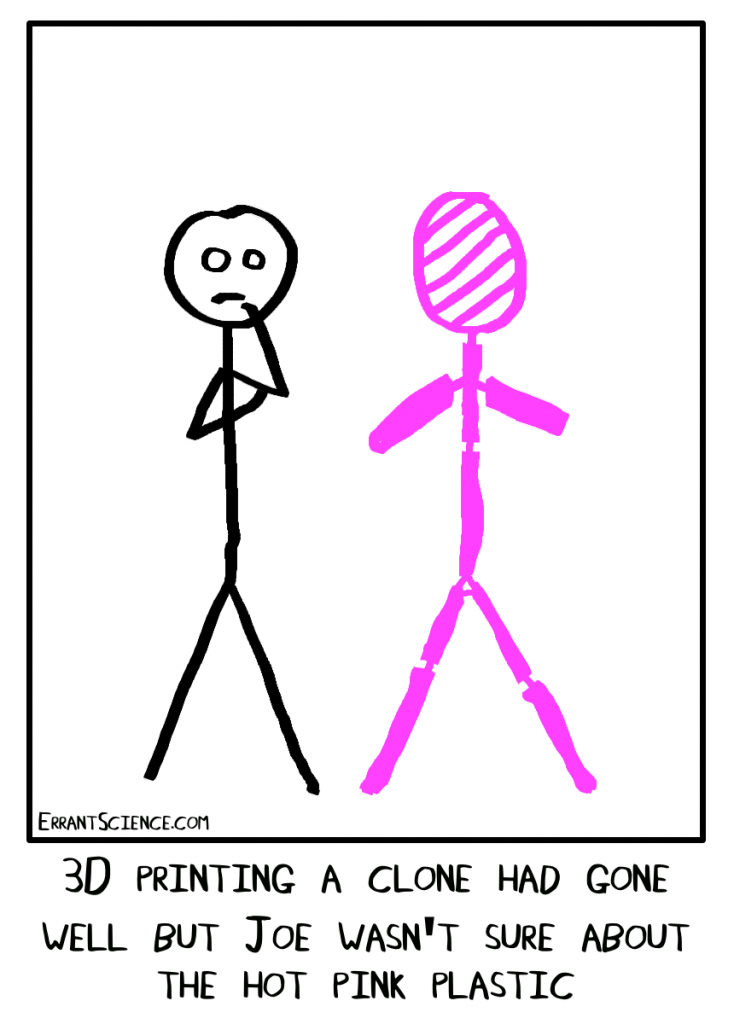

Featured image is an illustration by Dr. Matthew Partridge for his comic series Errant Science. You can also find regular updates from him on Twitter @MCeeP.