A new, 3D printable smart material developed at the University of Nottingham in the UK has presented researchers with a novel way of storing, and hiding, information.

Laden with photochromic particles, the material changes color in reaction light, then turns back again when exposed to air.

“In theory,” explains project co-lead Dr. Graham Newton, “it would be possible to reversibly encode something quite complex like a QR code or a barcode [in these 3D printed parts], and then wipe the material clean, almost like cleaning a whiteboard with an eraser.”

But color changing abilities is just the tip of the iceberg.

Chameleon 3D printing

Photochromic materials have been explored before using 3D printing, producing the color-changing “mood ring” from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL).

In this application different colored photochromic inks were 3D printed using inkjet technology, unlocking potential for future consumer goods.

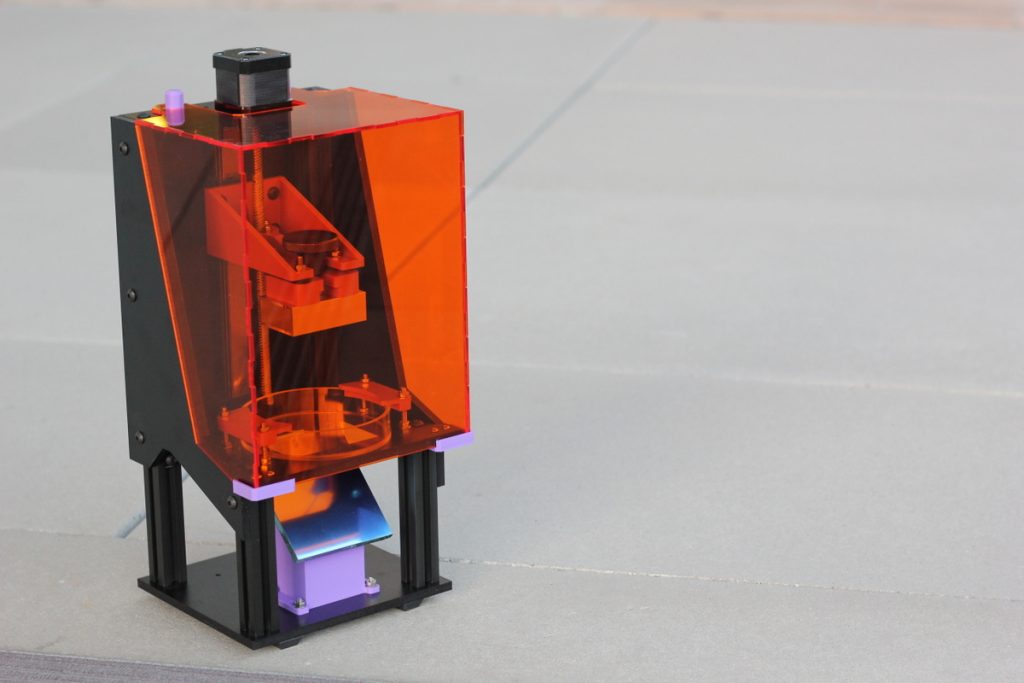

However, in the University of Nottingham research, photochromic particles are added to a light-curable material for use in a digital light processing (DLP) 3D printer.

DLP 3D printers are generally more affordable in comparison to inkjet 3D printers, especially if using a desktop machine.

In Nottingham’s case, a LittleRP open DLP 3D printer was used for the study. Excluding the light source (provided by the user) the LittleRP retails at approximately $599 for a kit.

DLP 3D printing

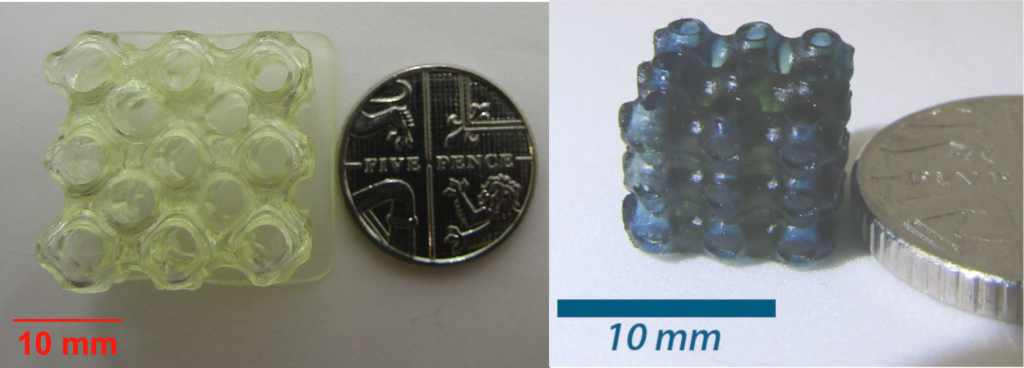

As a test experiment, Nottingham researchers chose to 3D print a gyroid cube structure.

Before 3D printing, photochromic particles were stirred into the material for 30 minutes in a dark room at around 20°C.

Each layer of the cube was then cured for 8 seconds until a solid, yellow-green product was formed. After washing this was dried overnight in dark room.

When dried, this cube this yellow cube changes color to blue under 2 mins of light exposure.

Crucially, the effect can then be reversed by returning the specimen to a dark room for 48 hours.

Real-world smart material applications

“While our devices currently operate using color changes,” explains Dr. Newton, “this approach could be used to develop materials for energy storage and electronics,” presumably by modifying the material content.

Dr. Victor Sans Sangorrin, co-lead research of the smart material project adds, “This bottom-up approach to device fabrication will push the boundaries of additive manufacturing like never before,”

“Using a unique integrated design approach, we have demonstrated functional synergy between photochromic molecules and polymers in a fully 3D-printed device,”

“Our approach expands the toolbox of advanced materials available to engineers developing devices for real-world problems.”

The paper supporting this research, “3D‐Printable Photochromic Molecular Materials for Reversible Information Storage,” is published online in Advanced Materialsjournal. It is co-authored by Dominic J. Wales, Qun Cao, Katharina Kastner, Erno Karjalainen, Graham N. Newton and Victor Sans.

Materials research and more is delivered daily in the 3D Printing Industry newsletter – sign up here. For social media updates follow 3D Printing Industry on Twitter and like us on Facebook.

If you’re looking for new professional opportunities, join 3D Printing Jobs.

Featured image shows illustration of photochromic molecules in a 3D printed cube. Image via University of Nottingham