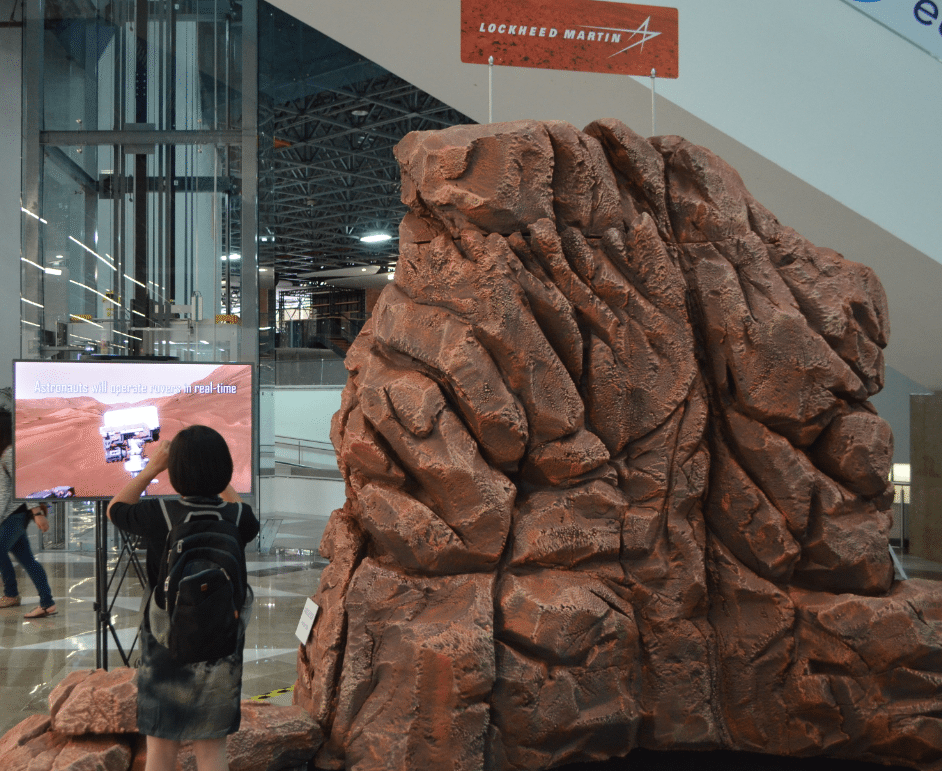

“Are we alone?” asked Lockheed Martin’s Tony Antonelli at a special event during the 67th International Astronautical Congress (IAC) yesterday. This was not a reference to the packed event hall at Guadalajara’s Expo venue, but one of three major scientific questions the U.S. aerospace and defense company hope their partnership with NASA will address: ‘where did we come from?’ and ‘where are we going?’ completing the trio.

In Lockheed’s IAC booth a case of 3D printed components sits opposite a Makerbot Replicator 2. Dave Murrow, Business Development in Civil Space tells me, “those additive manufactured parts are brackets that hold pieces of a structure together.”

That structure is Juno, the first solar-powered spacecraft built to travel to Jupiter. The 3D printed waveguide mounting support brackets were made using an Arcam Electron Beam Melting (EBM) 3D printer. Murrow says, “What we do is we print them, we polish them up and machine them to be the proper size and weight and whatnot so they fit and we put them on our spacecraft. Right now [some similar parts] are in orbit at Jupiter.”

After a five year journey NASA’s Juno spacecraft, built by Lockheed Martin, arrived in orbit around Jupiter in July earlier this year: a voyage of 1.76 billion miles. “We went into orbit proudly on July 4th, which was a big day for us” says Murrow.

Watch the Skies

This illustrates an important reason why paying attention to the aerospace industry is a useful guide to the future of 3D printing. The Jupiter mission launched in 2011 and the 3D printed parts would have been made several years before that. NASA appointed Lockheed to the Orion project just over a decade ago. So, if you want to see what is on the horizon for additive manufacturing you’d be well advised to look to the skies.

Lockheed used 3D printing to make the Juno parts for several reasons Murrow explains.

Part of our vision for manufacturing for spacecraft is to use 3D printing mostly because of being able to buy [material] stock [for 3D printing] in a wire or a powder form is much more time efficient, if you will, than buying it in big forgings.

If we want to buy a big forging, for a [fuel] tank for instance, the lead-time on that is maybe up to a year or more. By having stock for printing material in house we can cut that lead time pretty much out of our schedule and do things faster. And of course time is money, and so we wind up saving because we haven’t had to plan for quite as long.

Faster is a relative term in this industry. During their presentation on Wednesday at the IAC Lockheed’s self-proclaimed “Engi-nerds” Antonelli and Rob Chambers laid out the 12 year roadmap for a manned mission to Mars.

A Virtual Reality Within a Virtual Reality

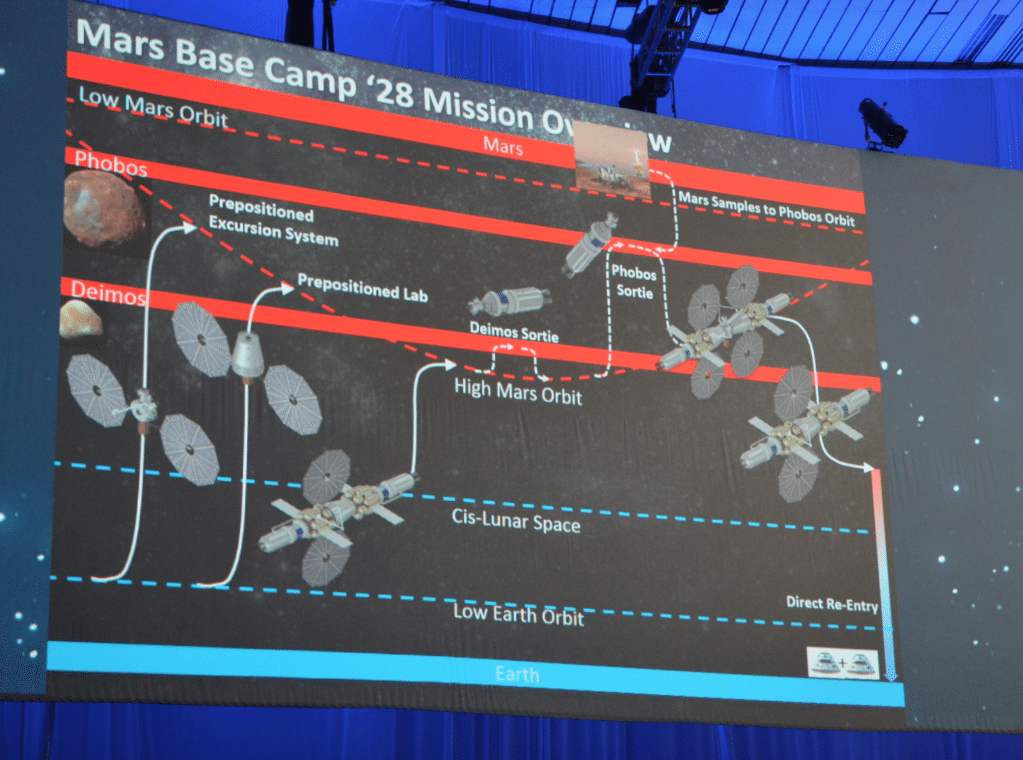

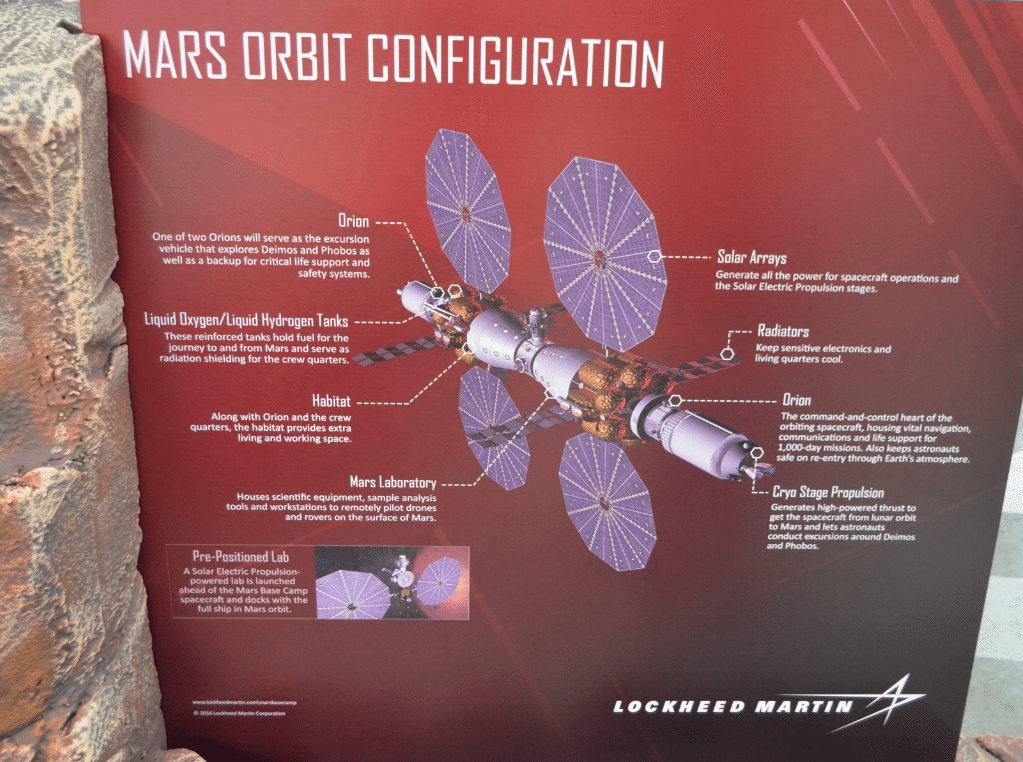

In addition to 3D printing Lockheed use many other technologies, both old and new. “Solar Electric Propulsion might sound like magic to some in the [space] community,” but Antonelli insists it is far from new. Chambers explains that “Virtual Reality is key,” to preparing for a Mars landing as Astronauts can rehearse many of the tasks they will be required to perform.

These tasks include piloting a drone, or the less charged term UAV, over the surface of the red planet and avoiding bilious plumes of methane. “Mars is alive” says Chambers and astronauts need to prepare. The VR simulation of life on Mars Base Camp even includes a mini-Inception moment where the viewer dons a second pair of VR goggles, creating a virtual reality within a virtual reality, to fly the UAV.

Lockheed use the Arcam machine to make smaller parts, but for fuel tanks and other sizeable components they use a machine from Sciaky.

Chicago based Sciaky are owned by Phillips Service Industries, Inc. a privately held company. Arcam on the other hand is currently publically traded, but the clock is ticking for the Swedish company to close on the $685 million takeover bid from General Electric, another major aeronautic company. The deal is scheduled to complete in October and has prompted speculation about the likelihood of whether GE will restrict access to Arcam’s Electron Beam Melting systems.

New Materials Revealed

“The Sciaky machine is bigger, and it’s got a feedstock in a more controlled environment,” explains Murrow.

We’ve printed titanium tanks and one of the most exciting things for us is that we’re starting to work with a different kind of titanium, a commercially pure titanium which more ductile and it may allow us to print a different kind of [fuel] tank. We’re pretty happy to be able to branch out.

Earlier in the week Elon Musk presented the SpaceX approach with vast carbon fiber fuel tanks, that also serve as the airframe of the spaceship. Smaller brackets are one thing but, “not as critical to the structure in terms of light-weighting” says Murrow. “For a big component we need to take every bit of weight out as possible.”

One of the things that we are doing right now is printing things and then doing basic material property testing on it so we can understand things like yield factors and certainly factors. [These are things] that we understand very well in Aluminum and Titanium from years of working in the space program, but with 3D printing and for the big things that are structurally critical we’re going a little slower, well because we have to.

The certification and qualification process is one barrier to the industrialization of 3D printing: capital investment is another. Lockheed paid $4 million for the Sciaky machine in 2014. Murrow adds another barrier “is just in general acceptance. In aerospace we have to be very, very careful. Mission success is the most important thing to us. So we’re not going to take any risk.”

In an interview with the manager of additive manufacturing at DARPA, a similar perspective was expressed and since 2012 the advanced research agency has worked to promote 3D printing.

So if you’ve got a material that people are unfamiliar with that adds a little bit of perceived risk or real risk. And we don’t know until we’ve flown it a few times. So there are some barriers there, I think with time we’ll get over them and some of our competitors are using 3D printing and we’re learning from their failures as well.

Mars and Back

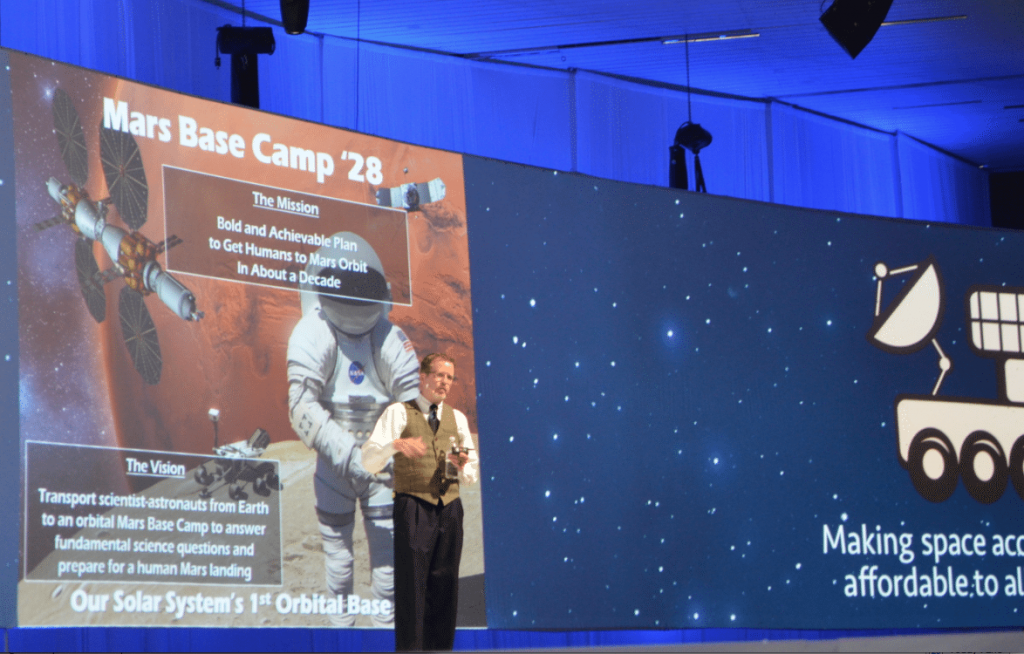

Failures are something Lockheed take very seriously. The Mars Base Camp mission craft have “two of everything, a bit like Noah’s ark” says Chambers. “You don’t get through this mission without redundant capacity” adds Antonelli. The tone is in contrast to Musk’s statement that, “the probability for death is very high” on the first SpaceX mission.

Lockheed and NASA are not expecting to find creatures roaming the surface of Mars when they arrive sometime in the late 2020’s. But, “you don’t go into a swamp to look for a fossil, you go to the Gobi desert” says Chambers.

The Mars Base Camp mission will look for life where it once might have been. And given the fact that on earth where there is water and methane -things also present on Mars- there is life, they are optimistic about the chance of an answer to some of those big questions.

All photos by Michael Petch