3D printing is making space more accessible, but can it help “protect our planet from both outer space threats and from those who seek to disturb the peace on Earth?”

Igor Ashurbeyli, writing in ROOM – The Space Journal where he is also Editor-in-Chief, believes that the junk left behind from 50-plus years of space exploration poses a serious threat.

Man-made space objects (MSOs), such as satellites, differ from natural space objects, like meteors in a number of ways. Primarily, the time they spend in close proximity to Earth. Meteors travel great distances across the galaxy and occasionally enter the Earth’s atmosphere, only to rapidly exit once again or break up into smaller pieces. Lacking such velocity, or kinetic energy, MSOs can remain in orbit for decades.

The threat to Earth

According to Ashurbeyli and other experts “we are locked into a truly terrifying phase of space pollution.” As dead satellites accumulate in a low Earth orbit (LEO) the likelihood of a cascading wave of fast moving junk increases. This is a situation known as the Kessler syndrome to rocket scientists, and to the rest of us from the opening sequence of the movie Gravity.

Lorenzo Ferrario is the Chief Technology Officer with D-Orbit, an Italian company working on a solution to the growing problem of space debris. “At the moment we have more or less 1,500 active satellites in orbit. But we have more than 16,000 dead satellites,” Ferrario tells me.

Imagine driving your car on a highway, and the car stops working because it breaks down or you run out of fuel. So you don’t take the car away, you just leave it there and go buy a new one. This is exactly the effect.

Space has no drag so if you launch a satellite and it stops working basically it stays there, and we have been doing this for 50 years now.

The accumulation of space debris is now reaching a point where LEO may become unusable for scientific, commercial or other missions. This means that the communication networks and other systems we depend on are under threat. Ashurbeyli warns of an even more dangerous scenario.

“It is not hard to envisage how space debris ‘situations’ could become a pretext for wide-scale military operations” writes Ashurbeyli. With geo-political tensions running high, the loss of a critical satellite might be blamed upon a rival nation by a country looking for a pretext for military aggression believes the Editor-in-Chief.

3D printing a solution

“There are two ways of approaching the space debris problem,” explains Ferrario. “Active debris removal” is “where you go up and grab some debris and take it down.” A paper published by Commercial Space Technologies Ltd. (CST), a consultancy company active in the UK and Russia, entitled Approaches to the Space Debris Problem in Russia details several of these techniques.

CST’s research demonstrates historical methods and ideas for the future. Past ideas include a proposal to use a modified Russian satellite-interceptor, the Istrebitel Sputnikov, to clamp onto fragments of space debris. Future plans might involve a belt of tungsten particles that attach to debris, increasing its mass until the MSO descends.

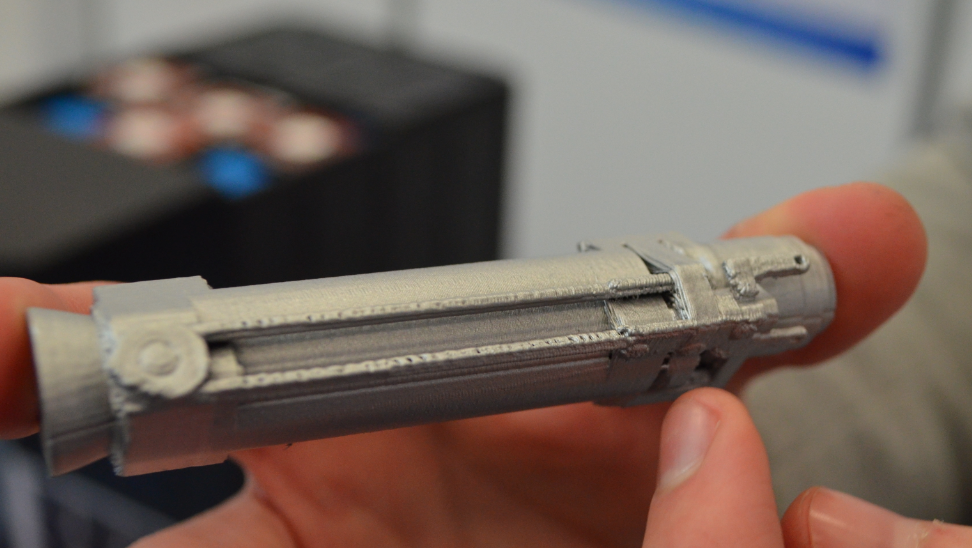

Ferrario’s company take a different approach as it makes “no sense to start cleaning if you don’t stop polluting.” He points to a shoebox sized metal object on the table in front of us and explains.

That is a decommissioning device. So it is a satellite subsystem that you load on a satellite before the launch. It’s based on solid rocket motor technology, so it’s really safe and highly reliable and the purpose of it is that at the end of life of the satellite you ignite the motor and this motor is able to bring your satellite back into the earth’s atmosphere. This helps prevent the further continuation of the space debris problem.

The prototype we are looking at is made from aluminum, and built using 3D printing. “We used AM for rapid prototyping of the ignition system, that is this box on the top,” explains Ferrario.

The advantages of 3D printing

D-Orbit choose 3D printing to make their decommissioning device because of the advantages in weight the technology offers: launching anything into orbit is an expensive business. “For a cube-sat one kilo of mass is more of less sixty to seventy thousand Euro ($68,000 to $78,000 USD) per kilo,” explains Ferrario.

3D printing also enabled an improvement in the mechanical engineering of the device. Inside D-Orbit’s prototype there “is some circuitry that commands two motors.” The motors move a slider and “this slider blocks a channel that connects the actual igniter of the motor that ignites with a spark. So this slider prevents any inadvertent ignition.”

Using 3D printing D-Orbit “moved towards something more similar to the trigger of a gun for the mechanism. That mechanism was really small and had a strange shape and could only be manufactured thanks to AM technology.”

However, for now the improvements released by 3D printing and the engineers at D-Orbit will remain theoretical.

The flight model will unfortunately not yet be additively manufactured because unfortunately metal additive manufacturing is not yet a certified European Space Agency (ESA) process, so we have to stick with the standards. However we want to go on and go through with this technology because we found that this same system could be released with additive manufacturing and the small performance, but with approximately a third of the mass.

Ferrario says, “with respect to environmental protection space debris is more or less like how environmental protection was 30 years ago.” The Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) provides guidelines for space debris regulation and most of the space agencies (NASA, ESA, JAXA etc.) around the world participate.

However, there is no organization with the powers to fully sanction space polluters. Ferrario explains the rules say, “you have to remove [the satellite] at the end of its life, but there are no fees if you don’t do that.”

Read more about 3D printing and space here and subscribe to our newsletter to receive articles like this in your inbox.

Featured image shows one impact of the Kessler Syndrome in Alfonso Cuarón’s 2013 film, Gravity.