On average, 90% of new drugs developed by pharmaceutical companies in the U.S. fail to make it to a commercial market due to inadequacy of the current screening process.

As a result, the manufacturers and researchers involved are seeking a better alternative to up the odds of the industry’s roulette, and save money in a market with an estimated worth of over $300 billion.

In recent years, 3D bioprinted organ-on-a-chip devices have been propagating as a promising solution. Containing live human cells, arranged as they would be in the body, the organ-on-a-chip devices are a closer match to our physiology than any lab rat or primate, and avoid the implications of cruelty in the process.

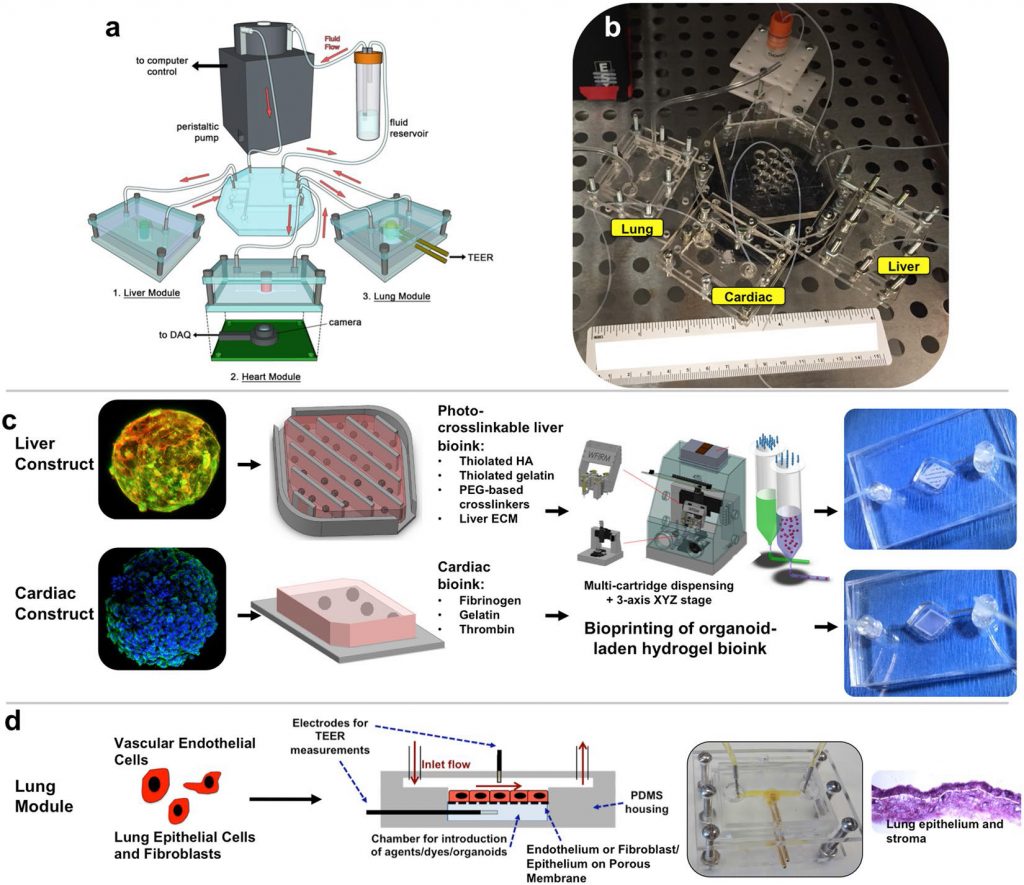

As such, the U.S. federal government has granted $24 million to a research consortium seeking to make an organ-on-a-chip model of the entire body. Led by researchers at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine (WFIRM), North Carolina, the latest paper concerning the Body on a Chip project reports the success of a system connecting three of the body’s vital organs: the liver, the heart and the lungs.

Base model of WFIRM’s 3D bioprinted heart cells beating. Clip via Supplementary Materials, Scientific Reports.

The model body

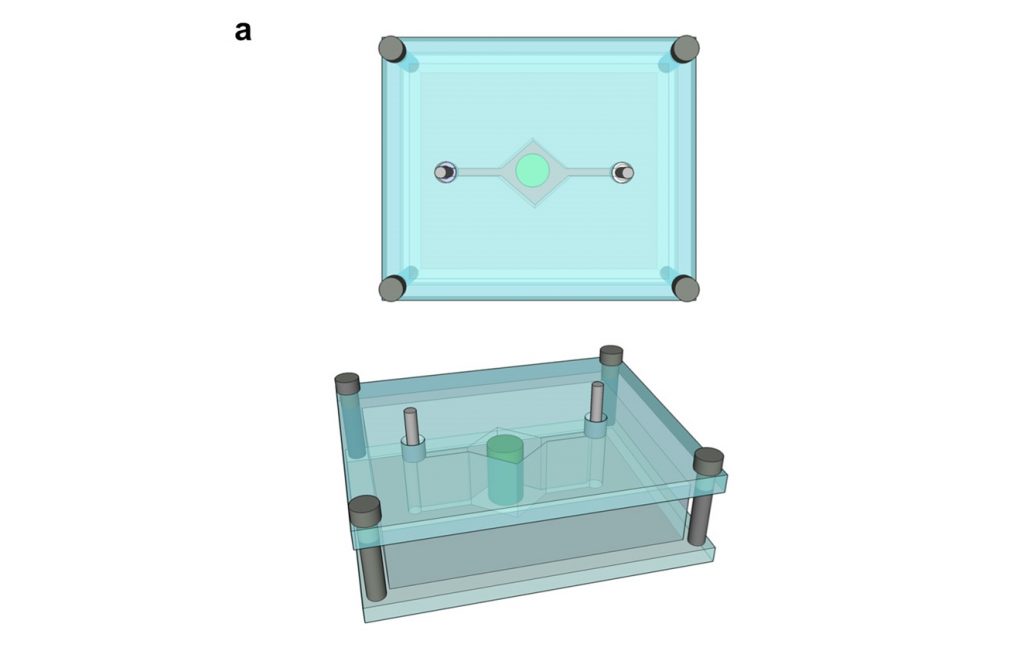

Each organ-containing chip in the WFIRM study starts out suspended in a custom-made hydrogel ink made specially for the type of cell. Using a proprietary 3D bioprinter, the cell-laden inks are written onto substrates including vessel features. The vessels are then connected by microfluidic channels, mimicking the effect of blood-flow.

Saving lives and saving money

By connecting three models of the body’s organs using blood vessel-like tubes, the Body on a Chip project has already identified some unexpected side effects caused by common cancer drugs.

In the multi-organ system bleomycin, commonly used to treat lymphoma, cervical, testicular and other cancers, not only caused scarring to the lung but it also created problems with the heart – an effect not experienced when testing the drug in the heart model alone.

WFIRM Professor Aleks Skardal comments, “This was completely unexpected, but it’s the type of side effect that can be discovered with this system in the drug development pipeline,”

“If you screen a drug in livers only, for example, you’re never going to see a potential side effect to other organs. By using a multi-tissue organ-on-a-chip system, you can hopefully identify toxic side effects early in the drug development process, which could save lives as well as millions of dollars.”

Three down, nine to go

In the discussion, authors state that “Despite yielding countless medical discoveries, 2D cultures fail to recapitulate the 3D microenvironment of in vivo tissues. 3D systems composed of organoids or biofabricated tissue constructs have an increased capacity to respond accurately to drugs and toxins.”

It was also shown that each 3D bioprinted model considered in the study performed better than its two-dimensional counterpart. According to WFIRM director, Dr. Anthony Atala, “Eventually we expect to demonstrate the utility of a body-on-a-chip system containing many of the key functional organs in the human body,” meaning the team still have nine more organs to go.

WFIRM’s research is conducted in collaboration with teams in Boston at Brigham and Women’s Hospital; the University of Michigan; and in Maryland at the U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center, Morgan State University and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The most recent findings, as discussed in this article, can be read online in the journal Scientific Reports.

For more of the latest 3D bioprinting research, sign up to our free newsletter, follow us on Twitter and like us on Facebook.

Featured image shows the WFIRM 3D bioprinted Body on a Chip system containing heart, lung and liver cells. Photo via WFIRM