The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) is embracing 3D printing, and North Manchester General Hospital (NMGH) has joined the charge towards innovation with its newly established 3D printing lab.

The lab was established by reconstructive scientist Oliver Burley who made a business case and fundraised for an in-house 3D printing lab, before equipping it with 3D software and a PolyJet 3D printer.

The lab is now powered by three full-time members who work with the nine oral-maxillofacial consultants at the Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust (PAHT), taking on weekly tasks.

Advantages of an in-house 3D printing lab

After completing his MSc in reconstructive science, which involved the application of 3D printing, Burley assumed a management position at NMGH. Here, he made a business case for an in-house 3D printing lab, holding a consultation to get consultants on board.

The first argument to be made in favor of bringing 3D printing into the hospital itself was cost savings. NMGH was spending hospital was spending £120,000 ($166,000) annually on outsourced 3D printing projects.

With an expected 20 cancer cases per year and 8-10 trauma-related expected per year, a cost-benefit analysis suggested that bringing 3D printing in-house would be more economical.

The second argument made was the reduction of the time the surgeon spends under anesthetic in the theater. This could be reduced by using 3D printed models or cutting guides in surgery planning.

The final argument made was a cut in delivery time. With contractor communications taking up valuable time, having an accessible lab on-site would improve the workflow of procedures. While the lab does spend a significant amount on licenses, these remain the same all year regardless of the number of cases.

The use of 3D printing in the lab

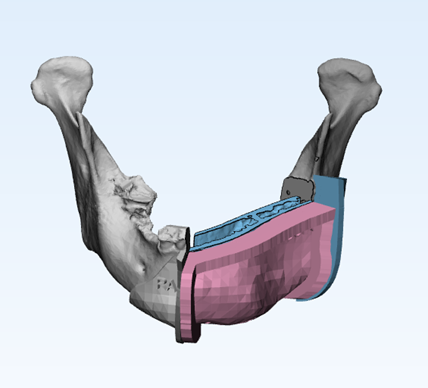

After a donor part-funded the lab, Materialise Mimics Innovation Suite was chosen as the modeling software because of its DICOM segmentation, while ProPlan CMF was chosen for surgical planning, reconstructions, and jaw osteotomies. “We’re using 3D in virtually every case now,” Burley said, adding:

“I envisage that in five years’ time if you want to be a fully-fledged cancer center within an NHS Trust, one of the requirements will be to have a 3D printing facility. I feel that’s the way it’s going.”

The lab’s main cases are head and neck cancer patients who require reconstruction, including the use of DCIA bone grafts to reconstruct the upper or lower jaw of cancer patients. With new resources provided the lab is taking on smaller cases, and it may even be used in the orthopedics, neurology or rheology departments.

3D Printing and the NHS

The NHS in Wales has achieved significant advances in 3D printing, including a world first combined bone graft and 3D printed implant surgery, and a life-saving 3D printed rib implant.

There are also signs that that 3D printing will expand further across the NHS. In February, a new $30 million research center for the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the R&D wing of the NHS, opened in the south-western city of Bristol.

The Bristol Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) is to include facilities for tissue engineering through bioprinting, and it will build upon existing cardiovascular research in Bristol that has previously 3D printed hearts.

Is this an inspiring use of 3D printing? Today is the final day to put forward nominations for the 3D Printing Industry Awards 2018. Submit yours now.

Want to design this year’s trophy? Protolabs is sponsoring the 2018 3D Printing Industry Awards design competition. Submit your design now to win a 3D printer.

For more stories on 3D printing in medicine, subscribe to our free 3D Printing Industry newsletter, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.

Featured image shows a medical model 3D printed on NMGH’s PolyJet 3D printer. Photo via Oliver Burley.