Technology and medicine embraced in Michigan to give a future to a child once fated to never leave the hospital. In the first ever experiment and surgery of its kind, Doctors at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital successfully implanted a tracheal splint printed as a biopolymer called polycaprolactone. Kaiba was only six weeks old when he stopped breathing at a restaurant and required emergency breathing aid. Diagnosed with tracheobronchomalacia, a flaccidity in the supporting cartilage of the trachea that causes tracheal collapse and possibly spreads to the bronchi, Kaiba faced daunting odds, but his parents held on to hope and were willing to try experimental measures.

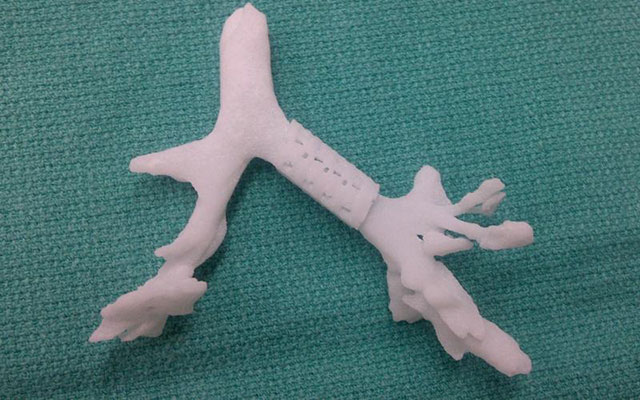

In stepped Dr. Glenn Green, associate professor of pediatic otolaryngology at the University of Michigan who collaborated with Scott Hollister, Ph.D., professor of biomedical engineering and mechanical engineering as well as associate professor of surgery at the University of Michigan. With emergency clearance from the FDA, they performed an imaging CP scan and identified the needs specific to Kaiba’s condition. Hollister used the information to create a model splint for surgery. The splint needed to be biocompatible, so they picked a biopolymer known as polycaprolactone for its plasticity and bioresorable nature. It allows anterior and posterior movement and will degrade naturally after three years. Sewn onto the bronchi, the splint provided skeletal support. Even more impressive than the 3D printing utilizing the biopolymer particle powder was the cross-disciplinary effort between Medical and Engineering schools, doctors, faculty, and researchers to give a child a chance to live with an unprecedented procedure.

The severe form of tracheobronchomalcia Kaiba carried turned him blue and left him dependent on a ventilator as he stopped breathing daily. His parents prayed every day for their baby. Immediately after his procedure, his lungs rose with breath and a mere 21 days later he was free of the ventilator. Both of his parents, overwhelmed with emotion, spoke with welling eyes: ”It means the world to me, just knowing something worked and saved my child’s life,” said Kaiba’s mother. His father, with wet eyes and a smile captures the lasting meaning of the 3D printing procedure, ”He’ll tell the story about his life: how he made it, how he’s doing, and how far he’s going to go.”

Source: UofMHealth