Although 3D printing technology has, in one way or another, found a way to conquer the production of many material goods, 3D printing industrial-quality composite materials is not the easiest process. These composites, made up of a combination of multiple physically or chemically different materials, are responsible for the production of a lot of goods, from concrete to golf clubs, tennis rackets to aircraft components. Now, a team of engineers from the University of Bristol have brought us one step closer to 3D printing in high-grade composite materials with a completely new 3D printing process, which utilizes a newly implemented ultrasonic wave system.

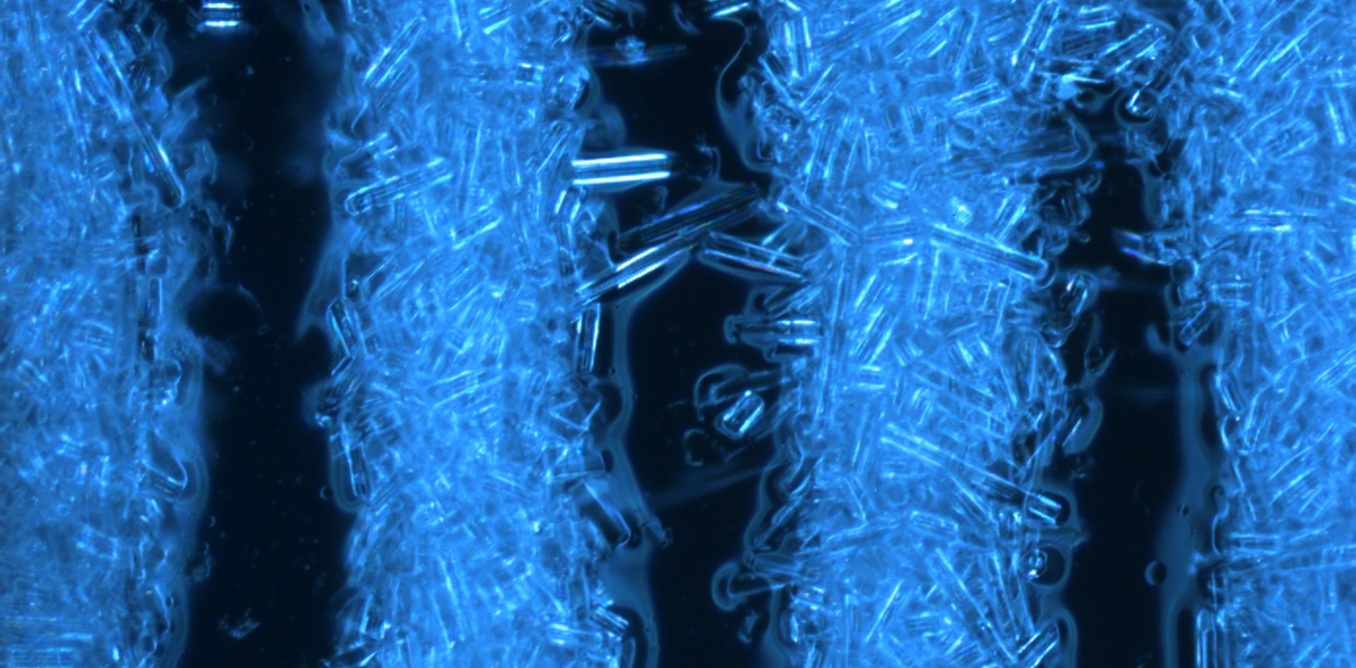

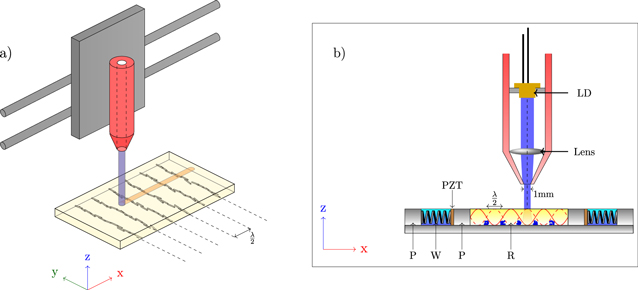

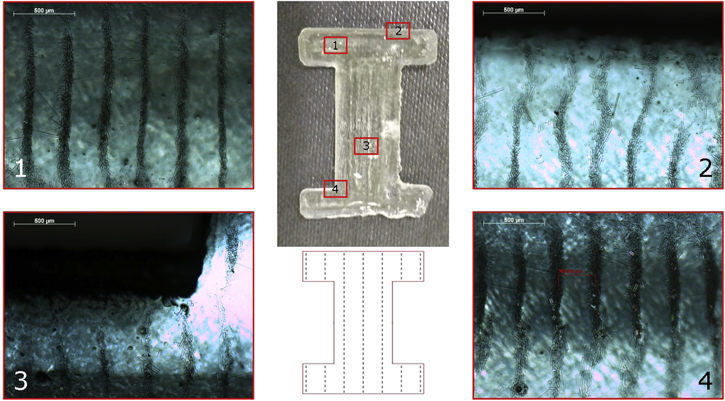

The ultrasonic wave system works by positioning millions of microscopic fibres into a reinforcement framework that strengthens the material. In order to successfully utilize the newly developed system, the University of Bristol team mounted a swappable and focused laser module upon the carriage of the three-axis 3D printing stage on their Prusa i3 RepRap. This is placed just above the ultrasonic alignment mechanism, which carefully positions the fibres as they are locally cured. By arranging these small, 3D printed fibers into a desired location, the team was essentially able to create a fiber-reinforced object.

“Our work has shown the first example of 3D printing with real-time control over the distribution of an internal microstructure and it demonstrates the potential to produce rapid prototypes with complex microstructural arrangements,” said University of Bristol’s Professor of Ultrasonics Bruce Drinkwater. “This orientation control gives us the ability to produce printed parts with tailored material properties, all without compromising the printing.”

The team claims that this ultrasonic wave system can be installed at a low-cost to almost any ‘off-the-shelf’ 3D printer, and was proven to print at a similar speed (20mm/s) in comparison to the other commonly used additive layer techniques. The University of Bristol’s team has helped to start a 3D print material revolution of some sort through their study, which will help enable 3D printers to implement ‘complex fibrous architectures’ into 3D printed objects. By utilizing these microscopic reinforcement fibres within their 3D printing process, the University of Bristol engineering team’s new method will lead to smarter, stronger, and more complex material prints.

All in all, the ultrasonic wave system will allow makers, scientists, and industrial players around the world to control the physical and chemical properties of their composite materials, which will thus lead to higher quality and more functional 3D printed products. The study detailing the ultrasonic wave system has just been published in Smart Materials and Structures by the Bristol team, including PhD student Tom Llwellyn-Jones, Professor Bruce Drinkwater, and Researcher Richard Trask.