In recent months, a huge list of products have been announced or released, aiming to remotely or directly control desktop 3D printers. AstroPrint, the Sharebox, the Printr Element, and the MatterControl Touch are all among a new range of 3D printing accessories that provide 3D printer users a means for printing through the use of a tablet or via the cloud and without the need of a personal laptop or computer. But the ability to remotely control 3D printers is not a new one. In fact, Makers have been working on such a solution for at least a few years.

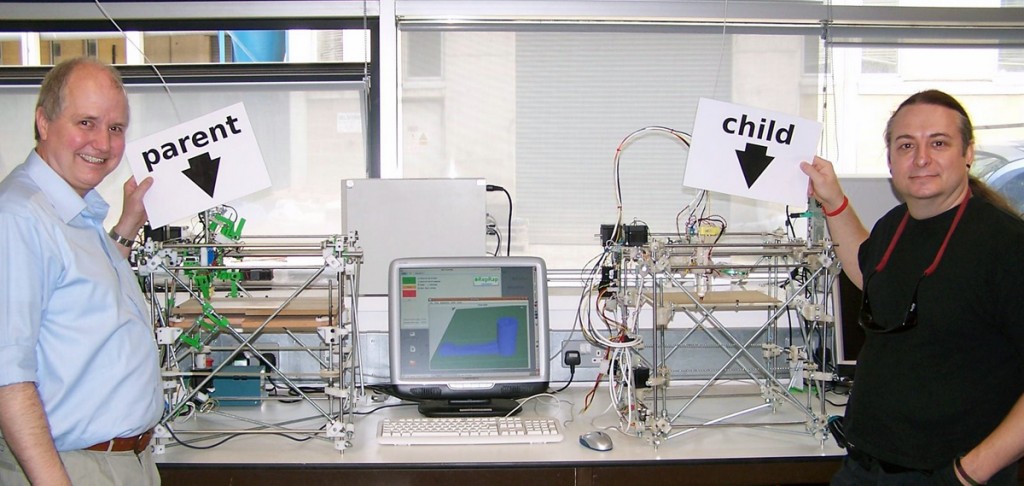

Desktop 3D printers weren’t born in the same way as many modern devices, conceived in the product design lab of a Fortune 500 company or even the garage of a Silicon Valley start-up. Simultaneously in the UK and the US, two different projects, RepRap and Fab@Home, pursued open source, low-cost 3D printing, stripping industrial FDM 3D printers down to their basic components and, with affordable electronics, assembling something that ordinary people could get their hands on without falling into debt. The RepRap movement, shooting for a 3D printer capable of replicating itself, ended up proliferating a phenomena in which Makers the world over would build their own low-cost, desktop fabricators.

Since then, a countless number of similar machines have emerged, some merely attempting to improve upon or cash in on previous iterations of RepRap 3D printers, and others setting their sights on mainstream commercial success. And, because the original generation of RepRaps were stripped of all of the bells and whistles you’d have with modern inkjet printers, laptops, even electronic kid’s toys, there are a number of features missing from desktop 3D printers to make them compatible with our 21st century lifestyle. One of the most essential is wi-fi.

As the RepRap movement was in full swing, in 2012, Makers sought to upgrade their machines to make them stand-alone and wi-fi-enabled. Among them was a German woman named Gina Häußge, who soon embarked on an open source solution to this common problem. She tells me:

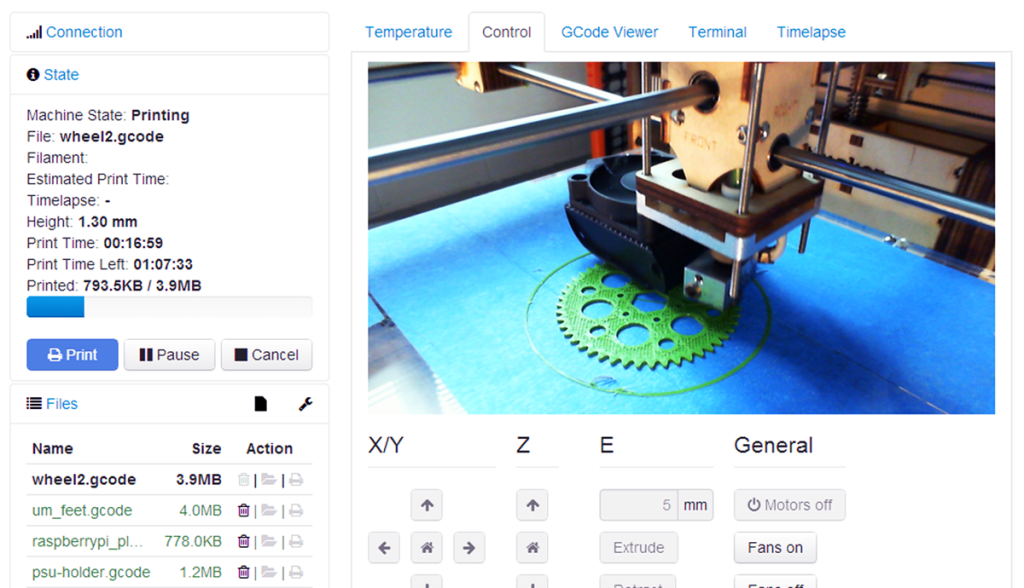

I got myself a 3D printer in 2012, looked for ways to remote control it and still get proper feedback about what it was doing and couldn’t find anything that fit those requirements. There were a couple of projects back then that did allow remote controlling the printer from within a browser (I think one was even an add-on for Pronterface), but they all lacked in the feedback department. No live monitoring, just “send stuff there and hope it does the right thing.” What I wanted though was monitoring capabilities like I was sitting right next to the printer: temperature information, webcam feed, etc. And I didn’t want to buy some expensive computer for this but I wanted this monitoring/remote control solution to run on something cheap, like a Raspberry Pi.

Over the course of Gina’s two-week Christmas vacation, she had formed the beginnings of a massive project called OctoPrint (originally called Printer WebUI, covered on 3DPI in early 2013), which was soon picked up by the open source community as a great solution for remotely controlling and monitoring prints through the OctoPrint web interface and a low-cost computer, such as a Beagle Bone or the aforementioned Pi. Add a webcam to your printer and you can even watch a print in progress.

But, soon, the popularity of OctoPrint demanded a lot more time and resources, with Gina saying, “I thought I was done but then people started using it and requesting new features and suddenly I had a full blown open source project to maintain… Maintaining and developing took more and more of my time, I also reduced to a part time contract with my employer in September 2013 – not because OctoPrint was making me any money (hah, good one) but because I felt an obligation to what I’d started there.”

While Gina continued to improve upon her passion project, at the expense of her own income and sleep, and the desktop 3D printing boom continued, new companies emerged hoping to supplement existing 3D printers, often lacking in wi-fi capabilities and remote monitoring. Similar to how the RepRap movement took off, some, like AstroPrint, built off of the OctoPrint platform, diverging into their own packaged product. Others, like the MatterControl Touch, have developed their own wholly unique solutions to bringing 3D printers up to speed with the rest of our Internet of Things.

Despite any similar roots between these new products and OctoPrint, they all seek to distinguish themselves from one another and from OctoPrint (sometimes aggressively). While companies like PrintToPeer offer free services that operate printers from the cloud via a Raspberry Pi, firms like MatterHackers sell stand-alone devices for controlling 3D printers with a tablet. Some of the advantages that these firms claim include easy-to-use interfaces or cloud printing. On the one hand, cloud computing, in general, does make processes, such as slicing and managing 3D models, faster by relying on the computing power of more powerful machines located elsewhere. And user-friendly interfaces are great for beginners that may not wish to fuss over printing specs too much. On the other hand, the cloud, as evidenced by way too many nude celebrity photos, may suffer from security issues. Lack of access to a decent wi-fi connection, too, may prevent any cloud computing from being accomplished. And, as for simple interfaces, ease of use can often translate to lack of advanced user settings.

This happens to be Gina’s view. She says, “I’m still not sold on the Apple approach to dumb everything down as much as possible, especially not at a time when the hardware is still as finicky as it is. I think letting the user decide is the better approach.” To this end, Gina is continuing to develop OctoPrint to have even greater flexibility:

I have created a full-blown plugin system that allows for extending various aspects of OctoPrint’s functionality to push OctoPrint in the direction of general adaptability to the user’s personal wishes. Want a full-fledged, all-in-one interface? Or a beginner friendly one? Or something in between? No worries; you decide. Don’t like Slicer X, but like Slicer Y? No problem; you decide which one you want to use. Want push notifications via Pushbullet or email notifications via your own account (or something else) telling you what’s happening? Just install the corresponding plugin through the plugin manager and there you have it. Your printer uses a language other than GCODE? There will also be plugin support for that in the future. Want to be able to browse YouMagine or Thingiverse or ShapeDo from within OctoPrint? Already possible, if someone writes a plugin, the necessary infrastructure is in place. This kind of flexibility is the goal, and we are getting there already; although the new ways to extend OctoPrint aren’t even fully documented yet, people from the community are already starting to contribute plugins to add or improve on various types of functionality

Gina hasn’t used the other products developed for remote 3D printer control and monitoring, seeking to preserve originality and, also, due to a lack of time. Therefore, her OctoPrint upgrades are out of a desire to improve the platform and help her community, more than they are a means of competing with other remote control systems.

But, as happened with RepRap open source licenses, some companies have taken advantage of the open source OctoPrint project. There are those remote printing solutions that have acknowledged their OctoPrint roots, as per the platform’s Affero General Public License (AGPL), while others, that should, have not.

In reference to one OctoPrint fork, she tells me, “They also contacted me, upfront about their intent to work on [their project] and promised to contribute. Well, so far I haven’t seen any code come back, but I try to not hold a grudge. It’s still a bit sad though because in the beginning, I’d hoped that we could profit a bit off each other, in regards to functionality.” The license relates only to the OctoPrint software, not the hardware, and, like most open source licenses, has pretty light requirements, in comparison to closed-source products: to provide the full source code for a piece of software (or design blueprints for a piece of hardware).

Actually, it’s a little more complicated than that. Though she’s not a lawyer, I asked Gina to elaborate on how open source licenses work. She explains, “The AGPL basically allows anyone to take source code licensed under it (such as OctoPrint), build on top of it for their own product and even sell it (commercial usage is allowed!), but with the requirement that the full source code of all the modifications and underlying base is made available under the same or compatible terms (that is the viral part of the GPL), even if the modified software is only running in the cloud and accessed by potential users via the network (and that is what distinguishes the AGPL from the GPL). Also all copyrights must be kept in place. This whole construct ensures that basically anyone can take that modified version in turn and so on and it remains free as a part of publicly available knowledge. But, when it comes to open source development, it is common courtesy to also attribute properly: if your work depends heavily on the work of some other project you just say so.”

Gina doesn’t actually think that her license has really been abused, though. She adds, “So far, I don’t have the feeling that competitors are using OctoPrint without saying so or not giving proper attribution to it. I mean, let’s be honest here, putting a web interface in front of a printer is nothing that revolutionary just because the printer happens to print in 3D.” Instead, her issues lay with the 3D printing press:

Without the (free and mostly free time) work of the open source hardware and software community, there would be no 3D printing consumer segment. There would be no hype like we have it now. All of those companies that are now shooting out of left field and trying to get a piece of the cake wouldn’t exist. And that also holds true to most of what is claimed as innovations these days by start-ups in this area. So, to sum it up: My beef is not with the companies trying to make money (at least as long as they adhere to existing licenses and don’t pull something like MakerBot did), my beef is with the current approach of reporting prominent in our industry to gobble up their Kool Aid, instead of questioning a company’s claims and comparing them to existing solutions. Journalism should ask questions, not just quote press releases.

As the Editor of 3DPI, I can tell you that Gina’s definitely right. At 3D Printing Industry, I can honestly say that we try our best to give good analysis and reporting, but we don’t always succeed. I’ve made plenty of my own mistakes in the past and I know that some of our writers have, too. In this exploding industry, and universe, we’re so rushed for time, in the haste of capitalist competition and being alive, that we can’t always give every topic our due diligence. In covering the countless number of 3D printer controls that have been released in the past year or so, we don’t always acknowledge their roots. I can’t speak for our own journalistic competitors, but I can say that many of our writers do approach developments in the industry with what I hope is a measured thinking over meaningless hype. It just doesn’t always come across.

Thankfully, the OctoPrint creator doesn’t seem to hold it against us personally. And, either way, open source pioneers like Gina will continue working, giving sites like 3DPI something to write about and a reason to exist in the first place. For OctoPrint, in particular, there are only going to be even greater news stories in the works. Due to recent support from Spanish 3D tech company bq, Gina’s able to devote her time and resources fully to her project.

bq’s support has enabled her to develop the aforementioned plugin system for OctoPrint, through which it is also made possible to regularly and semi-automatically update the platform’s software. Though this is already a part of the platform’s public development, it will also be included in OctoPrint’s next big release. She adds, “On top of that there’s also some exciting developments happening in the background I’m not yet able to talk about.” Keeping in touch with the bq team via videochat and the occasional flight to Madrid, Gina can work on OctoPrint without worrying about fitting it into her regular life and finances.