3D printing has evolved as a means of replacing the world’s lost coral reefs. Many projects, including the efforts of SECORE International and Boston Ceramics, are putting the method into practice and seeing positive results from their introduction to the ocean.

As a relatively new approach to marine restoration, research surrounding 3D printed reefs and their potential impact on the sea bed’s flora and fauna is limited. In a recent study, Emily J. Ruhl and Danielle L. Dixson, affiliates of the University of Delaware’s School of Marine Science and Policy, investigate how the introduction of 3D printed coral affects the settling of natural coral larvae, and the reef-native damselfish.

Creating the perfect 3D printed habitat

Ruhl and Dixon’s experimentation uses 3D printed replicas of P. damicornis and A. formosa, native coral species of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Photogrammetry was used to create digital 3D models of the corals, using Autodesk ReMake to stitch the photographs together. The models were 3D printed variously on Lulzbot Taz 5, Lulzbot Taz 6, and Makerbot Replicator 2 machines to match the dimensions of their natural counterparts. Four different material filaments were selected for the study based on cost and feasibility values, like biodegradability. These were:

– A durable, Colorfabb co-polyester based filament, referred to as “nGen”

– A second Colorfabb filament of a similar composition, referred to as “XT”

– Colorfabb biodegradable PLA/PHA, dubbed simply “PLA” in the study, and,

– Biodegradable, stainless-steel reinforced Proto-Pasta PLA, termed “SS.”

Prior to use, each of the 3D printed coral models were conditioned in sea water for one week. When testing, the 3D printed samples were arranged in a tank alongside a control sample of natural fish bone coral.

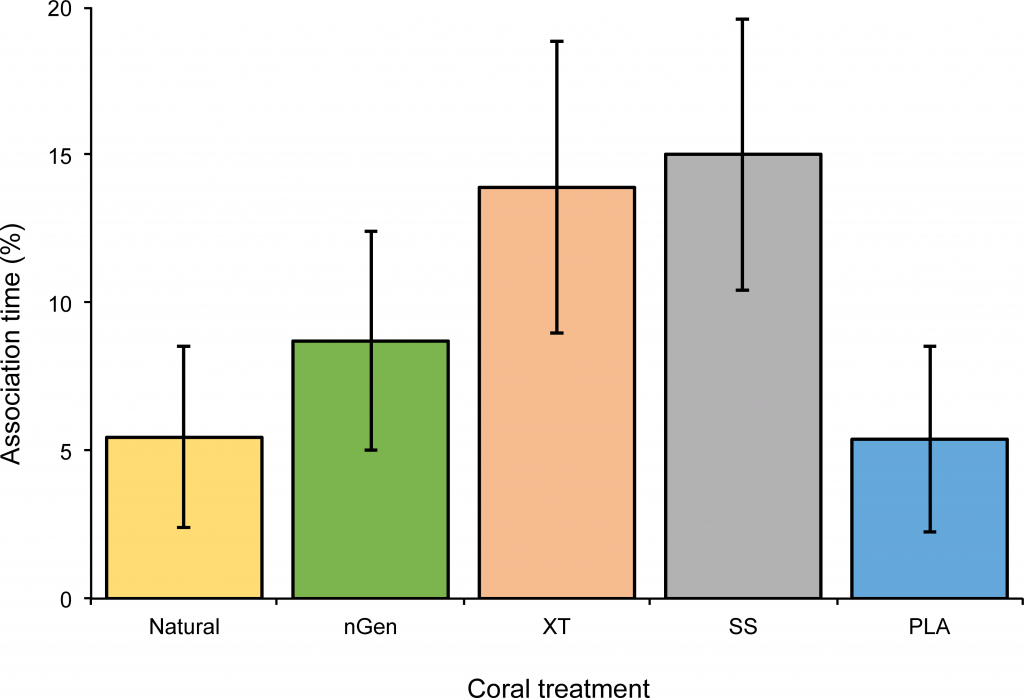

In the first study, damselfish were individually placed in tanks within see-through mesh cylinders, allowing them to habituate for 15 minutes. After habituation, the damselfish were released, and observed for a further 15 minute period. In this time, researchers looked for the fish’s association with a particular piece of coral – indicated by 5cm proximity to the coral when the fish was either stationary or slow-swimming. Association was also recorded if the fish swam away and returned to a favoured coral piece. In further observation, the team examined the damselfish’s defensive behaviour and ability to seek refuge, making sure they did not act abnormally under the conditions.

In the second set of tests P. astreoides larvae (a hardy coral species) were pipetted into different aquarium tanks. Settlement, i.e. the larvae’s attachment to one of the 3D printed coral models, was studied over the course of 14 days.

An effective means of rejuvenating coral reefs?

The results of both observations showed that neither species discriminate between the 3D printed and neutral coral. Furthermore, the damselfish did not display modified behaviours when in contact with the artificial environments.

In the case of the coral larvae in particular, “P. astreoides displayed significantly higher settlement when provided with 3D printed settlement surfaces than when provided with no settlement surface.” The larvae’s growth and mortality rates were not significantly different from the control sample either.

Though there is still a lot to understand about the rejuvenation of natural coral, these results are very positive concerning the integration of 3D printed coral. In conclusion, Rahul and Dixon state, “Our results suggest that the 3D printed models used in this study are not inherently harmful to a coral reef fish or species of brooding coral, supporting further exploration of the benefits that these objects and others produced with additive manufacturing may offer as ecological research tools.”

The full study, “3D printed objects do not impact the behavior of a coral-associated damselfish or survival of a settling stony coral” is available open-access in PLOS One journal.

For more of the latest 3D printing research sign up to the 3D Printing Industry newsletter, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.

Create a profile on 3D Printing Jobs now to advertise new academic opportunities.

Featured image shows 3D printed replicas of P. damicornis and A. formosa coral. Image via PLOS One