A Spanish-Israeli team of scientists has developed a novel, 3D printed plastic-composite sensor capable of detecting small amounts of water.

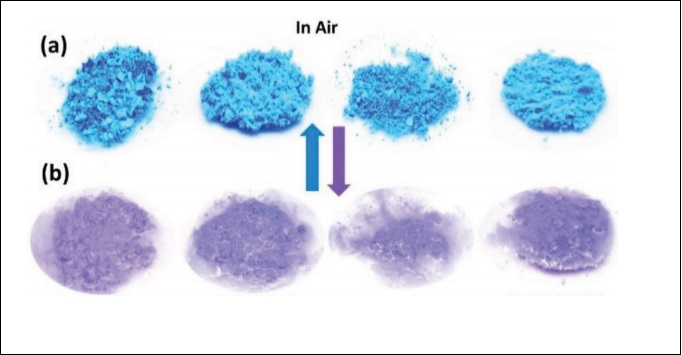

The research led by the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM) and published in Advanced Functional Materials, addresses the limitations of organic polymers in terms of mechanical and thermal properties. With the use of Coordination Polymers (CPs), i.e., multifunctional materials that are based on inorganic structures, the 3D printed water sensor can change color to detect shifts in water molecules.

“This work shows the first 3D printed composite objects created from a non-porous coordination polymer,” said Félix Zamora from the UAM and the co-author of this study.

“It opens the door to the use of this large family of compounds that are easy to synthesize and exhibit interesting magnetic, conductive and optical properties, in the field of functional 3D printing.”

New functional 3D printing materials

According to the researchers, 3D printing materials containing organic polymers, including nylon and polypropylene (PP), have their limitations. This stems from a lack of functionalities such as electrical/thermal conductivity, luminescence, magnetism, and self-healing capabilities, limiting use for various applications.

To expand the functionality of such material, the team combines the organic polymers with copper. By doing so, the team instills an ability to “sense” changes in water within the polymer, a function useful to health and food quality control, and environmental monitoring (e.g. aqua farming).

“Understanding how much water is present in a certain environment or material is important,” explained Michael Wharmby, a scientist at the DESY Research Centre in Germany, and co-author of the paper.

“For example, if there is too much water in oils they may not lubricate machines well, whilst with too much water in fuel, it may not burn properly.”

The scientists used the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY) light source, PETRA III, to analyze the changes of the material upon heating. In this case, the material was heated to 60°C, which removed the water molecule bound to the copper-based CP, ultimately causing the color change.

3D printed moisture sensing devices

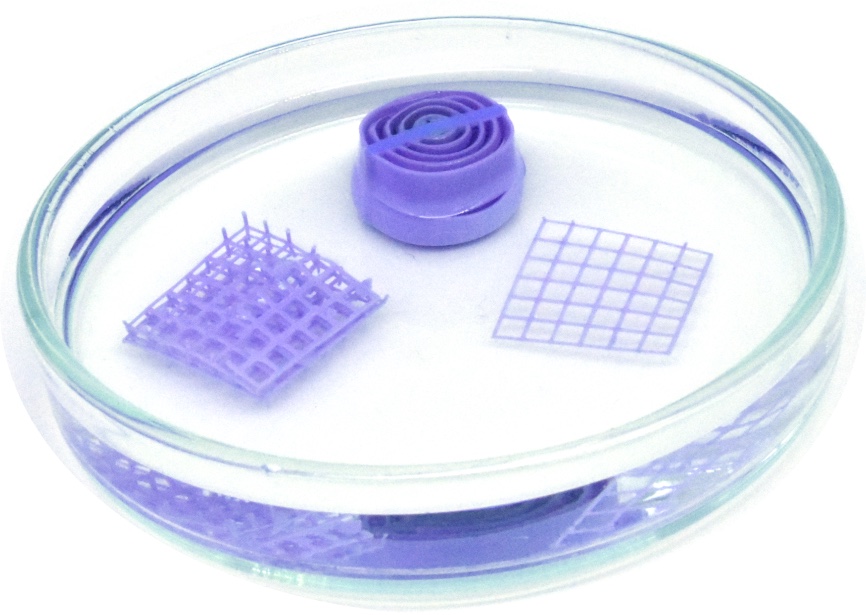

Following this, the scientists mixed the copper compound into a 3D printing ink and produce sensors of several different shapes which were also tested in water. The test demonstrated an increased sensitivity (ranging from 0.3% to 4%) to the presence of water compared to the compound by itself.

Upon this observation, Shlomo Magdassi, Professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and co-author of the study stated, “The highly versatile nature of modern 3D printing means that these devices could be used in a huge range of different places.”

“3D Printing of a Thermo‐ and Solvatochromic Composite Material Based on a Cu(II)–Thymine Coordination Polymer with Moisture Sensing Capabilities” is co-authored by Noelia Maldonado, Verónica G. Vegas, Oded Halevi, Jose Ignacio Martínez, Pooi See Lee, Shlomo Magdassi, Michael T. Wharmby, Ana E. Platero-Prats, Consuelo Moreno, Félix Zamora, and Pilar Amo-Ochoa.

For more of the latest 3D printing research, subscribe to the 3D Printing Industry Newsletter, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook.

Furthermore, for opportunities in academia, join 3D Printing Jobs.

Featured image shows variations of the 3d printable water sensor devices. When dried, in a water-free solvent, the sensor material turns purple. Image via UAM/Verónica García Vegas.