Researchers at the Medical University of Vienna have created a miniature 3D printed model of the human placenta, also known as an organoid, to better understand the causes of pregnancy complications.

The organoid models are miniature simplified replicas of larger organs, made through the combinations of stem cells and 3D printing. While they are not exact functioning replicas of their larger organ counterparts, the organoids recapitulate the intricate physical and biological features of an organ.

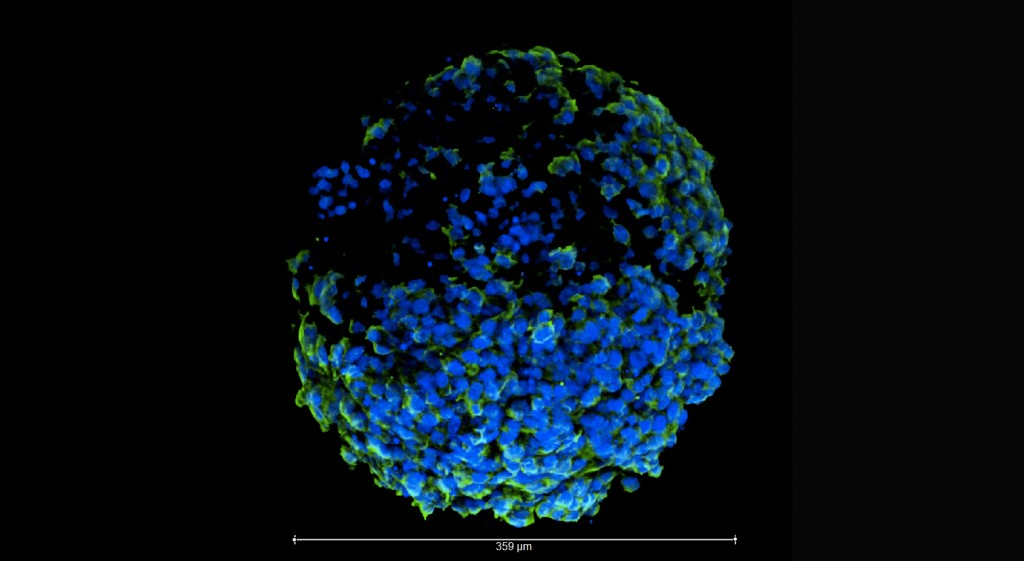

The new placenta model

In comparison to 2D cell cultures grown in petri dishes, an organoid’s cells grow in a three-dimensional environment where they more regularly communicate with each other. This allows for accurate testing. The researchers believe this model could improve our understanding of the causes of pregnancy complications.

This particular model marks the first time a self-renewing organoid of the human placenta has been made, which means the organoid’s stem cells continue to form new tissue over time.

According to the researchers, this new model could be used to study the effects of drugs on developing placenta, leading to the identification of possible harmful effects caused by treatments taken during pregnancy. However before any drug testing occurs, the researchers plan to use their new technology to study and better understand how the human placenta develops.

3D Organoids

Unlike previous placenta models, which were 2D and kept in petri dishes, this new model replicates the 3D structure of the human placenta while also containing the three main types of cells that make up the placenta.

Martin Knöfler, the lead researcher on the project, said in a recent article, “No organoid system for the human placenta was available before. In the past, preparations of primary trophoblast cells didn’t survive longer than approximately one week.”

Compared to other organs, the development of placenta organoids is not nearly as advanced.

“The fact that there were no self-renewing cell culture model systems available for the human placenta made it difficult, if not impossible, to study the causes of malfunctions. Establishment of the placenta organoid system will improve this situation significantly and will help advancing drug development and consequently medical treatments for dangerous gestational disorders,” says Knöfler.

3D printing and organ study

Several universities have also been developing 3D printed organoids, such as the University of Maryland, whose ScD group won the National Eye Institute 3D Retina Organoid challenge. The NEI awarded the group $90,000 for their proposal to 3D screen print layers of neurons in order to make something that resembles the human retina.

Additionally, Aether, with its ASAR system, an AI program for 3D printing organs replicas, has allowed for more accurate medical examinations. According to Knöfler, the Centre for Trophoblast Research at the University of Cambridge has also been developing 3D organoids of human placenta, but their research has yet to be published.

“For the moment it is important to understand how the specific trophoblast subtypes, with their different roles, develop, and how failures in that developmental program contribute to pregnancy disorders,” said Knöfler.

Want to stay up to date on 3D printing news like this? Then sign up to our 3D Printing Industry newsletter. Alternatively, you can follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.

Sign up and post on3D Printing Jobs to explore new and exciting opportunities near you.

Featured image shows a close up of human placenta cells. Photo via Boston University.