After the first industrial revolution shifted the unit of production from the home to the factory, manufacturing became an area far removed from daily life. When you buy an object in a shop, chances are it was manufactured thousands of miles away in factory. In actual fact, even if a product is made locally, it is still created based on the decisions of people we would never meet in our lifetime. Consumers, though essential to the survival of a product, are generally far removed from the production process, but with 3D printing all of that is starting to change – even when it comes to medicine.

The democratization of medication

At London’s Open Web MozFest in October 2016, I had the pleasure of hearing a seminar by Jason Bobe, associate professor at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Bobe’s specific field of interest is in the democratization of healthcare for which he asses the benefits and pitfalls of sharing medical data, and promotes the sharing of genomes.

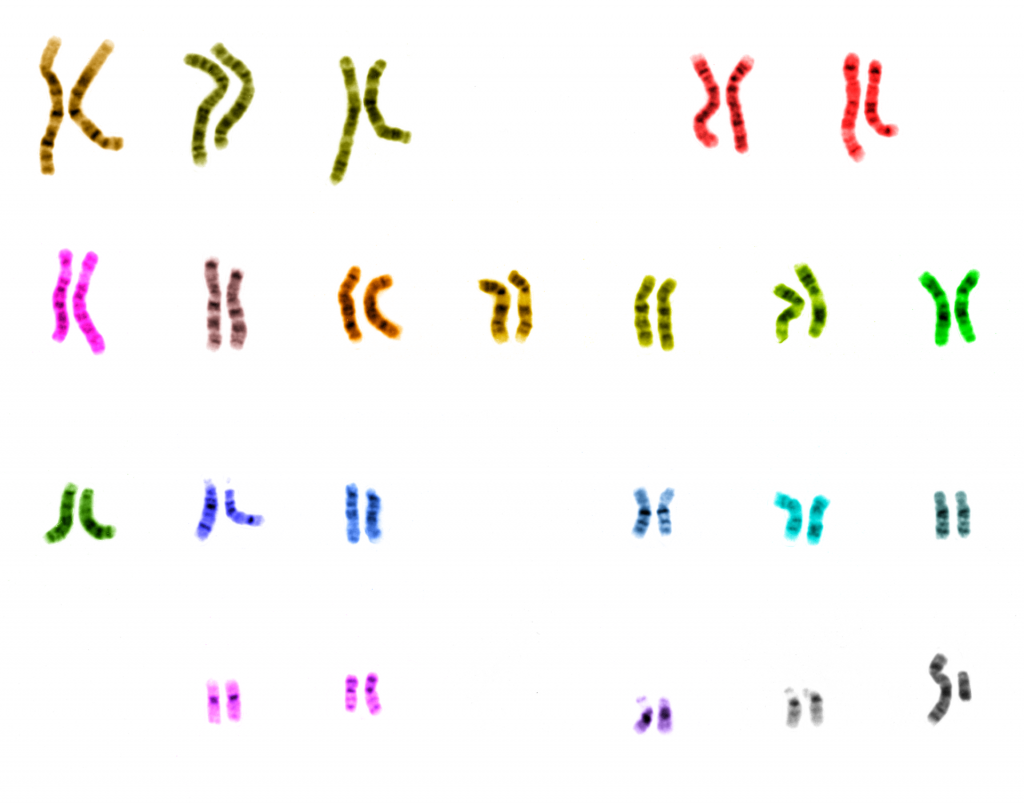

What is a genome?

A genome is our genetic makeup. It can reveal all the details of hereditary, underlying and existing medical conditions, genealogical lineage, things consumed by the body, and of course details like eye color and gender. Bobe’s case for sharing this information is to make medicine, frequently a one size fits all or blanket solution to health problems, patient-specific to better suit individual needs.

Anyone who has ever been present at a party knows full well how people’s bodies react differently to substances, i.e. those of whom don’t handle a glass of wine very well, or that person who drinks everybody else under the table, even in spite of their size (Ed – no comment!). So, the case for personalized medication is made. The same applies to surgical aids and implants – all of our bodies are different, so why are they medicated, or operated on, in the same way?

The FDA’s approach

In a video titled ‘The 3Rs of 3D Printing: FDA’s Role’ the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) explains how they are working with companies to better understand 3D printing technology, preparing for the wave of 3D printed pills, implants and (eventually) organs and tissue.

The Administration is working to internationally standardize some methods, and is continually working on its guidelines to better serve businesses and individuals using 3D printing for medical purposes.

The three Rs they discuss are Regulation, Research and Resource, which helps the FDA to cover all bases when it comes to simultaneously protecting and innovating for the public benefit.

Certified FDA materials

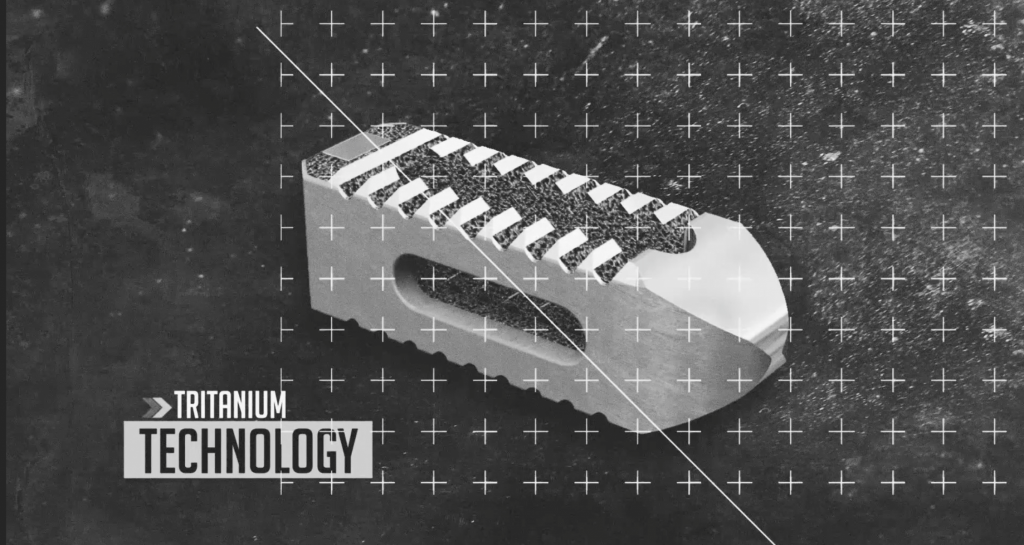

SPRITAM epilepsy medication was the first pill to have attained FDA approval in August 2015. Medical-grade PEEK plastic used to make Spinal Elements’ Firefly surgical guides also achieved FDA approval in 2016, alongside Stryker’s Tritanium metal lumbar cages, and many other 3D printing applications have now received 510(k) clearance.

Though the FDA is right that it may be years before the world has a fully-functioning 3D printed organ, the world has already seen 3D printed biological matter successfully implanted into animals. So 3D printed bio-matter, though on a small-scale, may make it into humans sooner than we think.

Featured image shows a selection of vintage apothecary medicine bottles. Photo via callmekato on Flickr.