This is a thought leadership article in our series looking at the future of 3D printing.

Len Pannett is an operational strategy consultant at Visagio Ltd, where he helps organisations to realize their operational aspirations. He is a specialist in the impact of 3D printing on supply chains, and is a founder of Supercharg3d.com.

The future of 3D printing for the supply chain by Len Pannett

Every day brings with it news of innovative ways that 3D printing is being used, the amazing things that it can make, and how it will transform our world beyond all recognition. There is talk that it will radically change supply chains, from eliminating the need to store spare parts and having 3D printers in car service centres, to more fantastic claims of solving sustainability issues.

Despite 3D printer sales growing at around 25% per annum, hinting that it is having a significant impact in how things are made, 3D printing is not yet generally used in manufacture. It remains an interesting tool for making things, intriguing and enigmatic for many businesses, wondering how best to meet their customers’ needs.

Of course, 3D printing is ideal in situations where there is a requirement for making things with complex designs, or which require mass customization or fast design-to-delivery cycle time, all for a lower cost.

So will 3D printing become all-pervading over the next five years? Unlikely. However, it will enter mainstream operational planning and begin to shape longer-term supply chain models.

3D printing increasingly considered

Five years is not a long time in business’s strategic planning. Most companies have a five-year planning cycle in which they consider how their customers’ demands will change and how best to meet those.

They will take into account what tools are available and how best to arrange their operations. In many cases, that analysis will include identifying and trialling new technologies, and 3D printing is increasingly entering into those considerations.

Sure, 3D printing has considerable advantages in design flexibility, particularly in the production of complex forms, as well as in reducing the end-to-end time to make things.

It has a transformational flexibility to cope with “lots of one”, batches of single items, something which is costly and time consuming to do otherwise. However, it remains an immature set of technologies with many constraints, direct and indirect.

Not yet a manufacturing panacea

Despite being over 30 years old, 3D printing is not yet a manufacturing panacea. It requires a new approach to design, one that is less constrained than traditional reductive manufacture and which appreciates the nuances of 3D printer capabilities.

The materials that 3D printers use need to be specially prepared and matched to the 3D printing technology being used. During manufacture and immediately afterwards, 3D printed items need to be tested and, if they are good enough, treated in post-production and finished. Those stages all add to cycle times and cost, and have to be planned for.

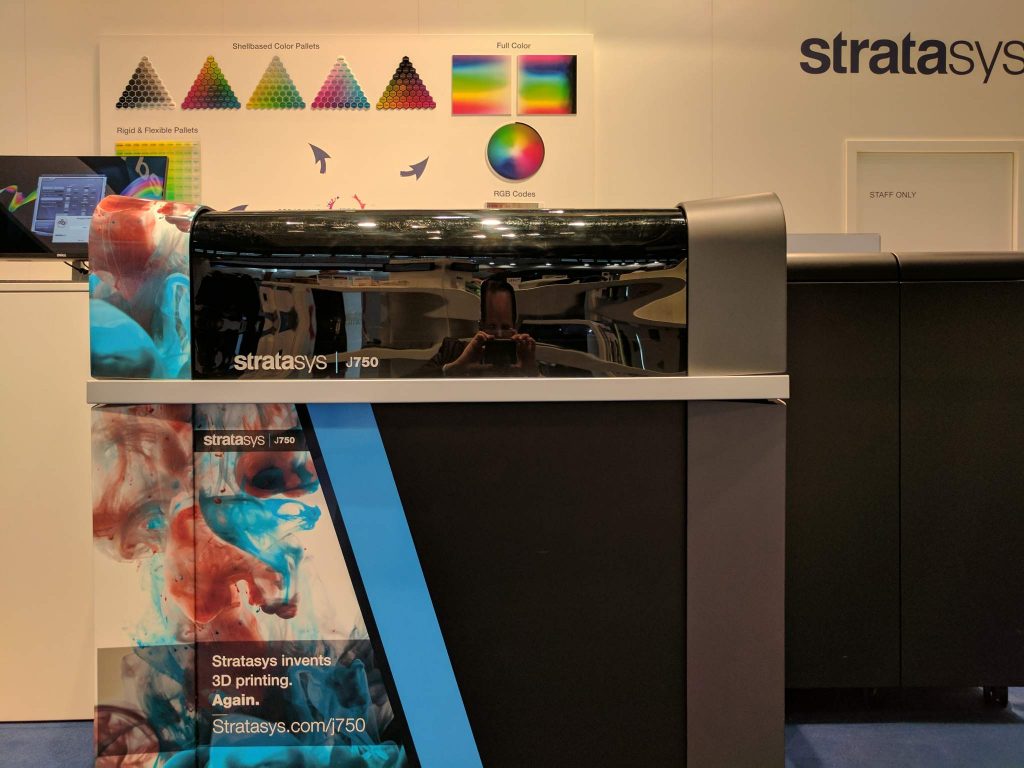

The most contemporary 3D printers, such as Stratasys’ J750, can make items with several colours at the same time, although true multi-material printing – a key requisite of most manufactured items – is still several years away.

While innovative designs have succeeded in simplifying assembly, for instance, by internalising hydraulics in some items, laying internal conductive pathways, such as wires or metal tracks, with the qualities necessary of production “things” will not be possible for a while yet.

Moreover, the question of sustainability may hold back those sorts of advances – consider the difficulty of recycling a multi-material tyre or a Tetrapak carton with it paper, metal and wax layers.

This means that, in the short term, 3D printers will continue to be used for making single material items, even if designs will be increasingly complex and made with fewer individual parts. Assembly will still be needed, bringing together parts of different materials.

How to adapt for 3D printing?

That doesn’t mean that the situation is static for 3D printing – as awareness of it and what it can do increase, so it will enter into operational considerations at board levels. According to a recent survey by consultancy Strategy&, 45% of companies surveyed are not currently considering 3D printing for their product lifecycles, and 95% of those respondents expect it to be included in five years’ time.

Tangible changes in how it is used and the actual impact is has on supply chains will change little, however. So how will those boards adapt?

As with any new technology, the decision to use 3D printing must start with identifying how it can help to achieve the business’s goals.

This means looking at how its customers’ needs can be met, considering if 3D printing can do so better than traditional methods and what else the business could do with 3D printing that wasn’t viable before.

This begins with manufacturers understanding their products’ bills of materials and assessing whether there is an advantage in 3D printing each component. GE and Airbus have found that the technology allows them to redesign aircraft parts to reduce their weight, saving costly fuel. Additionally, there may be operational advantages, such as reductions in inventory costs, faster end-to-end cycle times, and higher levels of perfect orders.

For instance, that analysis has led to Boeing deciding to use 3D printing to make future satellites, as reported on 3Dprintingindustry in February. If there is a case – or even just to see what it can do – then the business must consider how 3D printing will realise it.

Making the business case for 3D printing

Questions will include: which 3D printer is needed, with what materials? Should it buy that 3D printer or use a printing service? Should 3D printing replace or enhance existing manufacturing? Where should the 3D printers be placed?

It needs to consider the wider change factors to use it properly: does it have the skills in-house to design things for it; how are its designs protected by IP; how does it assure the quality of its 3D printed parts; how does it price them, and so on. Ford, Mercedes-Benz and BMW are all looking at how to improve serviceability of their cars with 3D printing-based innovation, such moving spare parts production closer to servicing centres and allowing those centres to make those spare parts on demand. This model is also being considered by mining companies, such as Rio Tinto, and their suppliers, like Caterpillar.

The next five years are unlikely to see a significant change in how 3D printers are used, or in the operating models and supply chains that use them.

However, there will be a shift in mindset in businesses, which will increasingly consider 3D printing as a workable solution and develop plans for its use. Catalysed by the advent of digital manufacturing and Industry 4.0, that will result in new operational models that make use of 3D printing’s transformative capabilities and that will reach well beyond the next five years.

You can find out more here about Supercharg3d.com.

If you want to give us your perspective on the future of 3D printing then email us now.

For more 3D printing insights and analysis, subscribe to our free newsletter and follow our active social media accounts.

Read more about the future of 3D printing in the 3D Printing Industry thought leadership series.