Today is the official anniversary of RepRap. At 3D Printing Industry we are marking the occasion in a series of interviews with those closely linked to the project. If you’ve used a desktop FFF 3D printer the chances are that the RepRap project has influenced the design of the hardware or software.

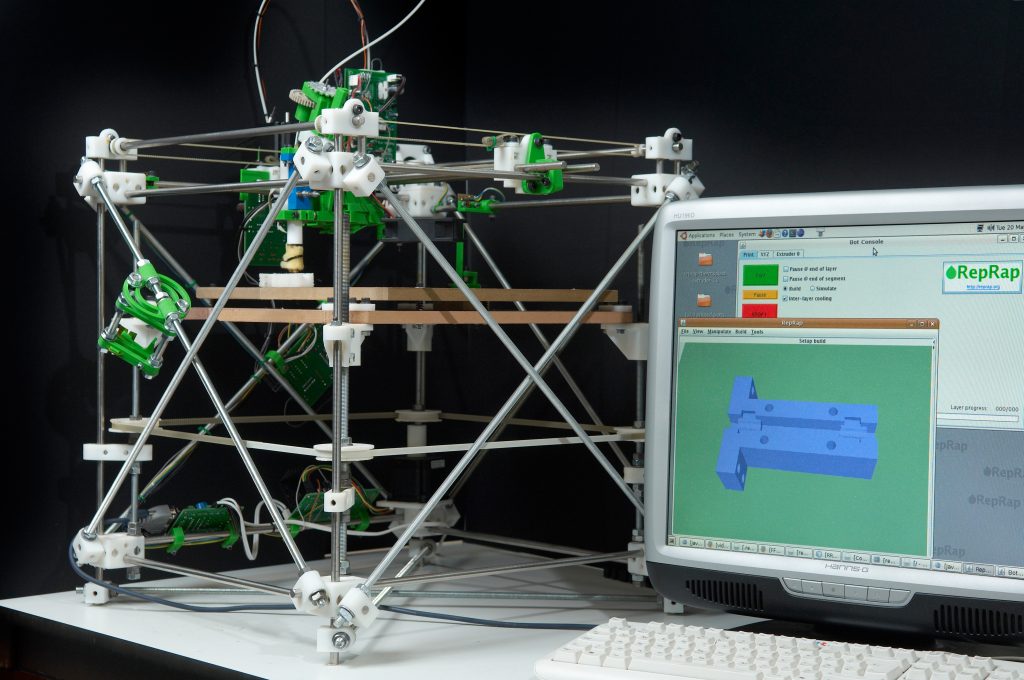

“On 29th May 2008 at 14:00 UTC Vik Olliver, Ed Sells and Adrian Bowyer assembled the very first child RepRap from a parent which was made by a proprietary 3D printer.” – RepRap website.

I asked Dr. Adrian Bowyer a few questions about the origins of the RepRap project, the need for open source in 3D printing and what’s next for the industry.

Michael Petch: So when is the official anniversary of RepRap? May 29th – I’ve seen a few celebrations already?

Dr. Adrian Bowyer: I had the idea for RepRap in 2004, and it first appeared publicly on Bath University’s website in the February of that year. The 10th anniversary this year is the important one though – it’s the anniversary of the first RepRap making another RepRap: as close as a machine can come to giving birth and so having a birthday.

As it is a special anniversary we thought we’d trail it with a few events and social media posts leading up to it.

Michael Petch: How did the idea for what would become the RepRap project come to you?

Dr. Adrian Bowyer: I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of an artificial self-replicating machine. That goes right back to childhood. In retrospect it seems it was triggered by my learning of Lionel Penrose’s self-replicator made from simple wooden cut-outs when I was seven or eight, but retrospect has poor accuracy – that may well be a false memory. And later, as an adult engineer, I always had a deep interest in biology. At base, biology is the study of things that copy themselves. But my academic research at Bath University was focussed on the mathematical and computational techniques needed to represent complicated shapes in computer-aided design systems.

Then, around the turn of the century, the British Government gave my university a large equipment grant, and the university gave some of it to me to spend. I bought two 3D printing machines – a Stratasys Dimension FDM machine and a 3D Systems Vanguard SLS machine. For the first time in my life I could hack something together in the CAD system on the computer in front of me, and have it in my hands an hour later.

This was a complete liberation. I had known about 3D printing since its first public appearance, which was as a joke by the late David Jones writing as Daedalus in the New Scientist on 3 October 1974. But knowing about something and actually using it are different, of course.

Humanity had finally, I decided, created a manufacturing technology sufficiently versatile and competent to stand a chance of copying itself.

Michael Petch: Can you tell me about the early days of the project?

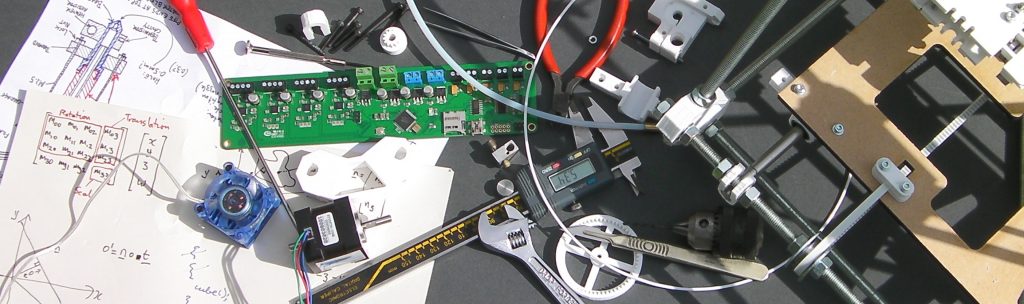

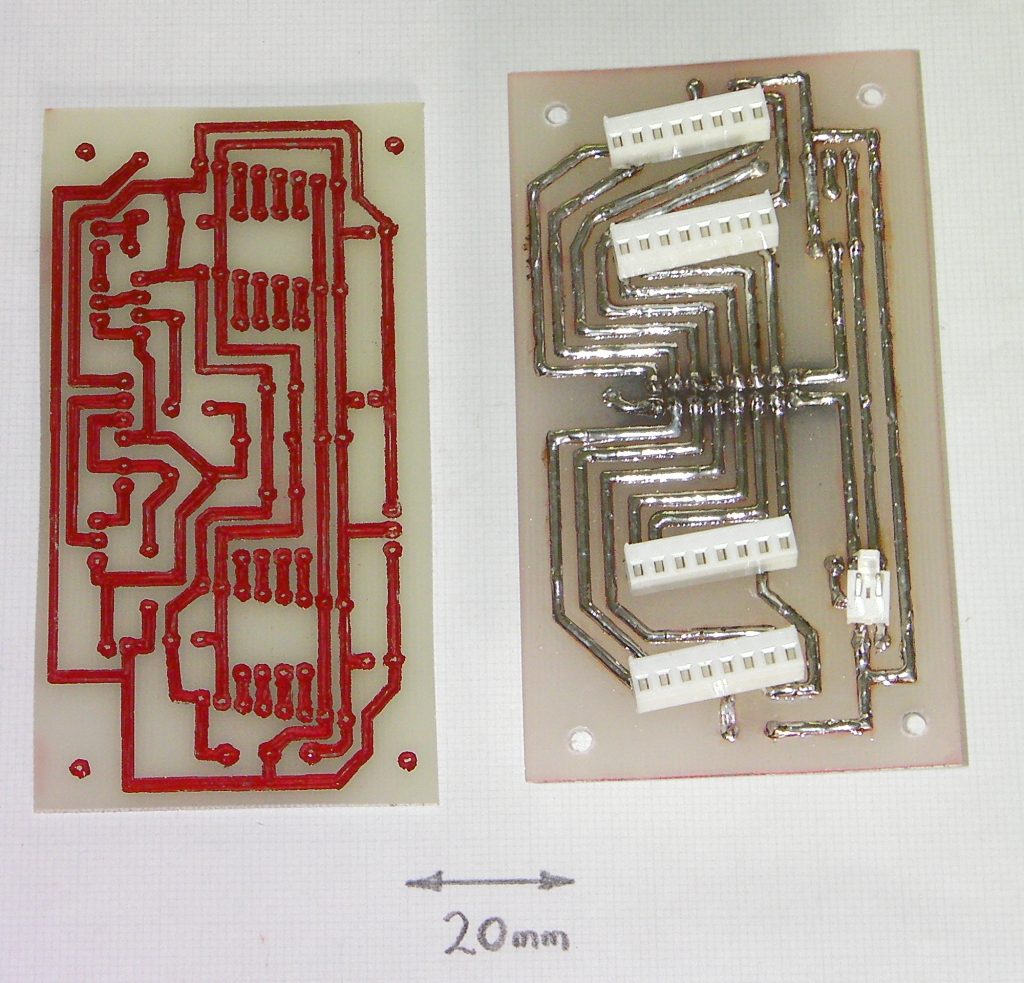

Dr. Adrian Bowyer: It started with me and my student, Ed Sells. He did his final-year project on making 3D-printed electrical circuits by having the Stratasys leave channels in prints that were subsequently filled with Field’s metal. This was based on John Sargrove’s brilliant work (nothing to do with 3D printing) just after World War II. We thought that 3D-printing circuitry was going to be important for RepRap.

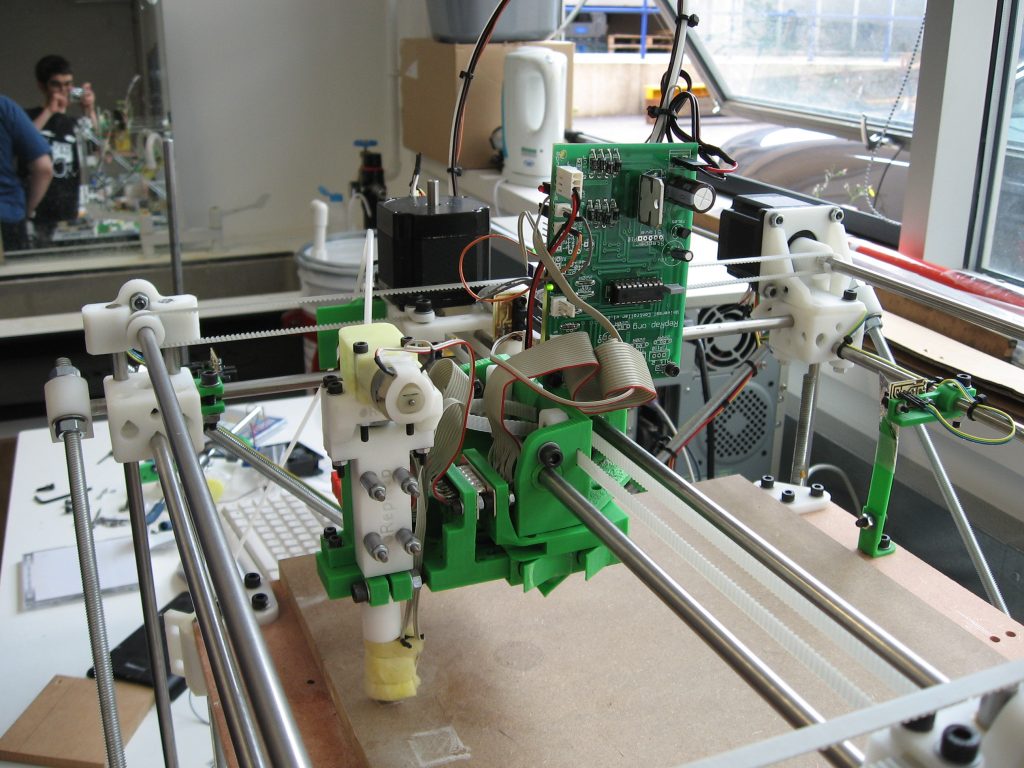

A year later Ed started his PhD on the design of the whole RepRap machine. The first was called Darwin (The Origin Of The Species…). During that year I had decided to make everything about the project open-source. My first reason for that was that I thought a general-purpose self-replicating manufacturing machine was a potential industrial disruptor, and that – in order to prevent its leading to an increase in wealth inequality – I ought to give it to everyone.

A few minutes after that (uncharacteristically noble) thought I realised it had to be open-source anyway: if you protect the IP in a self-replicating machine you are saying to the World, “I want to spend the rest of my life in court trying to stop people doing with my machine the one thing it was intended to do.” I realised I had better things to occupy my time.

Bath University were fine with my open-sourcing RepRap, incidentally, though the Chief Of IP looked at me a little wistfully when I said I was going to. A proper aspect of academic freedom is that individual academics get complete control over how their work is published, and giving all the RepRap files away was simply me publishing my results.

Given that I thought that the project might turn into something significant, I also considered I had an obligation to tell the World about it, so I got the University’s Press Office to put out a RepRap press release. This was picked up by some high-profile outlets like The Guardian, the New York Times, the Hindustan Times, the BBC, and The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. As a consequence of that, and because people liked the open-source nature of RepRap, lots of people e-mailed me volunteering to work on the project. It was as a result of all their work that RepRap was such a success.

I used to boast that I was running the World’s biggest university research project in terms of staff numbers.

Michael Petch: What were some of the early hurdles & breakthroughs?

Dr. Adrian Bowyer: I would love to be able to say that we fought against obstacles like existing-industry opposition and public cynicism; people delight in a narrative of a struggle against giants. But to be honest there weren’t hurdles, nor was there any opposition.

Not everything we tried worked, of course. But Ed, the dozens of volunteers, and I were never stuck – there was always an alternative idea, physical principle, or software solution from those

volunteers whenever a designed part of of RepRap failed to function.

A random selection of the early breakthroughs were these:

Vik Olliver (the very first RepRap volunteer) had the idea of using PLA in the FFF process – he was the first to propose this anywhere. It turned out to be a near-perfect plastic for 3D printing: you could print it on a cold surface and it wouldn’t warp and the layers welded to each other really strongly. The success of RepRap was in every way founded on the mechanical toughness of PLA-printed parts.

I myself thought of the software idea of driving of a 3D printer using a multi-dimensional algorithm: a digital differential analyzer (DDA) that considered filament movement to be just another axis of the machine like X, Y and Z. I realised immediately that this extended trivially to multiple filaments and would allow such things as proportional mixing, as well as allowing the dynamics of the machine to be easily accommodated by accelerating and decelerating its masses, with the filament extrusion automatically doing the right thing because of the four-or-more dimensional DDA. This entailed no extra computational effort.

Chris Palmer had the idea of using a simple resistor to heat the extrusion head of the machine, and he realised the need for a short melt zone achieved by both heating and cooling with a heat insulator forming part of the nozzle. He and Erik de Bruijn also had the idea of reversing the filament at the end of sections of print to produce a much better finish (though commercial systems may already have done that at the time; they were proprietary so we didn’t know).

One of the great things about the open-source nature of RepRap was that there were no secrets at all. As soon as anyone had a breakthrough idea, no matter how crazy, it went straight on the blog.

This had two marvellous results. First, it prevented any of those ideas being patented as it established prior art; and second, the ideas sparked other ideas in a spectacular firework display of creativity.

Michael Petch: When did you realise that you were onto something big?

Dr. Adrian Bowyer: I realised we were on to something big when Josef Prusa made his greatly simplified version of Ed’s design for RepRap II (which we called Mendel). Here was a bloke that I had never heard of who was having his RepRap print more RepRaps for people, and those people were falling over each other to get hold of them. I realised that the project was no longer just an interesting academic research exercise (albeit a global one), and was now out in the World and completely out of my – or anyone else’s – control.

(On “Mendel”, incidentally: all the RepRaps I get to name I name after dead biologists. As I said, biology is the study of things that copy themselves.)

Michael Petch: What has surprised you about how the project has developed?

Dr. Adrian Bowyer: At the start I thought that the project would either sink without trace or explode globally. This is back to biology again – self-replicators either go extinct or grow in numbers exponentially; there are no half measures. In the absence of data I assigned a prior probability to each of those outcomes of 0.5. Despite that sober, quantitative and dispassionate reasoning, I must allow that there is another part of me that is still flabbergasted that it did explode globally. That’s human illogicallity for you.

Michael Petch: Some early fuss and misunderstanding around 3D printing came from people, including politicians who believed 3D printers would be used for all manner of nefarious purposes, I think you may have said in the past that people tend to build more ambulances than tanks with the internal combustion engine to illustrate the point that technology is rarely intrinsically evil. Is this stage [i.e.misconceptions/fear] of 3D printing behind the industry now? What are some of the wilder misunderstandings you’ve heard?

Dr. Adrian Bowyer: There was a lot of fuss about the 3D-printed gun when it came out (it was a useless gun, incidentally; perhaps that’s the best kind…). This even made it into an episode of the TV series The Good Wife.

There has been less fuss (though gratifyingly there has been some) about Open Bionics’ 3D printed bionic limb replacements for amputees. A 3-D printed hand that allows its owner to catch a ball in flight while controlling the hand with their own nerves is really quite something. Those two examples are further echoes of my tanks-and-ambulances argument that you mentioned.

The irrational disparity in fuss over bad versus good is not a 3D-printing nor a RepRap phenomenon, but one of journalism (sorry) in general. We have evolved to pay more attention to bad news than good: if you are hungry and there is a tiger in the shade of the mango tree, it is more important for your potential future children that you fear the tiger than that you desire the mangos. But that evolved priority doesn’t work in a world that humans almost completely control and dominate -it makes us unnecessarily fearful and cautious.

Michael Petch: What are your thoughts about the state of open source in 2018?

Dr. Adrian Bowyer: I’ve already mentioned Josef Prusa. Prusa Research ships more 3D Printers than any other company, I understand. And they are all open-source RepRaps. Lulzbot are another open-source 3D printer company based on RepRap technology, and there are more. I also mentioned Open Bionics and their 3D printed hand prostheses. As implied by the name of the company, they are open-source too.

In short, I think open-source is going from strength to strength.

Michael Petch: What are you working on at the moment?

Dr. Adrian Bowyer: I’m working on a new RepRap Delta design called Lorenz (well, it would be new if I could find more time to get on with it quicker). In fact this is another wonderful example of open-source: I put the part-finished Lorenz designs up on Github, and other people got them working before me and set up a Facebook group for them…

My daughter Sally is developing a 3D-printed robot incorporating some of the technology that’s used in self-driving cars. It’s 200 millimetres across and battery powered, so it can’t run you over.

She intends it to be a teaching project in schools – pupils will be able to print it, assemble it, then experiment with writing machine-learning self-driving control algorithms. She’s doing the initial software and mechanical design, and I’m doing the electronics. We have a placement student coming shortly to work on that too. It’ll be open-source, of course.

In the background I’m developing a small 3D-printed horticultural robot to tend a patch of ground for gardeners. It’ll weed, water, get rid of slugs and encourage the plants the gardener wants. It may even till the soil and plant seeds. But it’s not nearly finished.

Michael Petch: What is 3D printing currently missing, what would you like to see

Dr. Adrian Bowyer: I think the machines are running ahead of the software to drive them. In particular, multi-material machines need better CAD to support them, specially to integrate electronic schematic design and fully three dimensional circuitry seamlessly and intuitively.

This is not a new phenomenon for automated manufacturing machines: there are shapes that 5-axis milling machines could make that are impossible for the software driving the machines to plan tool paths for. That is not the case with single-material 3D printing. It and its driving software are only constrained by the physics of the machine itself; it can be instructed to make anything that it is capable of making. This is one of the reasons 3D printing is our most powerful manufacturing technology so far. And we can do multi-materials with the same versatility, but not easily enough for the designers.

But what I’d really like to see is a £500 open-source RepRap that can work easily and reliably with electronics, plastics, metals and ceramics all in one print…

The 10th Anniversary of RepRap

3D Printing Industry will be sharing more interviews with those involved in the early days of RepRap and also with the companies who continue to apply the open source ethos to their work.

Make sure you subscribe to the 3D Printing Industry newsletter and follow us on social media if you don’t want to miss these articles.

Featured image shows Adrian Bowyer toasts the success of the first Darwin RepRap 3D printer with a 3D printed shot glass. Photo via Adrian Bowyer