Factum Arte is a wonderful team of artists, technicians and conservationists dedicated to the documentation and preservation of items and sites of cultural significance (among other things).

On the 10th of May, a team from Factum Arte were sent to record Kala-Koreysh in Daghestan, a site of significant importance in the understanding of the spread of Islam in the region. Among the team were Alexander Peck, Ferdinand Saumarez-Smith and Eva Rosenthal as well as two photographers from Daghestan – Shamil Gadzhidadaev and Gennady Viktorov – winners of the Peri Foundation competition ‘Cultural Heritage 2.0’ and trainees at Factum (Madrid) for the month of April 2016.

Why Kala-Koreysh?

This initiative stemmed from a collaboration between Factum Foundation and the Ziyavudin Magomedov Charitable Peri Foundation to record objects of cultural significance from Kala-Koreysh using photogrammetry – a portable, adaptable and relatively cheap method for achieving high-resolution 3D data – and to produce detailed documentation of the site itself. Factum Arte hopes that the data from the project will be useful to scholars studying the Northern Caucasus, but also that it will prove equally interesting for the general public, both local and international.

This is just one of Factum Arte’s projects surrounding documentation, conservation and preservation of culturally significant sites and works.

History of the mosque and town

The mosque at Kala-Koreysh is thought to have been established by members of the Quraysh clan in the 7th century during the first outpost of Islam in the Northern Caucasus. The significance of the town extends beyond the mosque, being of importance of the Kaitag feudal state, and one in which a number of its rulers were buried.

Kala-Koreysh, ‘fortress of the Koreysh’, currently only has one resident, Bagomed. As guardian of the mosque, it is his job to receive pilgrims to the site. Kala-Koreysh stands on a small, rocky hilltop, surrounded by two rivers and beyond that, by higher hills and forests; ideal for defence but making the site almost impossible to reach, hence the population of 1. The last villagers were forcefully removed to Chechnya in the 1940s, after the resettlement of a majority of the Chechen population to Central Asia. The children and grandchildren of the last inhabitants returned to Daghestan, but, because of the difficulties created by the location, never returned to Kala-Koreysh.

What did they scan?

The team spent some time scanning the four mosque doors, which had been kept at the Museum of History and Archaeology in Makhachkala since the first half of the 20th century, although for the last three years they’ve been in storage.

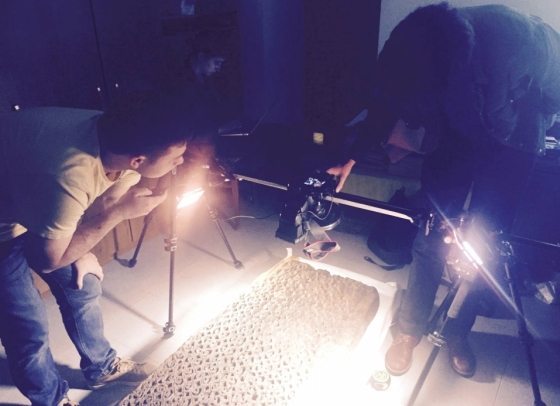

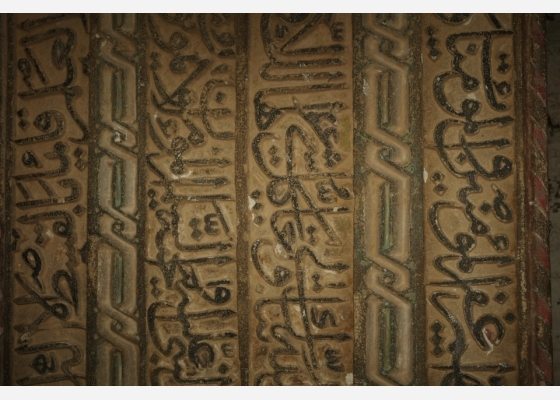

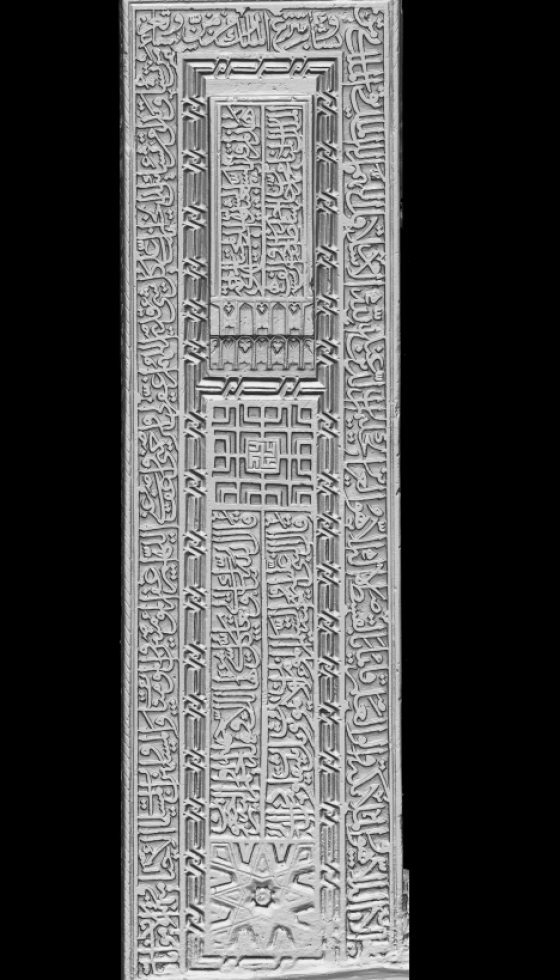

The doors are made of heavy oak with complex zoomorphic and plant motifs carved in deep relief. The first difficulty the team ran into was finding the space to scan the doors, which ended up taking place in a small storeroom. Some floor space was cleared, the doors were placed on foam mattresses for protection and they were ready to go. Several methods were attempted before deciding upon a rig system in which the camera was held on a rail supported by two tripods and photographs taken every 4 cm to achieve near 90% overlap on every photograph.

Another problem the team had to work around was that the doors’ surface was covered in a thin layer of grease. When combined with the smoothness and shine of age this proved impossible to photograph without glare. The problem was eventually resolved by reducing the reflections using a polarizing filter on the lens, and polarizing paper on the ring flash.

The team also completed a survey of the entire site, and the locations of the key graves, and of the 13th/14th century sarcophagus were mapped out on handmade plans of the graveyards, mosque and mausoleum. They found broken stones that could potentially be digitally reconstructed, but they began with the least deteriorated parts of the gravestones.

Various methods were tested to speed up the photogrammetry process and to enable systematic scanning of the lower part of the stone, including hanging the camera upside down from a rail suspended between two tripods. This method was abandoned in favor of a one-tripod system with a vertical camera-slider, and a camera with a ring-flash adapter. The ring-flash ensures that everything from the point of view of the camera is evenly illuminated, particularly important when recording a relief that is not only intricate but also bares very deep relief.

In addition to a general documentation of the site, Shamil Gadzhidadaev has been using a drone to record a high-resolution map and 3D model of the entire site. This will place the gravestones in the context of the remarkable surroundings and aid in the visualization and understanding of the rest of the data.

The team also scanned the sarcophagus, stones in the walls of the mosque and mausoleum, the interior of the mosque and mausoleum and the remaining pieces of the mihrab.

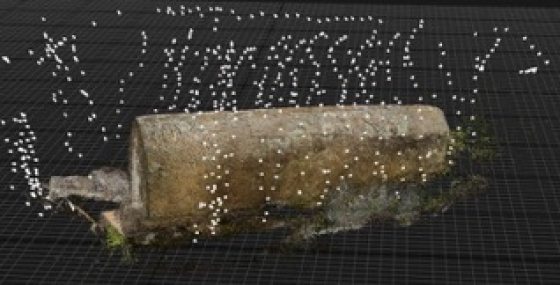

Factum Arte is focusing a great deal of its attention and research capabilities to understand the physical limitations and software capabilities involved in the application of photography as a 3D capture device. A photograph used to be an image – now it has become a map that can be accurate enough to record surfaces as well as shapes. The above image shows the sarcophagus at Kala-Koreysh recorded using photogrammetry. The software used is RealityCapture and every white dot represents the spot where every image was taken.

To find out more about Factum Arte’s 3D scanning methods, including photogrammetry, click here.