A Virginia Tech team led by assistant professor Blake Johnson has taken a step forward in improving 3D printed personalized prosthesis. Published in Plos One, their new research details an ability to integrate electronic sensors at the intersection between an artificial limb and the wearer’s tissue – creating an unparalleled form-fitting prosthesis.

The introduction of these low-cost electronic sensors enables the gathering of data relating to performance and comfort, for example how much pressure it places on the wearer’s tissue. This information can help improve future iterations of the device. Speaking of the team’s future visions Uxin Tong, a Virgina Tech engineering graduate student and first author of the published study, comments:

“Hopefully, every parent could follow the description from the paper we published and develop a low-cost personalized prosthetic hand for his or her child.”

3D printing personalized prosthesis

The Virginia Tech project all started as an effort to help a local teen, Josie Fraticelli, who born with amniotic band syndrome, causing a lack of formation beyond the knuckles.

Johnson used his expertise in additive manufacturing and a team of undergraduate researchers to 3D print a bionic hand for Fraticelli. They then continued to improve the prosthesis using new additive manufacturing techniques, opening up a new level of customization.

According to Johnson, “Personalizing and modifying the properties and functionalities of wearable system interfaces using 3D scanning and 3D printing opens the door to the design and manufacture of new technologies for human assistance and health care as well as examining fundamental questions associated with the function and comfort of wearable systems.”

Conformal 3D printing

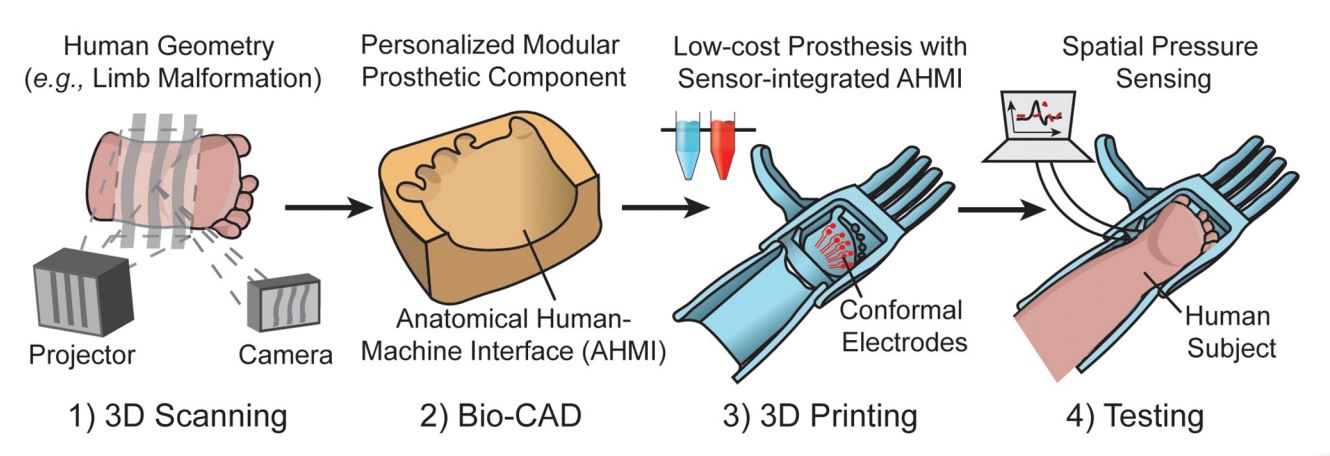

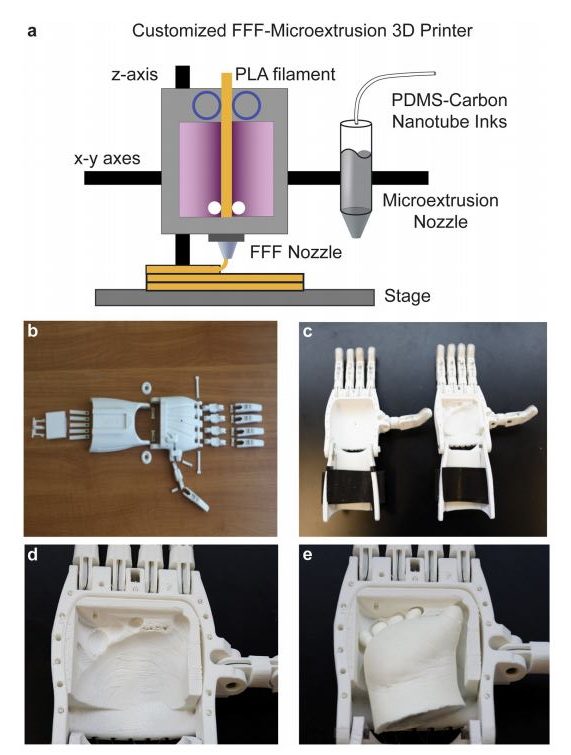

To create Fraticelli’s prosthesis the team began by scanning a mold of the teenagers hand. The majority of the prosthesis was then 3D printed, to exactly fit the mold of her hand. Then, in a further step the team call “conformal 3D printing” the team added electrodes, using a second nozzle containing a carbon nanotube-based polymer ink.

After 3D printing, the team then tweaked the prototype device to create a better fit to the teen’s palm. The end result of was an extremely form-fitting prosthesis that increased the contact between the teen’s tissue and the prosthesis by 408%, as compared to non-personalized devices. The expanded contact area helped researchers locate the areas where they should integrate sensing electrode arrays to measure pressure distribution, which helped them to further improve the design.

The future of custom 3D printed prosthesis

Making an important affirmation about the future of 3D printed prosthesis, the Virginia Tech researchers state, “Interfacing anatomically conformal electronic components, such as sensors, with biology is central to the creation of next-generation wearable systems for health care and human augmentation applications.”

“Low-cost sensor-integrated 3D-printed personalized prosthetic hands for children with amniotic band syndrome: A case study in sensing pressure distribution on an anatomical human-machine interface (AHMI) using 3D-printed conformal electrode arrays” is published online in Plos One journal. It is co-authored by Yuxin Tong, Ezgi Kucukdeger, Justin Halper, Ellen Cesewski, Elena Karakozoff, Alexander P. Haring, David McIlvain, Manjot Singh, Nikita Khandelwal, Alex Meholic, Sahil Laheri, Akshay Sharma and Blake N. Johnson.

Other recent 3D printing research from Virginia Tech scientist include the development of 3D printable piezoelectric materials, and a patent granted to a 3D printing vending machine technology for continuous manufacturing.

Submit your trophy design and cast your vote to decide this year’s winners of the 2019 3D Printing Industry Awards now.

For the latest additive manufacturing news, subscribe to our 3D printing newsletterand follow us Facebook and Twitter. Visit our 3D Printing Jobs board to find out more about opportunities in additive manufacturing.

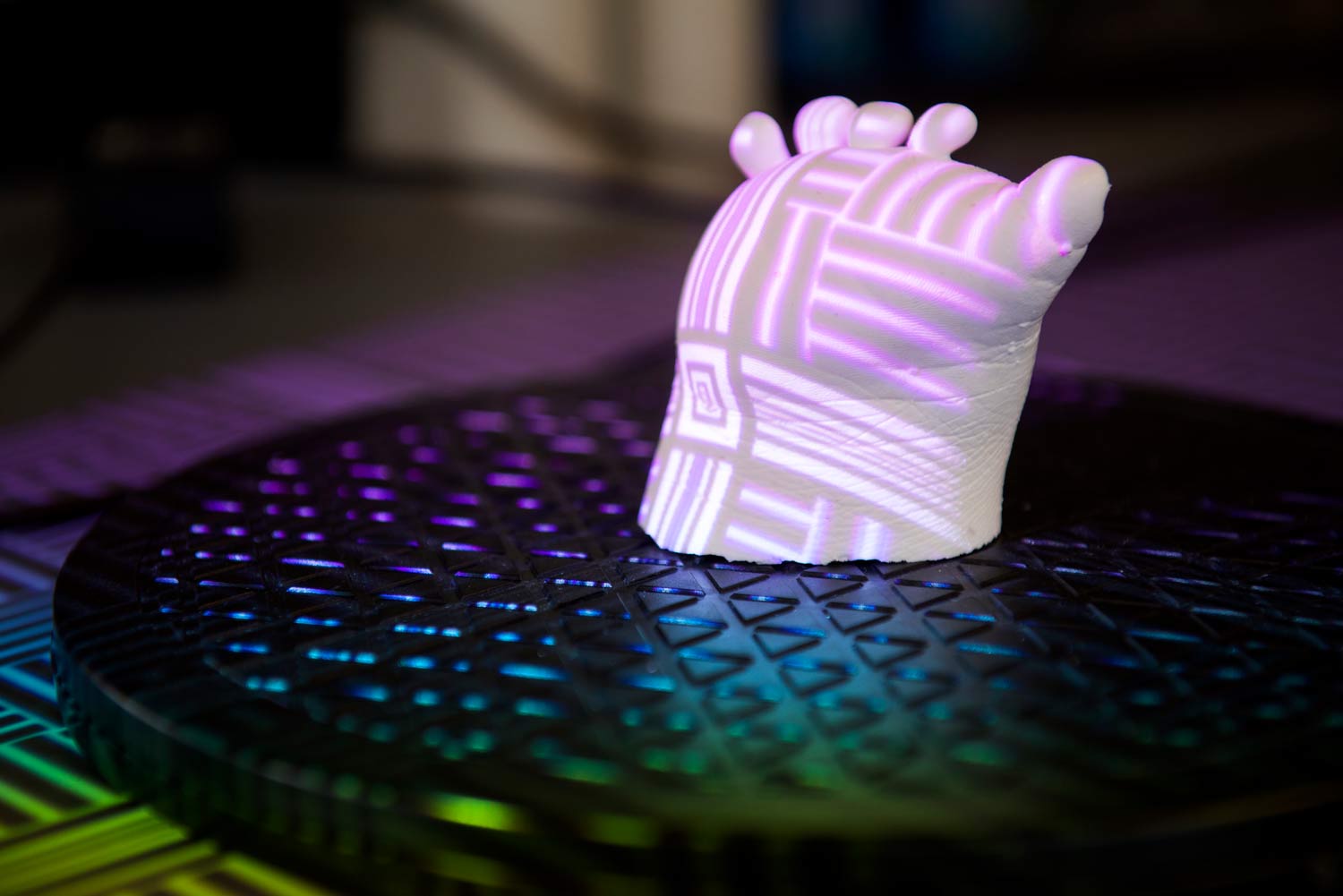

Featured image shows Yuxin Tong tweaking the prosthetic. Image Via Linda Hazelwood.