Gelatinous, 3D printed honeycombs and rooks are more resilient than they appear in recent materials research from Virginia Tech.

The project has 3D printed, “the highest temperature polymer that has ever been printed before.”

The complex 3D geometries are made from Kapton, a material also used for insulation or often on the build platform of 3D printers. In the space industry Kapton is most recognisable in sheet form, wrapped around rocket engines to provide thermal insulation in the vacuum of space.

Unwrapping the film from its sheet form demonstrates an ability to “process the nonprocessable” and 3D print the highest temperature polymer to date.

Printing the unprintable from VT ME on Vimeo.

Bullet proof

Kapton is an aromatic polyamide (aramid) – a class of high-strength and heat resistant synthetic fibers, including Kevlar which is used to make bulletproof vests.

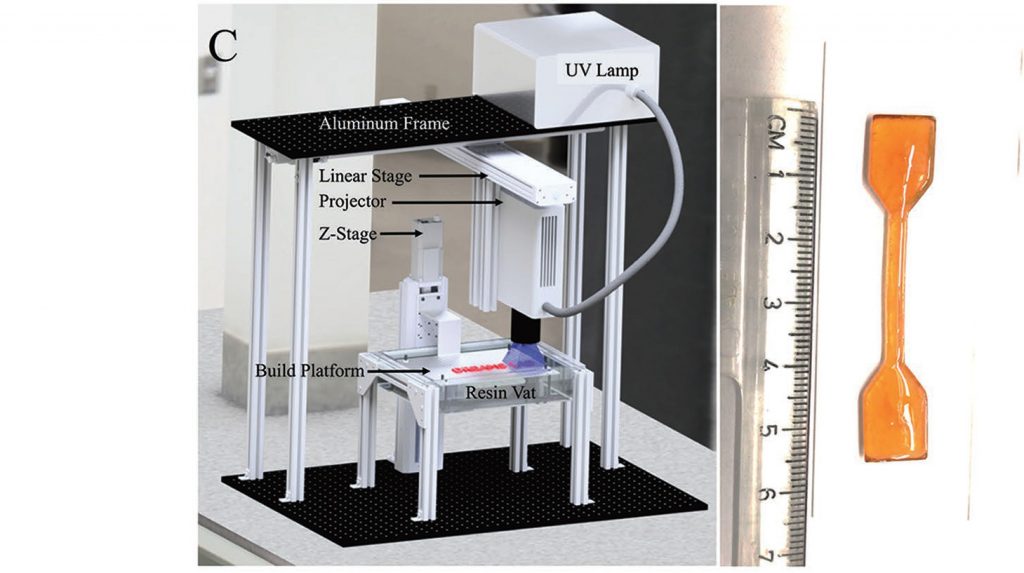

The Virginia Tech Kapton composition is 3D printed using a method of mask-projection micro-stereolithography (projecting from above) as opposed to constrained surface stereolithography (projecting from below).

With this method, the researchers are able to reach a resolution within the tens, rather than hundreds, of microns.

Printing the highest temperature polymer ever

A study, published in the journal Advanced Materials, shows that Virginia Tech’s 3D Kapton can reach 1,020°F (548.8 °C) before it starts to degrade and lose its mechanical properties.

Christopher Williams, associate professor at Virginia Tech and leader of the Design, Research, and Education for Additive Manufacturing Systems (DREAMS) Laboratory, explains, “We are now able to print the highest temperature polymer ever – about 285 degrees Fahrenheit higher in deflection temperature than any other existing printable polymer.”

Williams asserts that the 3D printed equivalent also has a comparable strength to conventionally processed Kapton film.

A material with impact

Timothy Long, a professor with the Department of Chemistry who initially worked alongside Williams on the study comments, “We chose a fairly ubiquitous high-temperature and high-strength polymer because we wanted to enable a rapid impact on existing technologies.”

Long adds that the team have already received some commercial interest in the material, and have filed a patent for its protection.

Williams adds, “Now that we can 3-D print these materials, we can start designing and printing them into much more complex 3-D shapes, which allows us to take advantage of their excellent properties over a much broader range of applications.”

2D to 3D

Graphene is another typically 2D material seeking enhanced applications via 3D printing. So far researchers have developed a number of techniques working with the material in its oxide form, but it remains a challenge to produce 3D graphene at volume.

Learn more about 3D materials, software and hardware developments in our free newsletter, on Facebook and on Twitter.

Check out the latest 3D printing events here.

Featured image: lattices and a rook 3D printed at Virginia Tech using mask-projection

micro-stereolithography. Image via Advanced Materials