Alice Martin is a conceptual artist interested in the way objects are presented in museums. 3D printing, 3D scanning and CAD are some of the tools Martin currently uses to create her work, and the idea of “remixing” is thoroughly explored. “As a contemporary artist,” she explains, “I’m mainly interested in an idea, a thought, which I then try to convey visually.”

One of the ideas Martin explores is the material culture of museums. Taking an institution like the British Museum as an example – its collection spans approximately 8 million objects, though only 80,000 (1% of the collection) are on public display at any single time (not counting the 80,000 Rosetta Stone replicas in the museum’s gift shop). One of the ways museums are trying to open up more of their collections is by exploring digital initiatives, making images and 3D models available online for anyone to access.

Taking advantage of the open access data now available, Martin creates new works that highlight the objects in a museum’s collection that would otherwise be overlooked, or archived. She comments,

“I have the desire to re-imagine these artifacts for a new audience who maybe haven’t encountered them before.”

Ways of seeing old artifacts and 3D printing

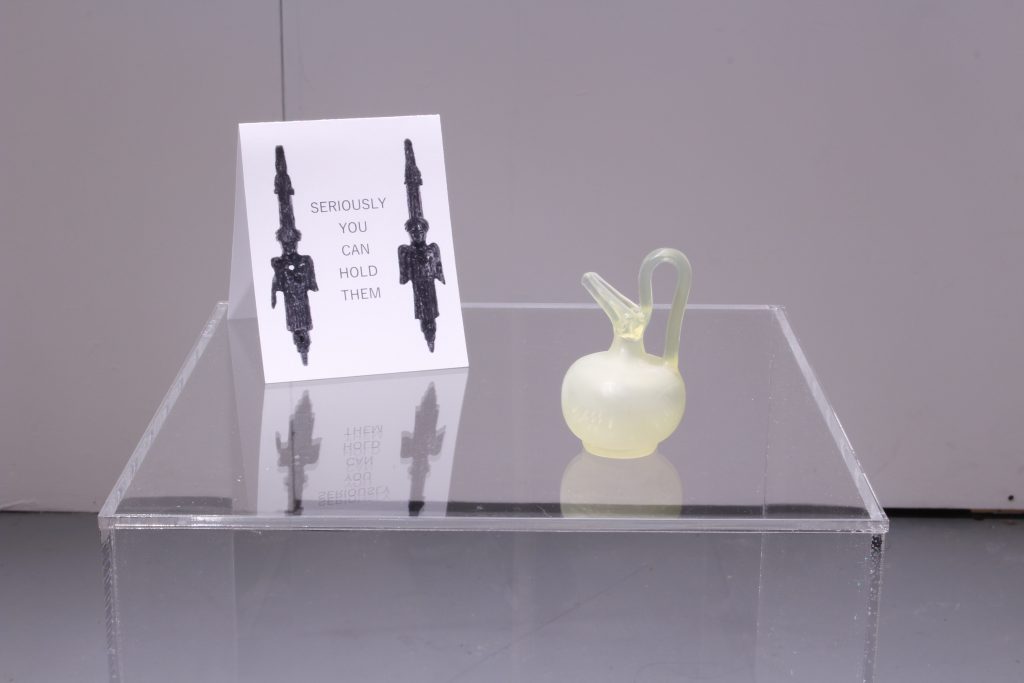

A graduate of Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen, Martin currently resides in Stirlingshire. Here, Martin is also an active member of Glasgow’s The Locale artist collective that includes exhibiting at Cass Art and The Glad Cafe. One of her most recent projects, titled Copy in Context, was hosted by GENERATOR Projects in Dundee. In this piece, Martin displays three vases 3D printed in full color sandstone, and a further three that allow visitors to pick them up and inspect them.

“With Copy on Context,” she explains, “I wanted to explore how museums share information and how open minded their approaches are, through the use of a new media.”

The object of particular focus was a Epichysis, used as a vessel in burial rites of Ancient Greece. The model for this object was sourced from the Musée Saint Raymond‘s 3D collection on Scan the World, and has been remixed by Martin to include image textures. “The purpose of projecting various images directly on to the 3D printed objects was to add an unseen context,” she explains.

Taking note of how daunting a museum experience can be, she adds, “Often at a museum, there is a piece of text to accompany an exhibit, sometimes that text can overwhelm or distract the viewer. Therefore, I wanted to replace this notion of text with images that related to the object, adding a narrative.”

One of the textures added to the vase is an image of a Terracotta funerary plaque from the The Metropolitan Museum of Art. By combining the two, Martin gives further information about the funerary practices of the time.

The three vases made to touch also ask for more active interaction from visitors. “By having a tactile engagement with my art, it makes the viewer less passive and more involved, it allows them to contemplate the work further and get up close and personal with the stuff of the past.”

It is a novel means of communication, but, as Martin adds, “I’m not pretending to be trained in museum interpretation and exhibit preparation with my work, it’s about asking questions.”

“Why can’t an artifact be presented in this way? And should it be presented in this way in the future?”

“Unlike those in a museum, I don’t have to abide by certain approaches, I can use my creative license to question the norm. Hopefully, in the end, subverting the notion of the traditional museum and replacing it with one which is less overwhelming and somewhat ambiguous. ”

What should a museum look like?

Though it can prove challenging for large, institutionalized museums and galleries to move quickly with the demands of their visitors, some smaller gallerists and household names are beginning to lead the charge.

London’s Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) recently introduced a 3D printed bust into its permanent collection to highlight the way casts are changing. The museum also recently highlighted the technology in the exhibition The Future Starts Here. In New York, Patrick Parrish Gallery embraced MIT’s Rapid Liquid Printing technology in an display of Christophe Guberan‘s light fittings, and 3D printing cropped up numerous times in Fluid Matter: Liquid and Life in Motion at MU Artspace, Eindhoven.

More 3D integration is certainly part of what Martin envisions for the future museum ideal. “A space that truly embraces 3D technologies and the sharing of information in the form of open data, [has] a lot of potential for a new type of interaction,” she said. In addition, she placed an emphasis on the necessity to display the “precious” alongside the “ordinary.” This is an idea explored further in The Museum of Dispensability, Martin’s installation for Gray’s Degree Show. In this piece, Martin created a box title Aberdeen Artefacts – a selection of ordinary, every day objects integral to the region, recreated through 3D scanning and 3D printing.

“It’s great to have precious objects such as fine metalwork as it shows how innovative people in the past were and the level of skill required to produce such items,” she says, “However maybe not everyone can relate to these types of artifacts and by having everyday items as well it sort of conveys a different narrative, representing a social history and the ordinary.”

Martin is currently working on a number of new projects that will see new exhibitions coming in 2019 and is undertaking postgraduate study at the University of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute. For all upcoming events, stay tuned to Alice Martin on Degree Art.

Is this the Most Creative Use of 3D Printing of the Year? Nominate Alice Martin and more now for the 2019 3D Printing Industry Awards.

For more unique perspectives on the 3D printing industry, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook and subscribe to our newsletter. Join 3D Printing Jobs now for opportunities in your area.