Researchers at the USA’s National Eye Institute (NEI) have developed a way of 3D bioprinting eye tissues using patient stem cells.

Using their approach, in which three different types of immature choroidal cells are printed onto a biodegradable scaffold, the scientists say it could be possible to create an unlimited supply of patient-derived tissues. These, in turn, have the potential to help doctors better understand the mechanisms behind common degenerative retinal diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

“Our collaborative efforts have resulted in very relevant retina tissue models of degenerative eye diseases,” said Marc Ferrer, Ph.D., Director of the 3D Tissue Bioprinting Laboratory at NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. “Such tissue models have many potential uses in translational applications, including therapeutics development.”

Identifying new ways of tackling AMD

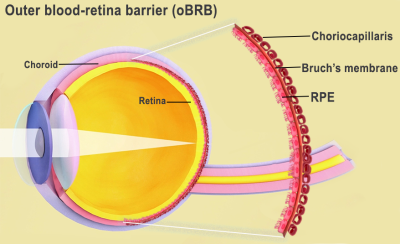

Essentially a disease that blurs patients’ central vision, AMD is caused by various factors, including age, genetics, blood pressure, and dietary issues. These triggers are understood to cause lipoprotein deposits called drusen to form outside Bruch’s membrane, an extracellular matrix (ECM) located between the retina and the choroidal capillaries of the eye.

This phenomenon not only prevents the membrane from regulating nutrients and waste around the eye, but over time, causes the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in its outer blood-retina barrier to break down, leading to vision loss. However, while the triggers of AMD are well-known, the way it advances remains something of a mystery.

“We know that AMD starts in the outer blood-retina barrier,” explained Kapil Bharti, Ph.D., who heads the NEI Section on Ocular and Stem Cell Translational Research. “However, mechanisms of AMD initiation and progression to advanced dry and wet stages remain poorly understood due to the lack of physiologically relevant human models.”

The NEI’s 3D bioprinting initiative

In an effort to facilitate further research into AMD progression, Bharti and his team have come up with a way of 3D bioprinting tissues from patient stem cells. In this technique, pericytes and endothelial cells, key components of capillaries and fibroblasts, which give tissues structure, are combined into a novel hydrogel. This gel is then printed onto a scaffold which is capable of supporting cell growth.

Within days of creating prototype biodegradable scaffolds, the scientists found that implanted cells had begun to mature into a dense capillary network. On day nine, the researchers decided to seed retinal pigment epithelial cells on the flip side of the scaffold, and by day 42, they found that tissues had reached “full maturity.”

Subsequent tissue analyses and genetic and functional testing showed that the resulting tissues looked and behaved similarly to a native outer blood-retina barrier. Under induced stress, they even exhibited patterns of drusen deposits underneath the RPE and progression to late dry-stage AMD, whereas the administration of Anti-VEGF drugs suppressed vessel overgrowth and restored tissue morphology.

Having proven the efficacy of their approach, Bharti and co. are now using their bioprinted blood-retina barrier models to continue studying AMD. Moving forwards, the team plan to experiment with adding other cell types to their process, such as immune cells, with the aim of creating more lifelike tissues that enable them to make further discoveries.

“By printing cells, we’re facilitating the exchange of cellular cues that are necessary for normal outer blood-retina barrier anatomy,” added Bharti. “For example, the presence of RPE cells induces gene expression changes in fibroblasts that contribute to the formation of Bruch’s membrane – something that was suggested many years ago but wasn’t proven until our model.”

3D printing’s eye treatment potential

While the 3D bioprinting of eye tissues remains at an experimental stage, conventional 3D printing has been deployed in the production of various other optical medical procedures. In 2021, surgeons at the Israeli Galilee Medical Center (GMC) developed a means of treating eye socket fractures with 3D printing and augmented reality (AR) glasses.

Later that year, a team at the University of Basel also unveiled porous 3D printed implants for treating eye socket fractures. Created using a Prusa i3 3D printer and PEEK filament, the team’s grafts were said to be capable of overcoming the bioinertness of their material thanks to their porous features, which could be tailored to enhance cellular repair.

Elsewhere, in a case where a patient’s eye couldn’t be saved, doctors at Moorfields Eye Hospital 3D printed a prosthetic eye for a London man in need. Using the technology, the team were able to create an artificial eye with a more realistic look than a traditional acrylic prosthetic that could be manufactured in a much shorter time frame.

The researchers’ findings are detailed in their paper titled “Bioprinted 3D outer retina barrier uncovers RPE-dependent choroidal phenotype in advanced macular degeneration.”

The study was co-authored by Min Jae Song, Russ Quinn, Eric Nguyen, Christopher Hampton, Ruchi Sharma, Tea Soon Park, Céline Koster, Ty Voss, Carlos Tristan, Claire Weber, Anju Singh, Roba Dejene, Devika Bose, Yu-Chi Chen, Paige Derr, Kristy Derr, Sam Michael, Francesca Barone, Guibin Chen, Manfred Boehm, Arvydas Maminishkis, Ilyas Singec, Marc Ferrer and Kapil Bharti.

To stay up to date with the latest 3D printing news, don’t forget to subscribe to the 3D Printing Industry newsletter or follow us on Twitter or liking our page on Facebook.

While you’re here, why not subscribe to our Youtube channel? featuring discussion, debriefs, video shorts and webinar replays.

Are you looking for a job in the additive manufacturing industry? Visit 3D Printing Jobs for a selection of roles in the industry.

Featured image shows a diagram of the inside of the human eye. Image via the National Eye Institute.